This report analyzes Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s possible electoral fortunes, given the volatility and instability in Ethiopia since his tenure began in 2018. The state is experiencing a range of crises (see map below), and the election of 2021 is occurring at a poor time for the once-popular prime minister. The outcomes for both Abiy and the Prosperity Party (PP) will be based on the sum of regional and sub-regional electoral performances. However, as this is the first election for both Abiy and the PP, there are unresolved questions about the alignment and loyalty of mid-level and local elites, on whom voting outcomes directly depend. Abiy must assess how local intermediaries and representatives can sustain their own support plus that of their beleaguered prime minister, and further whether these elites are aligned with the regime’s agendas and policies. We investigate the reach and depth of elite and public support, concentrating on the regions of Oromia and Amhara, which collectively represent over 60% of the vote share in Ethiopia. Both regions are pivotal for Abiy to carry. Abiy has engaged in different, often repressive, strategies to ensure victory.

On the one hand, the current commentary in media, policy, and academic circles outside Ethiopia suggests Abiy is on the verge of a political breakdown,1Maria Gerth-Niculescu, 2019. “Ethiopia’s ethnic violence shows Abiy’s vulnerability” DW 01.07.2019. https://p.dw.com/p/3LKcX; David Pilling and Andrea Shipani. 2020. Ethiopia crisis: ‘a political mess that makes fathers fight sons’ FT Nov 18 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/b888c23a-45ed-4937-9154-3117cc23e202 fostered by an ongoing insurgency in Tigray, a humanitarian crisis,2UNOCHA. 2021. Ethiopia- Tigray Region Humanitarian Update. 3 June 2021. https://reports.unocha.org/en/country/ethiopia/ widespread protests,3EPO Monthly: April 2021, https://epo.acleddata.com/2021/05/13/epo-monthly-april-2021/ and low popularity throughout the state4Simon Marks. Ethiopia’s PM Abiy Ahmed loses his shine. Politico EU, 25 September 2020. https://www.politico.eu/article/the-shine-comes-off-ethiopias-pm-abiy-ahmed/ as elections fast approach in late June 2021. Abiy has certainly generated political currents whose direction is unstable and unresolved,5Abel Abate Demissie and Ahmed Soliman. 2020. Unrest Threatens Ethiopia’s Transition Under Abiy Ahmed, Chatham House Expert Comment. https://www.chathamhouse.org/2020/07/unrest-threatens-ethiopias-transition-under-abiy-ahmed and created a volatile regime at the national level with six major and minor reshuffles in three years. His inner circle continues to be narrowly defined by loyalty, transactional relationships, and crisis response.

On the other hand, Abiy’s political choices are designed to restructure the regional balance of power and the political institutions of the state to secure his tenure beyond the next election. In the past 12 months, Abiy removed the greatest threats to his regime by sidelining alternative Oromo political figures and dismantling the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). He has created temporary alignment with elites in key areas and continues to dominate the political environment even where he and PP are unpopular. He is ‘the only game in town’ for the largest electoral constituency of Oromia region, and the one to bargain with in the second largest, Amhara.

The international focus on Tigray and the international reputation of the Abiy regime has distracted analysts from the domestic politics and goals of the state. Abiy’s political fortunes do not lie with the outcome of Tigray, but instead the election results in Oromia and Amhara. To secure support and success, the regime has engaged in tactics and policies including the suppression of other political contenders, widespread security operations, and a concerted attempt to co-opt or mitigate dissident elements. These have created conditions for an overwhelming Abiy victory. Abiy has openly used the power of the state, his appointment authority, and the security apparatus to enforce support, repress detractors, and promote defenders of his regime.

Yet the depth and breadth of support for the PP agenda is limited in both Oromia and Amhara, if more apparently secure in the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Region (SNNPR), Afar, and Somali regions. Many of the peripheral regions have suffered significant instability but will largely vote for PP. This election will likely provide a resounding — if hollow — win for PP that may usher in vast and destabilizing changes to the political architecture of the state.

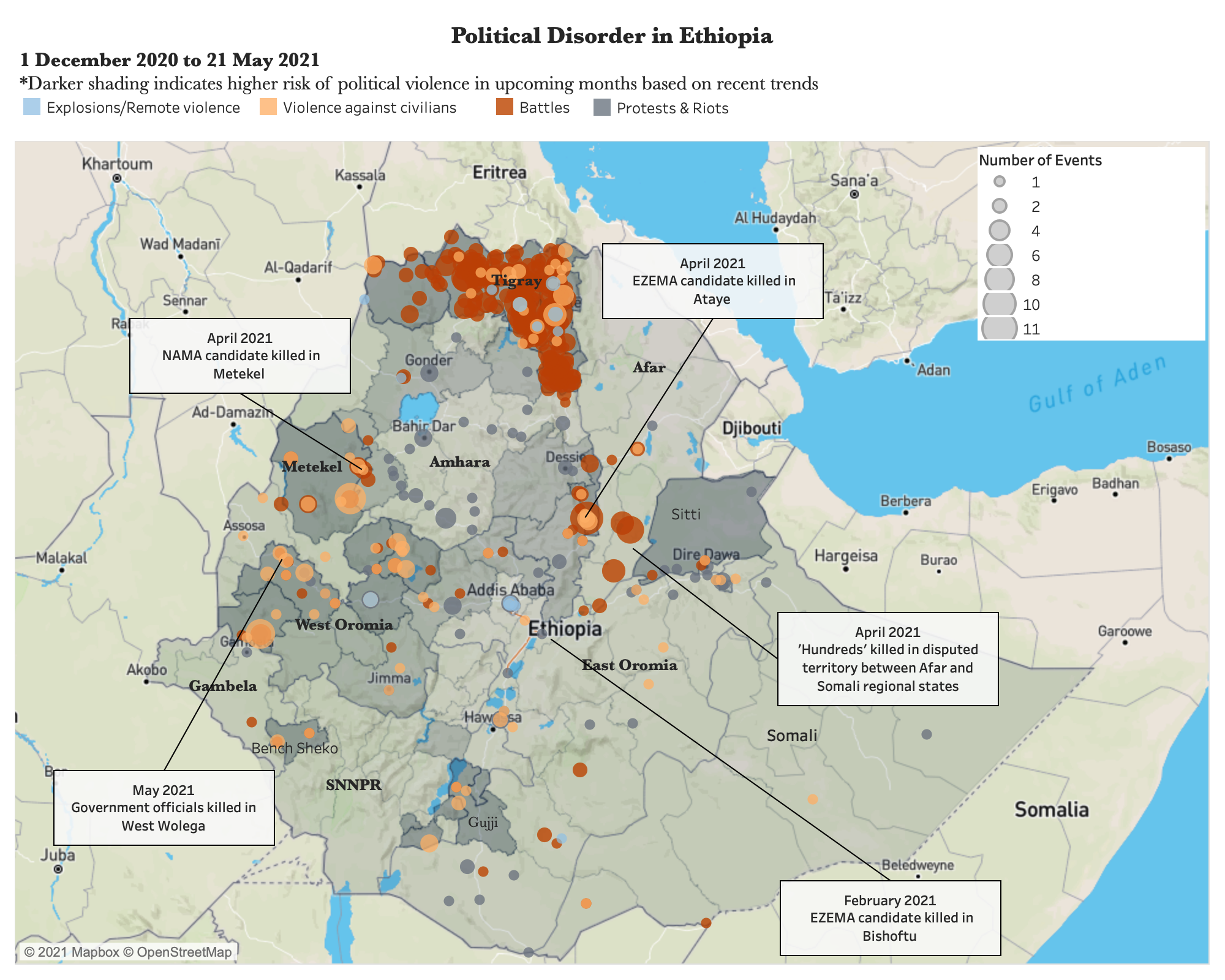

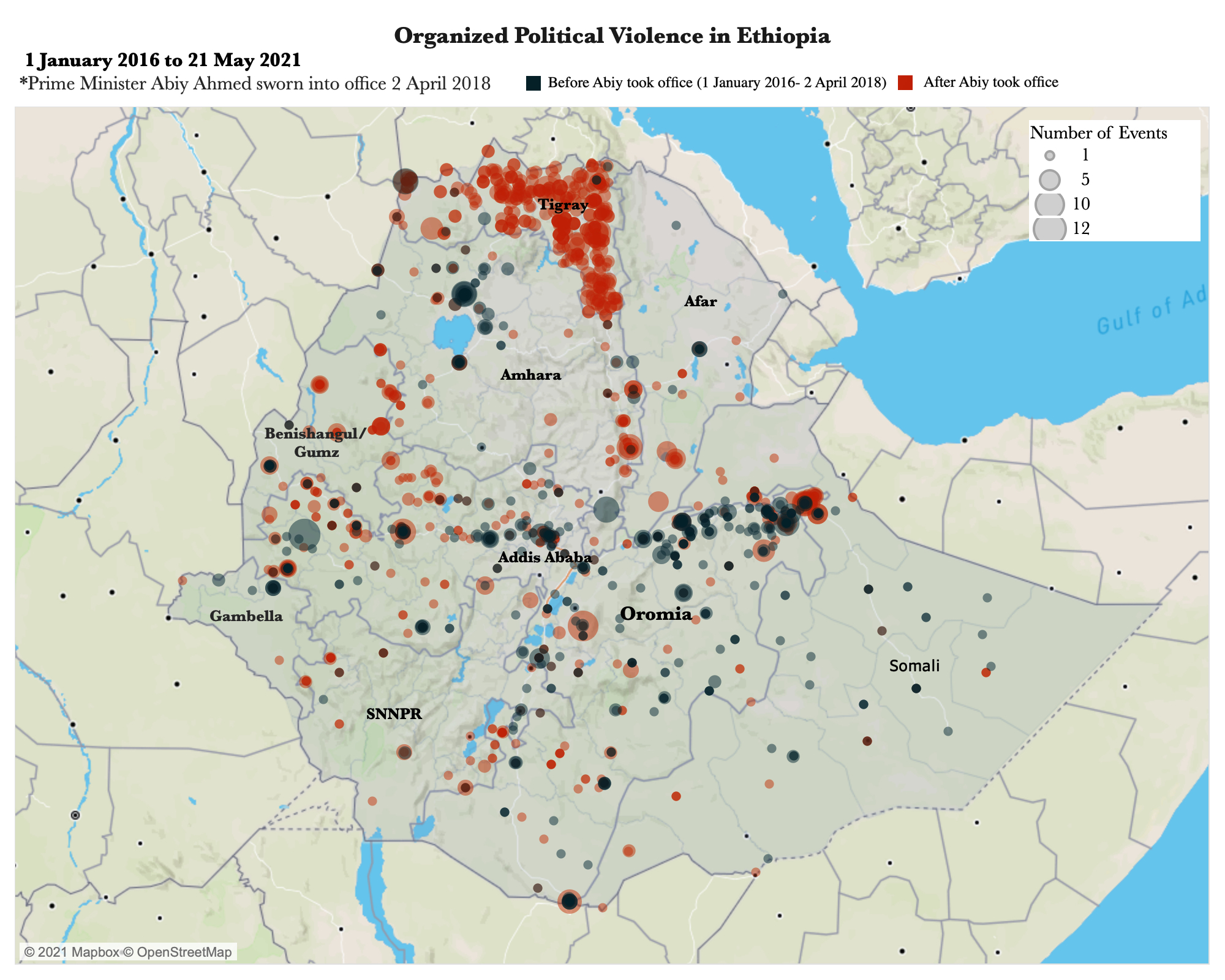

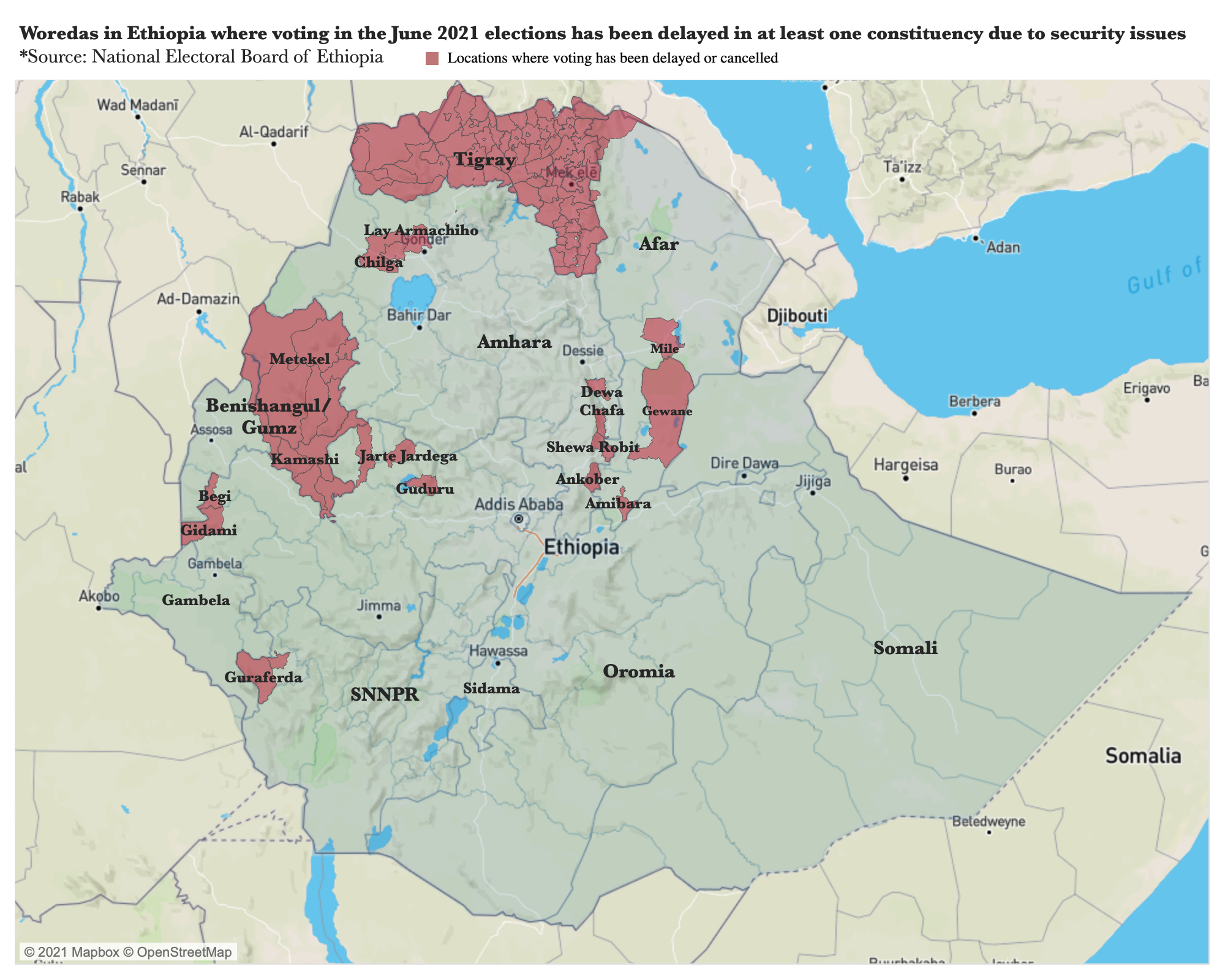

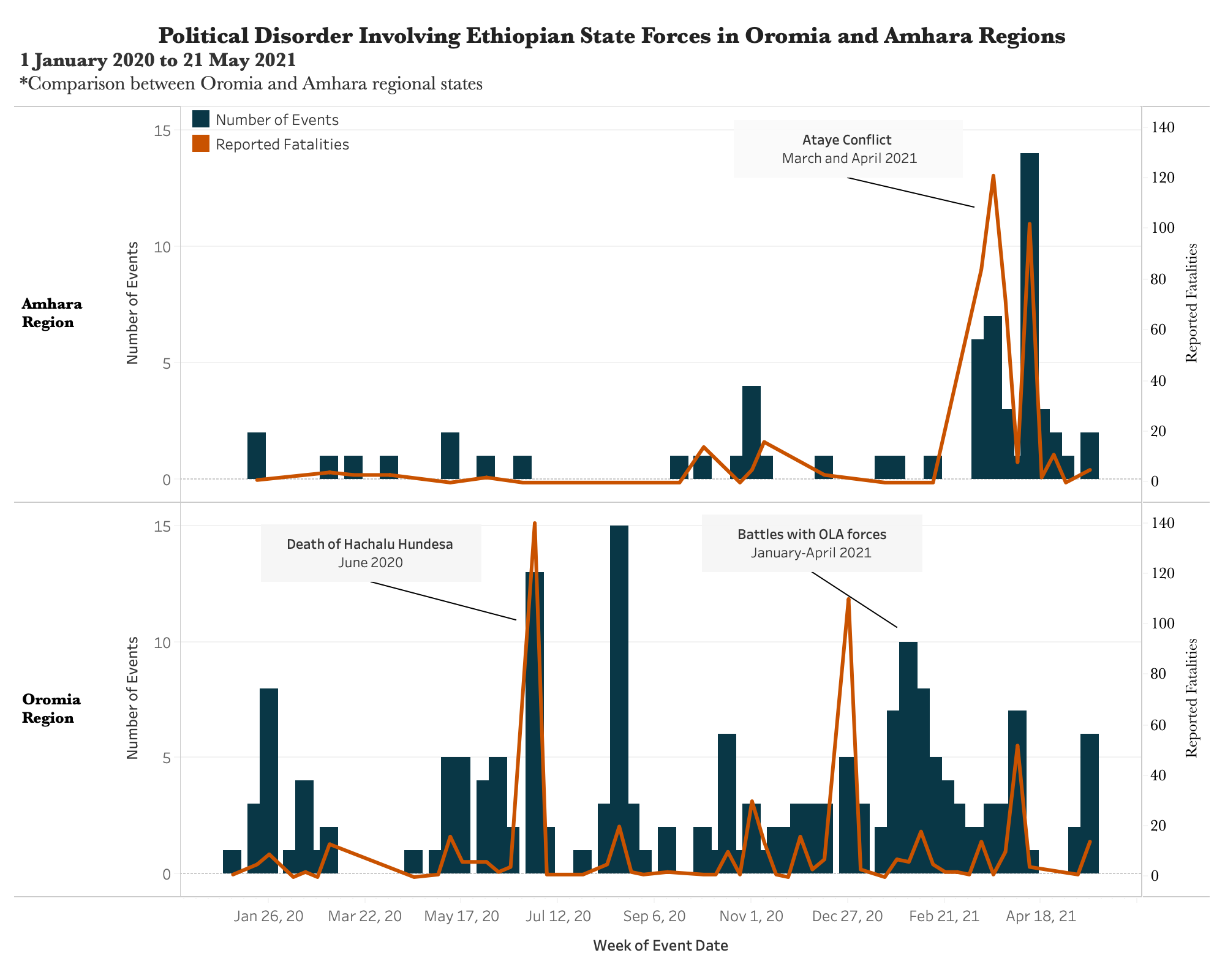

However, electoral violence will likely be minimal during the election. Rather than new ‘electoral’ violence, extremely high levels of recent political violence in the state precede and will follow the election. Suggesting a relatively violence-free election may surprise some, but when considering recent violence trends (see map below), it is clear that state violence over the past 18 months has secured Abiy’s position in that it has relegated much of the Qeerroo/Jawar Mohammed movement in Oromia,6The Qeerroo is a broad term for a social movement that is not coordinated vertically/regionally/nationally, but manifests as local movements, predominantly composed of young men (but not exclusively) who appoint one or more local coordinators (i.e. not ‘leaders’) from the local area. The participants are motivated by (a) sense of Oromo grievance about exclusions and marginalization; (b) local politics and fault lines; and (c) an engagement in redefining ‘Oromo-ness.’ These groups coalesced into a regional wide — but atomic — movement during the protests of 2014-2018,still without a leader. Jawar Mohammed, though, is closely linked to the groups. As a social movement with localized expressions, it is not an organization form that can be coordinated nationally. Yet, the Qeerroo movement is responsible for a considerable level of disorder and violence that has occurred across Oromia since 2014. and removed the TPLF as viable regional competition. This has created a repressed and relatively compliant eastern Oromia region, a violent and disenfranchised western Oromia region, a resurgent and grateful Amhara region, and a destroyed Tigray region. Post-election violence is potentially likely in Amhara, and largely depends on co-option with the National Movement of Amhara (NaMA), which is weakened after tacitly supporting disorder in the region in late April.

The real function of this election is not for political parties and candidates to compete for political power. It is to recast the loyalty and alignment of regime-subnational relations. It will lay the groundwork for a new subnational regime which will determine patronage, authority, and violence in the post-election period.

Abiy inherited a deteriorated subnational system of power from the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) regime that had ruled for 27 years and was largely controlled by the minority TPLF. One of the early hallmarks of the EPRDF system was the entrenched, widespread, top-down system of national to local control by state-party agents. That system ensured a relatively tight and restricted local political environment with strong repercussions for rebellion. Whereas national, elite inclusion was limited and narrow during the EPRDF period, Abiy broadened the political space through including ‘peripheral regions’ and overturning the hierarchy of the former system. He then required a vehicle like the PP through which the regime could co-opt and enforce its dominance in rural areas and across the country. Without the machine to secure an election outcome, Abiy cobbled together support through transactional alliances, suppression of local threats, selective co-option, and allowing particular regions relatively free rein in their internal affairs. This support will see him through this election, but will require further assessment and change after votes come in and the second stage of the Abiy regime begins.

Election Violence: Unlikely, Despite Low Executive Popularity

Ethiopia’s upcoming election is widely expected to be violent, as analysts view the current rate of violence and the grievances against the government as exceptionally high.7See Raleigh and Fuller, 2021 The central question is where violent acts will occur, and which conditions will encourage or mitigate these acts? Election violence is conflict that occurs in conjunction with an election, around candidate selection, or campaigns.8Birch S, Daxecker U, Höglund K. Electoral violence: An introduction. Journal of Peace Research. 2020;57(1):3-14. doi:10.1177/0022343319889657 It can occur before, during, and/or after an election, where the timing is dictated by the parameters of competition and expected or real outcomes. It emerges from active faultlines in the political environment. Within election violence studies, there is increasing agreement that competition, not grievance, gives rise to violence.9Wahman M, Goldring E. Pre-election violence and territorial control: Political dominance and subnational election violence in polarized African electoral systems. Journal of Peace Research. 2020;57(1):93-110. doi:10.1177/0022343319884990 It therefore follows if there is little competition, there will be low violence rates.

Public political grievances in Ethiopia are common, widespread, and now significantly ‘ethnicized.’ In recent years, grievances led to protest movements motivated by a strong, shared, and coherent sense of ethnic marginalization. However, these movements and grievances had resonance because both public grievance and elite grievance were aligned. When elites are able to capitalize on public grievances, and/or public grievances are mobilized by elites (elites using the ‘brand’ of widespread public discontent), large protest and violent movements are more likely. In short, public grievances require opportunities to generate violence, and competition to direct it. When these elements are not present, violence does not materialize as expected. As recent examples of where expected election violence did not occur because of limited incentives and opportunities, consider cases like India in 2021, the United States in 2020, and Cote D’Ivoire in 2020. Open, public grievance is present in all three, but the expected level of election violence was far less than that which occurred.

Election violence is thus likely to be over-estimated in the lead-up to the 2021 Ethiopian national elections, as analysts are more likely to expect election violence in states that are already unstable. Indeed, violence trends are on the rise across the country as conflicts widen and increase in frequency. This suggests that ongoing violence may be ‘recast’ as election violence when it occurs close to these contests, rather than the election serving as a backdrop to otherwise active political violence.

Current violence trends in the state show ongoing conflicts that are largely disconnected to the election and will likely continue to be shaped by non-election factors. In west Oromia, an active insurgency by the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) will prevent voting from taking place in many parts of the west (likely resulting in imposed representatives from PP). In the east, public and elite grievances are high, but the Qeerroo civil disobedience movement has floundered without the guidance of Jawar Mohammed, who was arrested and imprisoned in June 2020.10Ethiopia’s Oromo youth are disaffected—but also divided, co-opted, and demoralized – Ethiopia Insight. (2021, April 7). Retrieved May 20, 2021, from Ethiopia Insight website: https://www.ethiopia-insight.com/2021/04/07/ethiopias-oromo-youth-are-disaffected-but-also-divided-co-opted-and-demoralized/ Exhaustion at state repression and a lack of viable alternatives means that those who do go to the polls will neither have the motivation to engage in an anti-PP struggle, nor the choice to do so. However unorganized the Qeerroo threat is, the opposite is true of the OLA: it is entrenched in western Oromia and shows strong signs of diffusion and escalation into new areas closer to Addis Ababa and the Amhara border.

Violence occurring throughout Tigray and Benshangul/Gumuz regions has specifically been used to justify not holding the elections there, and to impose PP cadres to represent the ‘occupied’ regions. In Amhara, there is more electoral competition, as it is the sole zone with four competing ‘national’ parties (PP, Ezema, Enat, and NaMA). In turn, violence and disorder has increased in preparation for the contest, and while some conflicts are linked to party competition and grievances, other conflicts are ongoing and diffusing into new areas. A series of recent episodes does reveal how violence can be particularly important in driving more ethnicized and radical support. In Amhara’s Ataye region, attacks on ethnic Amhara have been cited as a motivator for switching votes to, or sympathizing with, NaMA (especially among the youth and those who were unsure about their support for NaMA).11See this statement by NAMA https://www.facebook.com/AMHARANATIONALISM/posts/1134457143696583

In summary, recent violence is especially high, but to attribute it to the electoral contest is wrong, as it would also be wrong to claim that the election has not accelerated specific, regional tensions. The election has heightened tensions and levels of violence in a specific way. Local elites have anticipated the threat of ethnic dominance, or — possibly worse — a dismantling of ethnic federalism. As a reaction to this coming threat, they have intensified their demands and their violence to underscore those demands. While Abiy has been seeking ‘transactional tradeoffs’ and ways to ‘de-ethnicize’ and limit ethnic ‘turns’ of dominance, political and territorial nationalism has become more radical and zero-sum.

Ethiopian Political Architecture and Geography

In determining the role of Ethiopia’s upcoming election, we expect that Abiy will have a strong victory, and that election violence will be minimal. Leaders can use information from results and performance to calculate the strength of regions and elites, develop stable coalitions, and identify, promote, and manage elites and groups.12Boix, C., & Svolik, M. (2013). The Foundations of Limited Authoritarian Government: Institutions, Commitment, and Power-Sharing in Dictatorships. The Journal of Politics, 75(2), 300-316. doi:10.1017/s002238161300002913Burchard, S. (2013). You Have to Know Where to Look in Order to Find It: Competitiveness in Botswana’s Dominant Party System. Government and Opposition, 48(1), 101-126. doi:10.1017/gov.2012.1 14Hyun Jin Choi & Clionadh Raleigh (2021) The geography of regime support and political violence, Democratization, DOI: 10.1080/13510347.2021.1901688. This paper is open access, and can be read directly from the site in full. Having elections is particularly useful for counter-balancing security elites who might threaten the regime with military tactics, test the political capabilities of rivals, and calibrate and design ground rules for political competition so that they may dominate.15Tordoff, W. and Young, R. (2005), Electoral Politics in Africa: The Experience of Zambia and Zimbabwe. Government and Opposition, 40: 403-423. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2005.00157.x 16Nam Kyu Kim & Alex M. Kroeger (2018) Do multiparty elections improve human development in autocracies?, Democratization, 25:2, 251-272, DOI: 10.1080/13510347.2017.1349108

Elections allow leaders to assess the authority and alignment of local elites, and return information about the effectiveness of local intermediaries, the utility of clientelist practices, and the coordination between national and local powers.17Magaloni, B., Diaz-Cayeros, A., & Estévez, F. (2007). Clientelism and portfolio diversification: A model of electoral investment with applications to Mexico. In H. Kitschelt & S. Wilkinson (Eds.), Patrons, Clients and Policies: Patterns of Democratic Accountability and Political Competition (pp. 182-205). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511585869.008 This is in line with practices across the continent: for leaders of ‘competitive autocracies’ or ‘violent democracies,’ internal elite consolidation and coalition building is vital,18Koter, D. (2013). King Makers: Local Leaders and Ethnic Politics in Africa. World Politics, 65(2), 187-232. doi:10.1017/S004388711300004X although gauging local support levels can be difficult.19Hyun Jin Choi & Clionadh Raleigh (2021) The geography of regime support and political violence, Democratization, DOI: 10.1080/13510347.2021.1901688

Therefore, it is in the interests of regimes to hold elections even when they know the overall results: assessing the elite for their ‘alignment’ (coordination with national regime support and agenda), ‘loyalty’ (the degree to which they have limited the reach and removed alternative contenders from their local area), and ‘leverage’ (how popular and able to generate votes is the local elite at the subnational level) is key. As election results have direct effects on the geography of regime support, the most significant changes will be at the local level, which Abiy and the PP leadership will be able to reorganize for the impending changes in alignment and PP agendas in the coming term.

Control of local authorities — whose role is to generate votes and secure patronage and positions for themselves — is central to this process of machine politics. The ruling party pays close attention to the votes received by candidates and uses them to measure their popularity and effectiveness.20Hyun Jin Choi & Clionadh Raleigh (2021) The geography of regime support and political violence, Democratization, DOI: 10.1080/13510347.2021.1901688 In this way, elections in authoritarian states function as ‘free markets,’ where a regime can measure the value of local elite effectiveness. It is also a “public, and credible, way to commit to [resource or position] allocation.”21Blaydes, L. (2010). Elections and Distributive Politics in Mubarak’s Egypt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511976469; Abdukadirov, Sherzod, The Problem of Political Calculation in Autocracies (December 1, 2010). Constitutional Political Economy, Vol. 21, No. 4, 2010, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2343935

Abiy’s most pressing issue is how to build and fortify local alignment to pursue the (somewhat vague) policies of the PP, and to engage in constitutional changes that will limit ethnic federalism. He has already altered the structures, budgets, and directives of significant federal and regional security sectors,22Addis Standard. 2020. “PM Abiy sees new leadership in entire security sector foreign ministry” from https://addisstandard.com/news-alert-unprecedented-move-by-pm-abiy-sees-new-leadership-in-entire-security-sector-foreign-ministry/; Ahmed Soliman, 2018. “Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Shows Knack for Balancing Reform and Continuity.” Chatham House Expert Comment.; Africa Confidential, “Abiy tests the military” Vol 59, no. 9. and he has upended the representation of groups and elites in both federal and regional offices.23Addisu Lashitew. 8 November 2019. Ethiopia Will Explode if It Doesn’t Move Beyond Ethnic-Based Politics. Foreign Policy https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/11/08/ethiopia-will-explode-if-abiy-ahmed-doesnt-move-beyond-ethnic-based-politics/ His original path to power required a reorganization of a central elite coalition, rather than a replacement of elites and interests.24Africa Confidential. “Abiy makes a promising start” in Vol 59, no 7. https://www.africa-confidential.com/article/id/12289/Abiy_makes_a_promising_start This has destabilized a system that was built upon “hierarchical, stratified, competitive and polarized”25Sarah Vaughan (2011) Revolutionary democratic state-building: party, state and people in the EPRDF’s Ethiopia, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 5:4, 619-640, DOI: 10.1080/17531055.2011.642520 for a discussion of the different phases through which EPRDF cultivated and built national-local structures through which to govern. P 261. ethno-regional imbalance, Tigrayan dominance, and state repression. Ethiopia’s constitution pre-determines who can participate in politics through its current provisions about territorial administrations and the ethno-political determinants of authority. Elites engage in politics through their coordinated ethnic-regional parties and positions.26ICG, 2009. ‘Ethnic Federalism and its Discontents”. Africa Report N°153 – 4 September 2009 This system creates a zero-sum game at the top whereby regional elites contest the proportion of positions and proximity to the leader. At the subnational level, the main avenue to achieving power and authority lies in the establishment of a territorial administration, which — according to the constitution — is advanced through an ethno-territorial dominance logic. The result is that Ethiopian politics became firmly entrenched in ethno-regional contestation at the national level, and ethno-territorial dominance contests at the subnational level.27ICG, 2009. ‘Ethnic Federalism and its Discontents”. Africa Report N°153 – 4 September 2009 The present system, though, has adopted many features of the former EPRDF period, while creating new winners and losers in the process.28See Sarah Vaughan (2011) Revolutionary democratic state-building: party, state and people in the EPRDF’s Ethiopia, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 5:4, 619-640, DOI: 10.1080/17531055.2011.642520 for a discussion of the different phases through which EPRDF cultivated and built national-local structures through which to govern.

On the subnational level, the EPRDF was notorious for its extensive system of control.29Further information about the structure of this system can be found in ICG’s 2009 report “Ethiopia: Ethnic Federalism and its Discontents” where on page 18, it states: “The EPRDF’s most effective instrument of local coercion is the kebele structure…. For ordinary Ethiopians, kebele officials and party cadres personify the state in their everyday life. Rural inhabitants’ welfare depends considerably on good relations with kebele officials, who oversee services. Higher-ups in the EPRDF select these officials before they are submitted to popular approval. In daily operations, kebele administrators are aided by model farmers known as “cadres,” militia known as ta taqi (gunmen in Amharic) and party members. At elections, these local officials form the backbone of the EPRDF machine.” This is further supported by footnotes within: (194): “They act as gatekeepers to a wide array of government services, as they are tasked with distributing land, food aid, agricultural inputs, registering residents, marriages, deaths and births, collecting taxes, upholding security, and arbitrating property disputes.” See also T Lyons, (1996) “Closing the Transition.” This report further notes that after the 2008 elections, kebele structures massively expanded to between 100-300 officials (cadres) who determine the distribution of food, agricultural inputs, security, and other forms of patronage, and ‘report irregularities.’ The report further states (p19) that “local party officials and ‘cadres’ are assigned to monitor the everyday activities of their immediate neighbors”, and it effectively operates as an extensive surveillance system. Citizens were patrolled by central party operatives who themselves belonged to an ethno-regional party positioned in a distorted and imbalanced hierarchy of power, largely controlled by a minority group who had effectively centralized authority from the top to the bottom of the state.30Vaughan and Tronnvoll (2003) The Culture of Power in Contemporary Ethiopian Political Life. Stockholm: Sida, 2003. These local gatekeepers for the EPRDF had access to a position, local authority, and patronage; their loyalty was assured by the lack of other political affiliation options, plus the punishment meted out for disloyalty. In kebeles across the country, these cadres were responsible for reporting on a number of households, persons, and their activities.31The number of households and persons that each cadre is responsible for differed in sources and interviews from a low of 1-3 (reportedly in Tigray by an interviewee) to 1 per 5 households (see ICG, 2009 report). Reports were coordinated in systems above the kebele, woreda, and zone levels. Containment and control were the intentions of this system. The government also used excessive violence and development aid to keep local areas compliant and controlled.32Zemelak, A. (2011), Local Governments in Ethiopia: Still an Apparatus of Control? Law, Democracy and Development, Vol.15, pp.1–27. This subnational system is how EPRDF won elections,33Merera Gudina (2011) Elections and democratization in Ethiopia, 1991–2010, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 5:4, 664-680, DOI: 10.1080/17531055.2011.642524 kept out detractors, and mostly limited internal dissension despite extremely unfair political representation and rights for groups across the state.

Challenges to this system of central dominance via local gatekeepers’ became acute after the death of Meles Zenawi, who had formulated this system and held power from 1991 until he died in 2012. After his death, this system unraveled,34Sarah Vaughan (2011) Revolutionary democratic state-building: party, state and people in the EPRDF’s Ethiopia, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 5:4, 619-640, DOI: 10.1080/17531055.2011.642520 for a discussion of the different phases through which EPRDF cultivated and built national-local structures through which to govern. and elections in 2015 reinforced how the EPRDF ‘overcorrected’ in its approach to local support for opposition candidates and its failing cadre system to force acquiescence.35Arriola, LR, & Lyons, T. (2016). The 100% election. Journal of Democracy, 27(1), 76-88. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/jod.2016.0011 Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/23h3478g The fatal blow to the EPRDF came from the local level, where a high degree of public grievance in regions lower on the political hierarchy (i.e. Oromia) culminated in a social movement that swept through the state in 2014. The EPRDF machinery at the bottom was largely decrepit, unable to contain dissension, and many thought it and its local gatekeepers corrupt. Youth movements complemented attempts by regional elites to counter the central minority-held hierarchy of power, and the resignation of Prime Minister Haile Mariam led to the eventual, and surprising, choice of Abiy Ahmed to lead the EPRDF.36Jazeera, A. (2018, April 2). Abiy Ahmed sworn in as Ethiopia’s prime minister. Retrieved May 20, 2021, from Aljazeera.com website: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/4/2/abiy-ahmed-sworn-in-as-ethiopias-prime-minister

National-level changes were swift: Abiy opened new avenues for political elites and removed TPLF elements at the highest levels37African Intelligence, 22.02.2021 Abiy purged his military high command to prepare for his war against the TPLF; African Intelligence, 05.07.2019 Behind the scenes of the army and security appointments in the armed forces and intelligence. He welcomed previous rebels and rivals back into the country.38Deutsche Welle (2018). Violence ahead of the return of Ethiopia’s Oromo Liberation Front sparks concern | DW | 14.09.2018. Retrieved May 20, 2021, from DW.COM website: https://www.dw.com/en/violence-ahead-of-the-return-of-ethiopias-oromo-liberation-front-sparks-concern/a-45494241 However, the vast ideological differences among opposition groups — from ethno-regional ‘radicals’ like the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) to ‘pan Ethiopian’/multi-ethnic parties like Ginbot 7/Balderas — signaled that there would be severe tests ahead for the integration of Ethiopian political interests.

The eventual creation of the PP came at a critical stage of political integration: once in power for over a year, national alignment and loyalty to Abiy and his vision of regional, central, and external elites and parties was becoming clear. The PP welcomed and promoted supporters, and punished elite detractors,39Lemu, Assefa (2019). A Closer Look At (Ethiopian) Prosperity Party. ECADF. including Abiy’s Oromo base and close political affiliates Lemma Mergesa (former president of the Oromo regional party) and Jawar Mohammed (a firebrand populist who considered himself the true representative of the Oromo region). With the establishment of this new party, the opposition landscape developed quickly: the TPLF refused to join, and sat in opposition as Abiy’s regime took advantage of the centralization power the TPLF had granted themselves during the previous dispensation.40AfricaNews. (2019, November 21). Tigray bloc rejects “unlawful” merger of Ethiopia ruling coalition. Retrieved May 20, 2021, from Africanews website: https://www.africanews.com/2019/11/21/tigray-bloc-rejects-unlawful-merger-of-ethiopia-ruling-coalition/ Part of the Oromo elite that had led Abiy to power coalesced into the Oromo Federal Congress (OFC),41AfricaNews. (2019, December 30). Ethiopia’s popular activist Jawar Mohammed joins opposition OFC party. Retrieved May 20, 2021, from Africanews website: https://www.africanews.com/2019/12/30/ethiopia-s-popular-activist-jawar-mohammed-joins-opposition-ofc-party/ and stood in loud defiance of his ‘power grabbing.’ The parties that had returned to the Ethiopian scene fractured; this included the OLF splinters, which led to the continuation of violence through OLF-Shane (OLA).42Zecharias Zelalem. (2021, March 20). Worsening violence in western Ethiopia forcing civilians to flee. Retrieved May 20, 2021, from Aljazeera.com website: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/3/20/worsening-violence-western-ethiopia-forcing-civilians-to-flee The Amhara political scene saw the establishment of NaMA, a populist nationalist party dedicated to promoting and securing Amhara political representation across the country.43Admin. (2018, June 11). National Movement of Amhara (Nama) party officially founded in Bahir Dar. Retrieved May 20, 2021, from Borkena Ethiopian News website: https://borkena.com/2018/06/10/national-movement-of-amhara-party-in-bahir-dar/ The youth movements that had engaged in violent local dissension in recent years — Qeerroo in Oromia region,44BBC News. (2020, July 5). Hachalu Hundessa: Ethiopia singer’s death unrest killed 166. Retrieved May 20, 2021, from BBC News website: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-53298845 Fano in Amhara region,45Admin. (2020, March 21). Ethiopia: Gondar region security incident left at least three injured. Retrieved May 20, 2021, from Borkena Ethiopian News website: https://borkena.com/2020/03/20/ethiopia-gondar-region-security-incident-left-at-least-three-injured/ Heego in Somali region46Tobias Hagmann and Mustafe Mohamed Abdi (2020, March 1). Inter-ethnic violence in Ethiopia’s Somali Regional State, 2017 – 2018. LSE Conflict Research Programme Research Memo March 2020. — began to question the new regime’s commitment to ethno-nationalism.

Where did this leave Abiy and his approach to rebuilding a new subnational machine? Abiy inherited a severely weakened local control system whose structures and elites were challenged by association with the previous regime and local dissent. Many local authorities simply acquiesced to the new regime and replaced their EPRDF cards with those from PP; their employment was secure even if their loyalty to the new center was unclear.47Interviews in Eastern and Western Oromia, 2021. The subnational power structure has not been reconstructed to any degree; this has left elite alignment and loyalty at the subnational level in flux. This system was vital for political control, and election returns that reinforced power at the center and within the party. In response to the lack of a subnational machine, the PP functions as a political ordering vehicle to manage former EPRDF bureaucrats and elites.

Across some of the more troublesome areas, including the Wollegas in west Oromia, assassinations of local authorities occurred at the hands of the OLF-Shane.48BBC Amharic. (2021, May 17). የዞን አመራርን ጨምሮ በምዕራብ ኦሮሚያ 5 ሰዎች በታጣቂዎች ተገደሉ – BBC News አማርኛ. Retrieved May 20, 2021, from BBC News አማርኛ website: https://www.bbc.com/amharic/news-57146500 The youth movements continued to challenge Abiy directly: in Oromia, the Qeerroo reasserted their close relationship with Jawar Mohammed,49Addis Standard. (2021, February 8). News: As Jawar et.al continue hunger strike Oromia region sees multiple protests demanding their release, justice for slain artist Hachalu – Addis Standard. Retrieved May 20, 2021, from Addis Standard website: https://addisstandard.com/news-as-jawar-et-al-continue-hunger-strike-oromia-region-sees-multiple-protests-demanding-their-release-justice-for-slain-artist-hachalu/ while the Fano youth in Amhara became closely linked to the nationalist NaMA party.50Reuters Staff. (2019, October 8). Ethiopian police teargas protesters in Amhara – local party official. Retrieved May 20, 2021, from U.S. website: https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-ethiopia-violence/ethiopian-police-teargas-protesters-in-amhara-local-party-official-idUKKBN1WN29Y Abiy’s popularity in 2019 onwards plummeted.51Protests in Bahir Dar (2021) and throughout Oromia region in 2020-2021 all contained elements of anti-Abiy/Anti-PP sentiment. Protesters in Oromia burned copies of “Medemer” during riots in 2019, and protesters in Bahir Dar burned pictures of Abiy and PP campaign signs around the city. Again, the faultlines of these acts of dissention are ethnic and territorial — those vying for authority at the local level still had to frame their contests with neighbors and non-co-ethnics in terms of dominance and ‘rightful’ authority.52Interviews in Horo Guduro Wolega zone, West Wolega Zone, Chilga 1 Zone, Gondar Town. Few of these contests resulted in direct intervention by the state government which was both preoccupied with central elite politicking and also awaiting the results of local territorial contests before engaging.53Raleigh and Fuller, 2021. Those that did get a response from the state — including the Somali president’s use of regional ‘special’ police to attack Oromos living in contested areas near the border with Somali region — suggested a clear message of central power and little room for subnational elites to renegotiate their status and power. The attempt by the zone of Wolayta to vie for ‘regional status’ is another example where pushing the boundaries on the ethno-territorial system was no longer feasible, and often fatal, for participants.54Addis Standard. (2020, August 11). Update: Wolaita People’s Democratic Front says 21 people killed as uneasy calm returns – Addis Standard. Retrieved May 13, 2021, from Addis Standard website: https://addisstandard.com/update-wolaita-peoples-democratic-front-says-21-people-killed-as-uneasy-calm-returns/55Austrian Red Cross (2019). Ethiopia COI Compilation, November 2019. Accessed at https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2021013/ACCORD_Ethiopia_COI_Compilation_November_2019.pdf relating to p. 65; 92; 110

The political and election geography of Ethiopia is perilous for Abiy, and his ability to build strong structures before an election looked unlikely given the manifold crises in the state. In response, Abiy has followed a set of regionally variable strategies that built a ‘good enough’ coalition through co-option, force, patronage, and deferred authority. He has taken advantage of regional vulnerabilities and emphasized the strength of the state to create a subnational system that may guarantee that this election returns for him an overwhelming win.

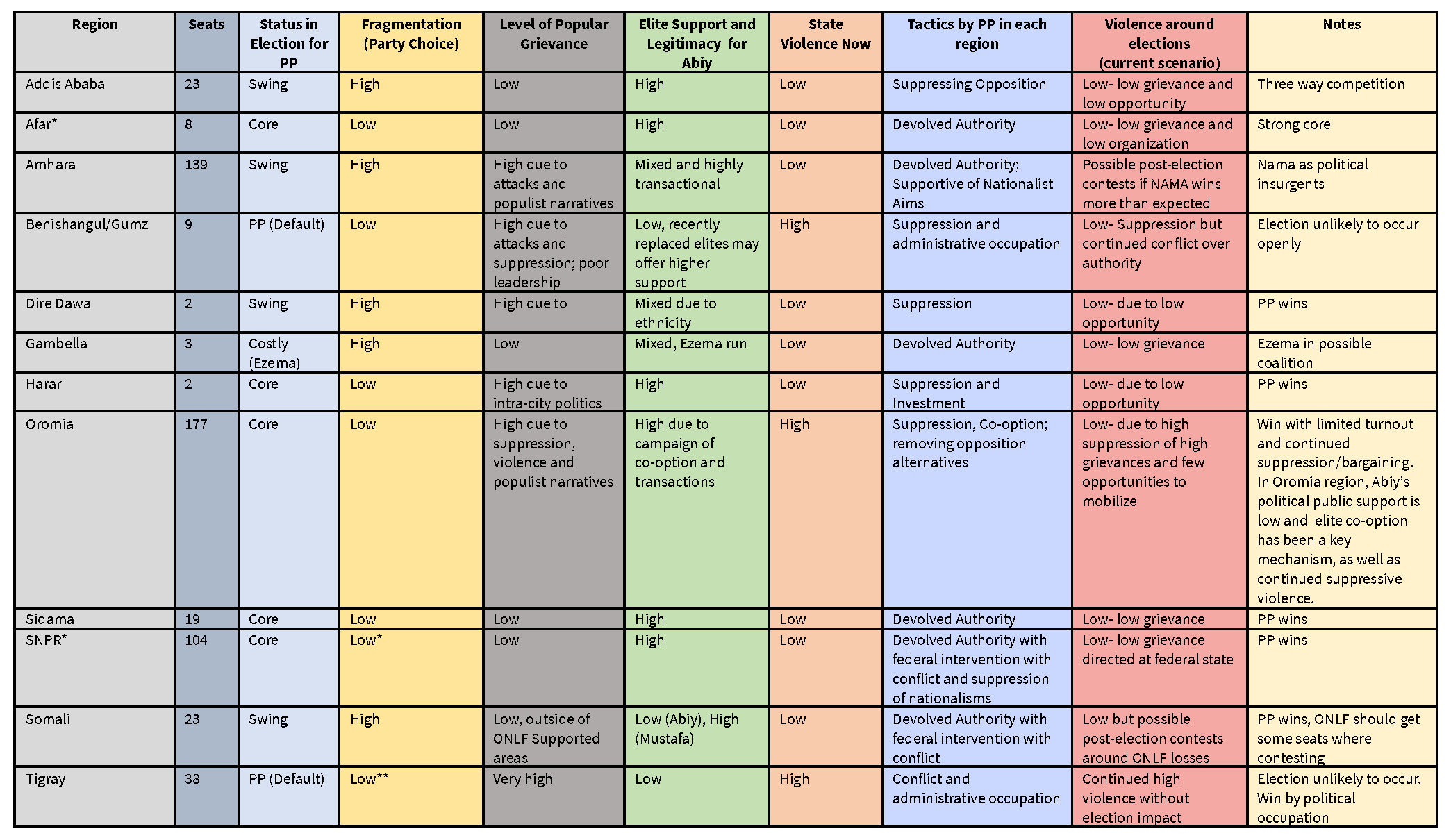

Regional Strategies

The main strategies that Abiy has used to generate significant areas of support include wielding the power of appointments and patronage through rotating bureaucrats and local elites to increase control of their actions; removing alternative and opposition contenders; and, in a more limited application, devolved authority. These strategies are not applied homogeneously across the state: a regionally and even locally heterogeneous approach was necessary to establish a core and loyal coalition given the existing regional contexts. The Oromia and Amhara regions are the key areas to watch in the consolidation of the Abiy regime, and the regime differs with respect to strategies therein (see figure below).

The power of appointment is perhaps the most vital to a new regime. It allows for a reinstatement or replacement of elites at every level. In Ethiopia’s case, little changed locally when Abiy assumed power and the PP was created. Most loyal elites were co-opted to solidify or build existing support.56Clionadh and Fuller, 2021 Strategic, national posts are often kept for loyalists and co-ethnics, who become the inner circle and wield enormous, if dangerous, power. At the national level, Abiy drastically increased the representation of senior Oromo politicians. Whereas previously, their role was proscribed by constitutional limitations, Abiy has increased the Oromo representation significantly. The cabinet mirrored developments in other areas of government. In May 2018, changes instituted by Abiy made the Oromo Democratic Party (OPDO) officials president, prime minister, foreign minister, defense minister, attorney general, director general of revenues and customs authority, and national security advisor.57Abiy tests the military. (2021). Retrieved May 13, 2021, from Africa-confidential.com website: https://www.africa-confidential.com/article-preview/id/12312/Abiy_tests_the_military Advisors include: Shimelis Abdissa (OPDO chairman); Tayyiba Hussan (a former city mayor in Shashemene); Chaltu Sani Ibrahim (deputy chairperson in Hararghe); Jibril Mohammed and Jemal Kedir; and Abadula Gemeda (National Security Advisor). Workneh Gebeyehu is the former foreign minister and part of the intelligence elite who stepped down from his post to take up the reins at OPDO to monitor the region more closely.58Abiy tests the military. (2021). Retrieved May 13, 2021, from Africa-confidential.com website: https://www.africa-confidential.com/article-preview/id/12312/Abiy_tests_the_military

Competition and internal division are not uncommon within Oromia’s politics,59Terje Østebø & Kjetil Tronvoll (2020) Interpreting contemporary Oromo politics in Ethiopia: an ethnographic approach, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 14:4, 613-632, DOI: 10.1080/17531055.2020.1796255 and its most recent manifestations revolve around support for Abiy and support for ethno-nationalism/Oromo dominance. Over the past three years, the Abiy government has gone through nearly half a dozen cabinet and government reshuffles, but key Oromo elites remain as advisors, including Gemeda, a former general, army commander, and head of military intelligence. Gemeda also served as president of the House of Peoples’ Representatives (2010-2018), president of the Oromia region (2005- 2010), and defense minister (2000-2005). Alemu Sime is now director of the political affairs and civil society department at the national secretariat of the PP and, with Binalf Andualem, controls communications for the party’s executive bodies. The list also includes Lencho Bati, a former OLF spokesman, among others.

Abiy repackaged local, former EPRDF elites as they had potentially high alignment and loyalties based entirely on being part of a formal network. Many were moved from their original locations into other locations as PP local authorities to placate an agitated population demanding that PP change elites.60Other elite issues in Oromia come from heightened ethnic nationalism, with autonomy demands coming from all sides in the south, including Kaffa, Hadiya, Wolayta, Gamo, South Omo, Gedeo, Gofa, Bench Maji, Dawro and Silte zones. See: Regional Prosperity Party leaders need to regain autonomy—and rescue Ethiopian democracy – Ethiopia Insight. (2020, September 11). Retrieved May 20, 2021, from Ethiopia Insight website: https://www.ethiopia-insight.com/2020/09/11/regional-prosperity-party-leaders-need-to-regain-autonomy-and-rescue-ethiopian-democracy/ Others were promoted and their empty positions could be given to others. There are holdouts, including in the Wollega regions, where alignment remains low and people representing the government, PP or EPRDF, are killed.61https://www.facebook.com/bbcnews. (2021, May 17). የዞን አመራርን ጨምሮ በምዕራብ ኦሮሚያ 5 ሰዎች በታጣቂዎች ተገደሉ – BBC News አማርኛ. Retrieved June 1, 2021, from BBC News አማርኛ website: https://www.bbc.com/amharic/news-57146500

Abiy’s attempt to quell disorder directed at him by Jawar Mohammed was done through two strategies: Abiy initially considered the Qeerroo movement recruitment as a response to unemployment and under-employment in the region. He coordinated a plan to recruit, employ, and co-opt the local coordinators and local leaders of the movement. This was done through employment in local government at the woreda and kebele level, primarily in the social and cultural areas of government.62Raleigh and Fuller, 2021 63Interviews with Qeerroo youth in Arsi, Hararghe, and Shewa; March 2021 64Interviews with Qeerroo youth in Arsi, Hararghe, and Shewa; March 2021 65Ethiopia’s Oromo youth are disaffected—but also divided, co-opted, and demoralized – Ethiopia Insight. (2021, April 7). Retrieved May 20, 2021, from Ethiopia Insight website: https://www.ethiopia-insight.com/2021/04/07/ethiopias-oromo-youth-are-disaffected-but-also-divided-co-opted-and-demoralized/ The logic behind this co-option is similar to that of the former EPRDF officials who became PP: given an opportunity to be integrated into the patronage network, many took the offer. Others were reportedly offered land plots. Entire areas outside of Shashamene and close to Hawassa are currently farmed by multiple Qeerroo.66Interviews in Oromia region, Feb 2021 Finally, reports from western Oromia suggest that many ‘head’ Qeerroo were also offered money that they invested locally, often in their rural areas.67Interviews in Oromia region, Feb 2021 This co-option strategy is successful because it does not underestimate the power of patronage, appointment, and consolidation. At present, sufficient suppression and co-option have resulted in the Oromia region being likely to return strong electoral support for Abiy.

While curtailing claims of marginalization from the population, Abiy also removed other options for Oromo representation specifically. In November 2019, many of Abiy’s Oromo inner circle boycotted the PP and reinvigorated the Oromo Federalist Congress (OFC), led by Merera Gudina. The OFC later joined a coalition alongside Dawud Ibsa, who leads the OLF,68In 2018, after years as an illegal and violent movement, the OLF became an official Ethiopia party and denounced violence. However, the internal and leadership politics of the OLF is divided, hostile, and at odds with each other, and different wings of the party. The party is currently incapable of organizing itself for a successful run and is hurt by the ongoing links to OLF-Shane (or ‘OLA’), which has perpetuated significant violence in Western Oromia and against other Oromos. and Kemal Gelchu, head of Oromo National Party (ONP). Together they created the Coalition for Democracy and Federalism (CDF).69Addis Standard, (2020, January 4). News: OFC, OLF and ONP agree to form “Coalition for Democratic Federalism” – Addis Standard. Retrieved May 20, 2021, from Addis Standard website: https://addisstandard.com/news-ofc-olf-and-onp-agree-to-form-coalition-for-democratic-federalism/ Because of both government pressures and internal problems common to most opposition groups, the Oromo parties are not viable entities in the upcoming election. In areas across Oromia, this has led to significant grievances about ‘pro-Oromo’ parties being actively disqualified, leaving voters with few to no choices through which to support this ideology. The end result is that Oromo voters do not have an ‘Oromo’ choice beyond the region’s PP. The current lack of outward support for OLF, OFC, and other parties allows the PP to capitalize on being the sole remaining party (opposition members have been arrested, or are disorganized, in the run-up to the election).

Simultaneous with the rise of Abiy and the PP, a new Amhara region nationalist party emerged using the narratives and motivations of territorial expansion and militancy. NaMA has an externally minded agenda that concentrates on territorial acquisition beyond Tigray’s Raya and Wolkayt regions, into Metekel zone of Benshangul/Gumuz, and the Sudanese border region. While the Amhara PP has accepted, if not supported, the territorial claims of Raya and Wolkayt, it regards the additional territorial claims as suspect.70Interview Bahir Dar February 2021 However, NaMA uses attacks on Amhara civilians — which are numerous and growing — as motivations to continue its territorial campaign.71Interview Bahir Dar February 2021 It also has encouraged a narrative that the PP are behind Amhara killings as they continue in areas where the PP is active. While this is a somewhat popular sentiment in urban areas of Amhara and amongst the youth, there is little evidence it has traction (or that people know of NaMA as an electoral factor) in the rural areas.72Interview Bahir Dar February 2021 However, its ability to politically capitalize on the Amhara attacks, and the general rise of nationalism around the state, makes NaMA a formidable candidate during this period of militant nationalism in the country.

Because this is the first election for this regime, its party, and Abiy, no prior information exists about the competence, alignment, and loyalties of local gatekeepers inside the party. How local elites perform in the election is most contentious in Amhara, where the population has choices in terms of representation. Perhaps most out of line with the centralization drive from the Abiy regime is the selective ‘hands-off’ approach it has taken to subnational governance in areas where the regime is highly dependent on support; the area has a viable and popular regionalism/nationalism movement; and the area has a largely homogenous political identity, allowing coordinated and organized opposition to form and be adopted. The Amhara region is one of the sole regions in Ethiopia that fulfills these criteria, which is why the PP and Abiy give the elites a wide berth in their politics and agenda. Other regions, including Sidama, Afar, Somali, and SNNPR, have elements of this policy — the federal government is engaged if conflicts develop but generally leaves problem solving to local authorities.

Abiy’s position on Amhara seems to be to give the region, and its elites, significant authority and autonomy. This community was both central to bringing Abiy to power, and it has largely continued to support him when others — including his own regional supporters — abandoned him. This led to accusations of Abiy being in ‘Amhara pockets’ and operating as a puppet for the region. There is no question that the role of the Amhara elites has been central to Abiy’s retention of power. A consolidated Amhara elite bloc are able to provide significant support to the Abiy regime, while simultaneously working towards two goals that are in line with different camps of Amhara politics. The first is extended dominance of Amhara in territorial areas that Amhara nationalists believe were ‘taken’ by the TPLF (i.e. western Tigray and Raya); the second is a pan-Ethiopian movement that nullifies ethnicity as the basis for administrative and formal recognition. Abiy is assumed to be supportive of the latter, but the majority of his current support base favors the former.73While Abiy enjoys a lot of support from pan-Ethiopian groups in Addis Ababa, his main support base remains in Oromia region. Despite public sentiment of distaste for Abiy, his politicking has left him i the ‘only game in town’ for Oromia and thus he will return high support from that large constituency, which by and large prefers ethnic federalism over a pan-Ethiopian ideology.

The importance of Amhara in the inner circles and the trust in which Abiy places in their regional government is high, despite a coup attempt in June 2019 by an Amhara nationalist. Amhara elites occupy the leadership of the intelligence and federal police; Demeke Mekonnen is deputy prime minister. Other close advisors to Abiy have been placed in senior regional positions in order to sustain and build trust in the new administration: Temesgen Tiruneh is the regional leader and has been in charge of Amhara regional government since after the coup attempt in June 2019. Many others occupy the security branches.

Perhaps the most obvious, if contradictory, evidence of Amhara’s key position to Abiy is his hands-off approach through devolved authority, and limited evidence of a strong federal presence in the region. This is coupled with the free hand he has allowed for Amhara elites to engage in territorial disputes around the region. A strong PP is met with overt suspicion in Amhara, as it is still popularly understood as an Oromo party.74Focus groups and interviews in Bahir Dar Feburary 2021 Despite leaving Amhara politics to Amharas in the hopes of indirect support, Abiy is failing to counter the appeal that NaMA has with Amhara urban communities and youth. These constituents have only experienced “ethnic politics” rather than being exposed to Ethiopian nationalism.75Tezera Tazebew (2021), Amhara nationalism: The empire strikes back, African Affairs, Volume 120, Issue 479, April 2021, Pages 297–313, https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adaa029 Further, attacks on Amhara citizens are widespread across the country, and this has emboldened Amhara nationalists to claim that PP is either directly behind those attacks or unable to protect this community. These claims of insecurity have, in turn, bolstered the case for territorial expansion in order to ‘protect’ Amhara civilians living in western Tigray, Raya, Metekel zone of Benshangul/Gumuz, and the Fashagah border area with Sudan. NaMA is seeking to ‘own’ the territorial expansion drive, which is very popular with Amhara voters, while PP representatives in the region and nationally are relatively quiet about clear territorial invasions by the Amhara youth militia.76Interviews in Bahir Dar and Gondar, April 2021.

Conclusions: Multiple Strategies for Multiple Problems

The use of multiple strategies across the state in the run-up to an election may appear chaotic and without a central reasoning, but they are the responses of a leader facing an election without a coherent political machine. Any leader with a functioning machine can “ensure compliance with the state actions that keep him in office by strategically managing bureaucrats. [To do this,] the leader weigh[s] the political alignment of each jurisdiction to him, each bureaucrat’s loyalty to him, and the bureaucrat’s local embeddedness in a given jurisdiction.”77Philip Onguny (2020) The politics behind Kenya’s Building Bridges Initiative (BBI): Vindu Vichenjanga or sound and fury, signifying nothing?, Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue canadienne des études africaines, 54:3, 557-576, DOI: 10.1080/00083968.2020.1832898 Abiy needs to first assess alignment and loyalty, and — finding it missing or poorly evidenced — begin a strategy of enforcing alignment via the three practices outlined here: co-option, violence, and devolved authority. A combination of these factors allows us to estimate the regime’s core, swing, and costly support at the zonal level across the state. We estimate, from the most likely scenario of electoral performance, that Abiy will succeed in attaining 75% of the vote, with core regions of Oromia, SNNPR, Harar, Somali, and Afar voting in large numbers for PP. Tigray and Benshangul/Gumuz regions already have PP seat occupation. Amhara will be a swing district, and Gambella will be in opposition with both Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa being split between PP, Ezema, and Balderas.

The policy of managing elites is inconsistent, transactional, volatile, violent, and short term. Up to this point it has been based on the quickly shifting advantages that Abiy and his regime could find — often using security forces, formal appointment power, the authority to wield the constitutional permissions, and rhetoric. Those transactions that have defined Abiy to date have resulted in an inability to move forward on his aim with the PP, or to envision an alternative political space. In short, these transactions have now limited his own political space.

The results we predict for these regions are the opposite suggested in recent media analysis: we expect that Oromia will return full support for Abiy, and the Amhara region will return mixed support. The reasons for these results are markedly different: Oromia voters and elites have little choice in who to support, while Amhara voters and elite support is quite tenuous for Abiy. Should these results come to pass, it suggests that going forward, Oromia will be the recipient of significant patronage from the regime, while Amhara will experience a crackdown by the regime for their poor support.

Great efforts have been put into the election by Abiy and the PP. This election is key for him, as it will provide crucial information for his path forward. Leaders in many competitive autocracies, as Ethiopia is shaping to be, conduct elections among pre-determined outcomes so that they can identify the reliable gatekeepers, the wavering supporters, support the ‘churn’ of the elite system, and repopulate the regime’s inner circle to avoid known vulnerabilities. Critically for this election, the contest is internal to the party, and will test the consolidation of the PP in the face of severe internal dissension.

Annex 1: Index

The following table breaks down each of Ethiopia’s regions and details the most likely electoral violence conditions based on input factors including: PP party development status, party fragmentation, levels of popular grievance, elite support for PM Abiy, current levels of state violence, and PP tactics for support/coercion. A combination of these factors allows us to estimate the regime’s core, swing, and costly support at the zonal level across the state.