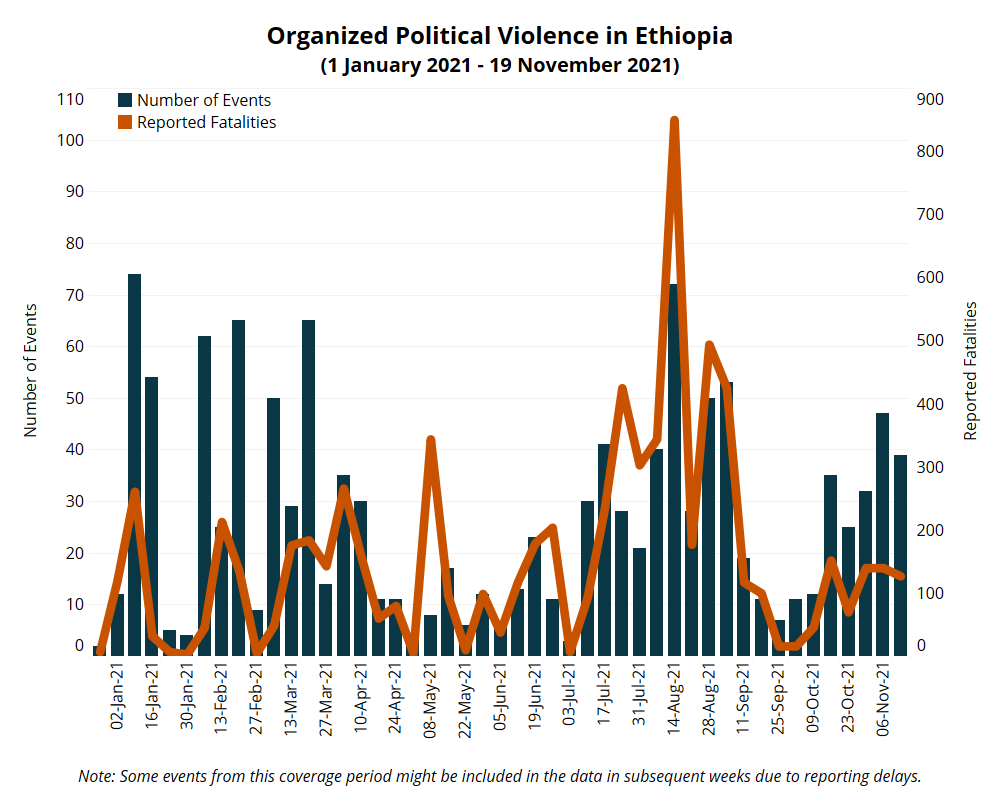

By the Numbers: Ethiopia, 2 April 2018-19 November 20211 Figures reflect violent events reported since Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed came to power on 2 April 2018.

- Total number of organized violence events: 2,243

- Total number of reported fatalities from organized violence: 12,825

- Total number of reported fatalities from civilian targeting: 5,820

By the Numbers: Ethiopia, 13-19 November 20212Some events from this coverage period might be included in the data in subsequent weeks due to reporting delays.

- Total number of organized violence events: 39

- Total number of reported fatalities from organized violence: 127

- Total number of reported fatalities from civilian targeting: 4

Ethiopia data are available through a curated EPO data file as well as the main ACLED export tool.

Situation Summary

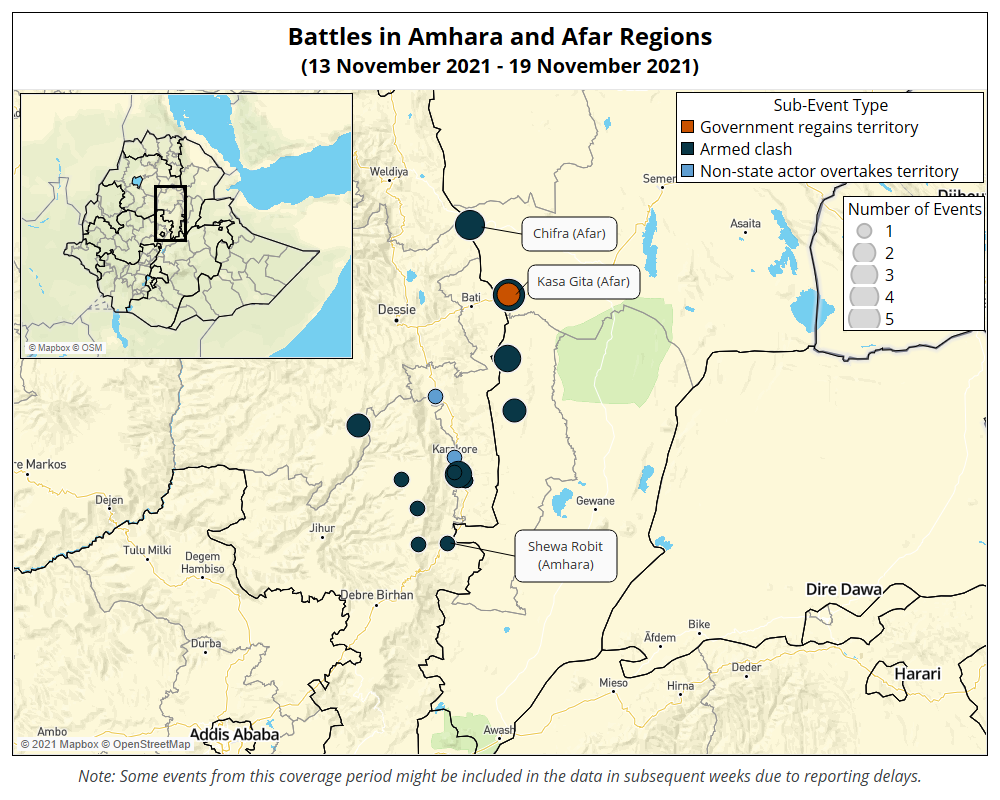

Clashes continued throughout last week between the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) accompanied by regional special forces and militias. In the Afar region, TPLF attempts to move eastward toward the Addis-Djibouti highway were thwarted by ENDF and Afar regional special forces and militia allies. Battles were fought throughout the week on the Kasa Gita and Chifra fronts; many such battles included heavy shelling. In the Amhara region, Amhara regional special forces and militias were pushed back by TPLF and Oromo Liberation Front (OLF-Shane) forces as they continued to advance southward through the mountains. By the end of the week, clashes were reported in areas surrounding Shewa Robit, the southern end of the Oromia special zone in the Amhara region (see map below). Intense battles were fought for control of Were Ilu town, which (at time of writing) remains under the control of the Ethiopian military.

In Benshangul/Gumuz region, the head of the Metekel zone communication office and the mayor of Gilgel Belles town were reportedly arrested by federal soldiers stationed at a command post in the Metekel zone under suspicion of having links with armed groups. The head of regional anti-insurgency forces was likewise arrested in the Kamashi zone earlier in the week. On 19 November, Benshangul/Gumuz region special police forces clashed with a “TPLF affiliated armed group” in unspecified locations described as being “near the border with Sudan” (OBN, 19 November 2021). The police forces claimed to have killed an unspecified number of militants and captured armaments, including anti-tank mines.

Despite ongoing clashes with OLF-Shane forces in the Oromia region and a generally deteriorating security situation throughout the country, the Oromia regional government reversed its decision to impose a state of emergency curfew, citing economic reasons (Addis Standard, 18 November 2021). The curfew had been imposed just a few days earlier (Addis Standard, November 13, 2021).

Meanwhile, on 19 November, following an attack by unidentified gunmen on Amhara militiamen in Mettu Selassie, clashes between Oromo and Amhara communities in Nono in the West Shewa zone in the Oromia region resulted in the death of at least 20 people.3Due to reporting delays, this event will be added to the dataset next week. Local government officials have ordered an investigation to be conducted (DW Amharic, 22 November 2021).

Also in the Oromia region, clashes were reported throughout the week in areas east of Shambu town in Horo Guduru Wollega zone as Oromia regional special forces and allied military troops battled OLF-Shane forces in the area. Additional battles were reported in the North Shewa zone of the Amhara region, in Leman Kare Kora kebele, and in Kuyu woreda. Fifty-two people with suspected links to the OLF-Shane were reportedly arrested in Arsi Negele town in the Arsi zone; 152 individuals were arrested in Inchini, Adda Berga woreda in West Shewa zone in the Oromia region.

In the Somali region, regional special police forces claimed via state-associated media that their forces had “foiled” an attempted attack by the former regional police commander (Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation, 20 November 2021). No further details were provided. In the last few years, the Somali region has been one of the more stable regions in the country.

Weekly Focus: The TPLF’s Threat of Secession

Last week, a representative of the TPLF indicated that the group might be interested in holding a referendum for secession in the Tigray region (Tigray Media House, 15 November 2021). Following this press release, the mayor of Addis Ababa city stated that “if there is a need to establish Tigray state, they can establish Tigray as per the procedures of the constitution” (EBC, 16 November 2021). While provisions in the constitution seemingly allow for the establishment of a Tigray state, this weekly focus explores the limits of secession as a mechanism for solving the conflict in northern Ethiopia.

According to Article 39 (1) of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Constitution, “every Nation, Nationality and People in Ethiopia has an unconditional right to self-determination, including the right to secession” (Article 39 (1)). This right was first introduced in the Addis Ababa Charter in 1991 and provided a legal basis for Eritrea to secede from Ethiopia on 23 May 1993 (Transitional Period Charter of Ethiopia, 1991, Article 2; see also Articles 6-13). This charter was considered the interim constitution of the TPLF-led Transitional Government of Ethiopia. In principle, the 1991 Transitional Government of Ethiopia followed the Soviet model of ethnic federalism. The Transitional Government’s Council of Representatives consisted of 87 members — 32 of which were from the TPLF-led Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). Twelve representatives were from Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) and the rest were representatives of small ethnic-based liberation fronts and prominent people.

To enjoy the right to secession under the Ethiopian constitution, there are three major preconditions. First, the requesting group is required to be a “Nation, Nationality, and People in Ethiopia.” According to the constitution, nation, nationality, or people “is a group of people who have or share….a common culture or similar customs, mutually intelligible language, belief in common or related identities, a common psychological make-up, and who inhabit an identifiable, predominantly contiguous territory” (Article 39 (5)). Second, the question of secession must be approved by a two-thirds majority of the concerned legislative council of the nation, nationality, or people. Third, if said legislative council approves of secession, a referendum must be held. The federal government is required to organize a referendum within three years of this approval (see Article 39 (4)).

Based on this legal framework, issues of Tigray secession are already beset by significant complications. First, the Tigray region (as it exists within currently-drawn boundaries) does not consist of a nation, nationality, or people that believe “in a shared or related identity” as defined by the constitution. Residents of Raya, located in the Southern Tigray zone and Welkait locality in the Western Tigray zone, have spent two decades attempting to join the Amhara region. The same is true for some kebeles in the Eastern Tigray zone which have demanded to be administered by the Afar region. To complicate the issue further, Amhara regional special forces have controlled the Western Tigray zone and parts of the Southern Tigray zone since the beginning of the conflict in Tigray. Western Tigray zone — Welkait — is currently administered by the Amhara regional government. Similarly, the Afar regional government controls and administers the kebeles which they consider to be part of the Afar region. According to the constitution, these Afar and Amhara regional governments do not have the legal grounds to administer areas that are officially within the Tigray region. Before initiating the secession process, politicians from contested areas would have to resolve these identity-based demands to avoid further conflict in the region.

Second, according to the federal government, the Tigray region does not have a legitimately elected legislative council. Tigray region officials held a regional election in September 2020 without the federal government’s approval. According to the constitution and other electoral regulations, only the National Electoral Board of Ethiopia (NEBE) has the authority to conduct federal and regional elections (see Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Constitution Article 102 (1); National Electoral Board of Ethiopia Establishment Proclamation, Proclamation No.1133/2019, Article 7(1); Ethiopian Electoral, Political Parties Registration and Election’s Code of Conduct Proclamation, Proclamation No. 1162/2019). Requests by Tigray region officials for NEBE to conduct the regional election in Tigray were denied based on the federal government’s wish to delay the sixth general election due to the COVID-19 pandemic (National Electoral Board of Ethiopia-NEBE, 24 June 2020).

While according to the law, the federal government must technically allow secession as the constitution specifies, it has historically used force to thwart any attempt to disrupt Ethiopian unity. Throughout the years, several moves toward autonomy from the central government have been effectively halted. For example, a threat by the former Somali regional president, Abdi Illey, to initiate secession was quickly stopped after Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed sent federal troops into Jigjiga and took Illey into custody (Hagmann, 11 September 2020). The ONLF sparked a decades-long war after it demanded secession for the Somali region in 1994 (Reuters, 12 August 2021).

Article 39 of the Ethiopian constitution is one of the most hotly debated topics in Ethiopian politics. For some, the article represents protection from the over-reach of any one ethnic group and establishes a right to self-rule. In practice, however, its implementation is complicated and could spark a never-ending spiral of violence.