Last updated: 08/08/2024

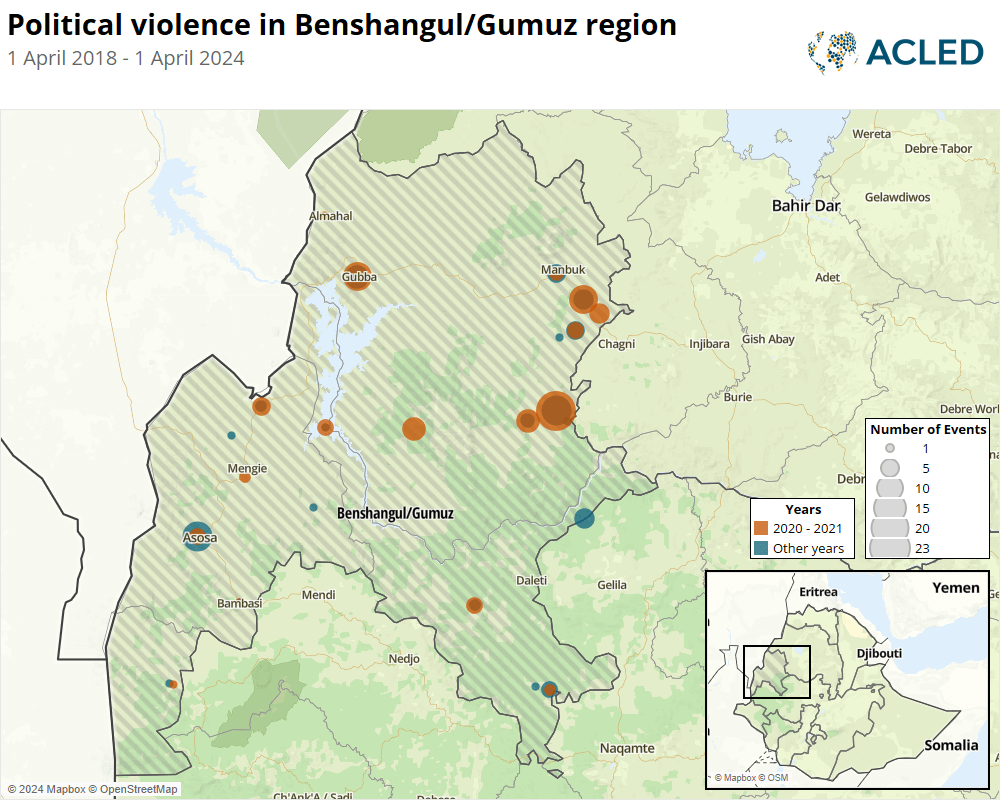

Benshangul/Gumuz region is located in western Ethiopia along the border with Sudan, and it shares internal borders with Amhara and Oromia regions. The region hosts the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. Benshangul/Gumuz was the site of intense ethnic-based killings from 2020 to 2021 (see map below). During this period, Metekel zone in the region’s north was one of the most violent areas in the country, with over 1,307 reported fatalities recorded. The political violence dynamic in the region is complex, with competing elites divided along ethnic lines and awarded political superiority through the ethno-federalist system.

The region has five indigenous ethnic groups — Berta (also known as Benshangul), Gumuz, Shinasha, Mao, and Komo — but other ethnic groups also live in the region. According to the last official national census in 2007, out of the region’s 670,847 inhabitants, 173,743 belong to the Berta ethnic group, 142,557 to the Amhara, 141,645 to the Gumuz, 89,346 to the Oromo, 50,916 to the Shinasha, 28,467 to the Agew-Awi, 12,744 to the Mao, and 6,464 to the Komo ethnic group.1Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Population Census Commission, ‘Summary and Statistical Report of the 2017 Population and Housing Census,’ December 2008 By 2019, it was estimated that the region’s population had reached around 1.1 million, with 77% living in rural areas.2United Nations Children’s Fund Ethiopia, ‘Regional Situation Analysis of Children and Women,’ December 2019

The capital city of Benshangul/Gumuz is Asosa. The region is divided into three administrative zones (Metekel, Asosa, and Kamashi), 17 woredas, two special woredas (Pawe and Mao Komo), and 33 kebeles. Benshangul/Gumuz’s economy relies on agriculture, with large amounts of land leased to mainly international investors.3James Keeley et al., ‘Large-scale land investment in Ethiopia: How much land is being allocated, and features and outcomes of investments to date,’ June 2018

Given ongoing instability in the region and the large number of inhabitants displaced to camps in the neighboring Amhara region, the six general election was held for only 34 out of the 99 regional council seats. Elections were not held in Daleti, Kamashi, Metekel, and Shinasha special zones. NEBE planned to hold elections in 17 electoral constituencies in Benshangul/Gumuz in December 2021. However, due to the state of emergency declared on 2 November 2021, NEBE was forced to extend the election in the region.4National Electoral Board of Ethiopia (NEBE), 19 October 2021 Politically, Benshangul/Gumuz is the only region that did not establish a new government in October 2021, as elections were not held for the majority of its regional council seats. As of May 2022, 66 of 95 seats in Benshangul/Gumuz region remain unelected.5Ethiopia Insider, ‘Election Board to conduct data collection to assess security situation in Benishangul Gumuz region,’ 11 May 2022 The election was finally held in the remaining constituencies in June 2024, with the majority of seats won by the ruling party, Prosperity Party.6NEBE, 11 July 2024

Metekel zone

Since the change in government in 2018, until 2022, Metekel zone was one of the most violent locations in the country. Between 1 April 2018 and 1 April 2024, ACLED records 1,574 reported fatalities in the zone as a result of political violence, and this is likely a conservative estimate. Most fatalities recorded result from attacks by unspecified ethnic militias on ethnic Amhara civilians.

Official sources often refuse to identify the perpetrators of violence. ACLED data indicates the perpetrators are likely Gumuz ethnic militias that may be associated with more officially organized ethno-nationalistic movements like the Gumuz People’s Democratic Movement and the Benishangul People’s Liberation Movement. Some leaders of the Oromo Liberation Front believe splinter groups that once belonged to the front could be responsible.7Semir Yusuf, ‘Drivers of ethnic conflict in contemporary Ethiopia,’ Institute for Security Studies, 9 December 2019 Meanwhile, government sources have accused “anti-peace forces” of having links with Sudan.8Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation (EBC), ‘The messengers of the terrorist TPLF who infiltrated the border areas of Benishangul Gumuz were destroyed,’ 19 November 2021

The conflict in Metekel has deep roots. During a severe drought in 1984 and 1985, ethnic Amhara from areas of Wollo were resettled in areas of Benshangul/Gumuz with fertile land. This led to conflicts over land.9Maria Gerth-Niculescu, ‘Ethiopia’s Troubled Western Region,’ Deutsche Welle, 2 August 2021 The issue was exacerbated by the ethnic-based politics of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, which came to power in 1991 and assigned political ownership of the area to Gumuz and Shinasha ethnic groups, limiting the political and economic rights of non-indigenous ethnic groups. Under Ethiopia’s ethno-federal system the regional state lacks institutional and political arrangements to accommodate the political claim of non-indigenous groups at any level of government.10Dagnachew Ayenew Yeshiwas, ‘Explaining Metekel Syndrome: Revisiting the Prolonged Ethnic Violence,’ CARD, 25 September 2020

In 2020, as fatalities resulting from attacks on Amhara civilians increased, Amhara authorities began to demand additional action be taken. In December 2020, the chief of police in Amhara region requested permission to deploy officers in Benshangul, and Amhara officials warned that they would intervene if attacks continued.11Tom Gardener, ‘All Is Not Quiet on Ethiopia’s Western Front,’ Foreign Policy, 6 January 2021 Benshangul/Gumuz regional state officials responded to these requests by labeling them “repeated threats of intimidation.”12Metekel Zone Communication Bureau, ‘A statement from Benishangul Gumuz’s Prosperity Chapter:’ 15 December 2021

On 23 January 2021, the federal government declared a state of emergency in Metekel zone,13EBC, ‘It has been decided to create an organization to protect the community from attacks by organizing militias recruited from displaced persons: Mr. Demeke Mekonen,’ 23 January 2021 with federal troops taking control of security in the area. On one hand, the move satisfied the demands of officials from the neighboring Amhara region without exposing Metekel zone to the complications that would have occurred if Amhara region had become involved directly. On the other hand, it resulted in federal troops’ heavy crackdown on ethnic Gumuz communities, including alleged massacres of civilians, and the dismissal of political leaders.14Addis Standard, ‘News: Security forces kill scores of civilians, arrest several in Metekel after attack by rebels killed three, wounded seven; Ethiopia accuses Egypt & Sudan for persistent violence,’ 8 March 2021; Negasa Desalegn, Shewaye Legese and Negash Mohamed, ‘Apologies from Benshangul Gumuz Prosperity Party,’ DW Amharic, 11 February 2021

The regional government has made significant efforts to advance peace in Metekel zone, yielding varying degrees of success. This includes involving communal elders in the process. For instance, in June 2022, a traditional peace and reconciliation ceremony was held in Wemebera woreda, bringing together selected elders from 11 kebeles of Wemebera woreda.15Fana Broadcasting Corporate,’It has been revealed that the area is returning to peace through traditional reconciliation ceremonies using age-old conflict resolution methods in the planting zone,’ 24 June 2022 In August 2022, around 246 militants surrendered to the Metekel zone command post in Dangur woreda.16EBC,’246 militants who accepted the government’s call for peace in the Metekel zone, Dangur district, have returned,’ 9 August 2022 The army has also implemented the training of communal militias17EBC,’It has been decided to create an organization to protect the community from attacks by organizing militias recruited from displaced persons: Mr. Demeke Mekonen,’ 23 January 2021 and taken steps toward reshaping the police into a multi-ethnic force.18EBC,’A leadership transition is being made based on a composition of the ethnic groups living in the Metekel zone: the task force,’ 20 February 2021 In October 2022, a peace deal was signed between the regional government and the Gumuz People’s Democratic Movement (GPDM), followed in December 2022 by a deal with the Benishangul People’s Liberation Movement.19Addis Standard, ‘News: Benishangul Gumuz region signs peace agreement with second rebel group, deal signed in Sudan,’ 12 December 2022

Violence reduced significantly in Benshangul/Gumuz region in 2023, indicating the peace deals’ success. While security in the region has improved significantly, root causes of the conflict have not been resolved. Instability in many parts of the region led to the cancellation of voting during the last national election; given the decrease in violence, the conditions may allow elections to be held in the near future.20VOA Amharic, ‘Political parties of Benshangul Gumuz demand that disrupted elections be held in the region,’ 29 March 2023

Kamashi zone

Clashes sparked by the September 2018 assassination of the Kamashi zonal administrator in West Wollega of Oromia region led to ethnic violence in Kamashi town in October 2018, which is inhabited by Oromo and Gumuz ethnic groups.21Mehdi Labzaé, ‘Benishangul conflict spurred by investment, land titling, rumors,’ Ethiopian Insight, 8 March 2019 Thousands were displaced, and tensions along the Kamashi zone/Oromia regional border resulted in occasional clashes.22Ermias Tesfaye and Solomon Yimer, ‘Tens of thousands flee Benishangul after Oromia border dispute flares,’ Ethiopia Insight, 4 October 2018