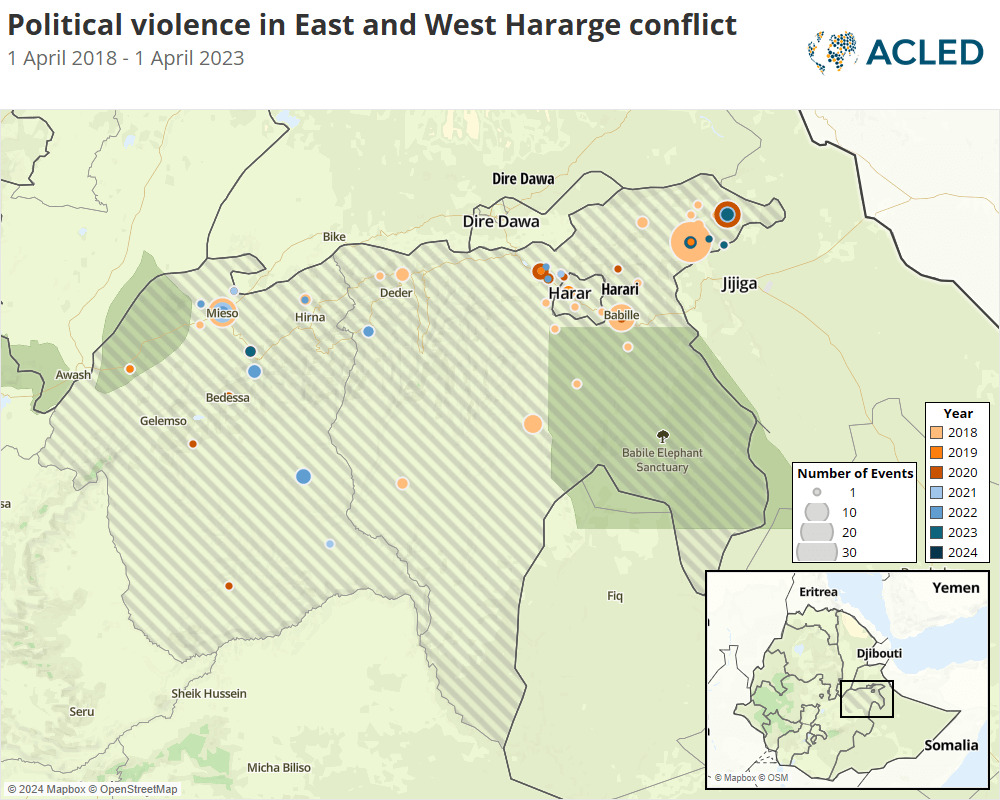

In 2020, the East and West Hararge zones of Oromia region were characterized by short, intense bursts of violence (see map below). This violence revealed that local youth groups have the capacity to challenge government control during key moments of instability, creating a dynamic that has been costly for the federal government in terms of security resources that need to be deployed. Outside the major cities, grazing land conflicts have been transformed into prolonged violence between the Oromo and Somali ethnic groups who reside in the area. While not a new phenomenon, these conflicts have been exacerbated by divisive ethnic rhetoric and the perceived weakness of the federal government.

In late October 2019, rumored attempts to harm a popular Oromo activist, Jawar Mohammed, sparked violent protests on 23 October in East Hararge, part of a wave of such protests across the whole Oromia region that lasted days. A second wave of demonstrations erupted following the killing of Hachalu Hundessa, a renowned Oromo singer, in the summer of 2020 in Addis Ababa. During both rounds of demonstrations, demonstrators blocked roads, destroyed infrastructure, and attacked ethnic minorities throughout the Oromia region, including in Hararge. The demonstrations were organized by Oromo youth organizations called Qeerroo. According to local sources in the East Hararge zone, federal police forces were slow in mobilizing and responding to the crisis in the zone, and in some cases, local Qeerroo militias were mobilized to provide security and even make demands over resource allotment and utilization.

The East and West Hararge zones’ close proximity to the Somali border and the long-standing border disputes there have led to inter-communal violence inflamed by ethno-nationalist rhetoric. Clashes have repeatedly resurfaced as ethno-federalism continues to undermine the federal government’s authority.1Befekadu Hailu, ‘Reforming Ethiopian ethnofederalism,’Ethiopia Insight, 30 December 2022 This has led to a heavily armed population and highly mobilized ethnically-exclusive militias – many espousing the Oromo independence ideology of the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) — referred to by the government as the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF)-Shane.

In the context of rising ethno-nationalist ideals within the country, formerly tribal conflicts over resources have increased in scale and widened to potentially include members of the ethnic groups even far away from the actual conflict locations. The ethnic clashes that occurred on the borders of East and West Hararge zones of Oromia region and Somali region’s Fafan zone are examples of this amplification as the ethnic clashes culminated in pogrom-like attacks of ethnic minorities in Jigjiga city on 4 August 2018,2Tobias Hagmann and Mustafe Mohamed Abdi, ‘Inter-ethnic violence in Ethiopia’s Somali Regional State, 2017 – 2018,’ London School of Economics, March 2020 following months of clashes along the Somali/Oromia border area.3Abdur Rahman Alfa Shaban, ‘Ex-prez of Ethiopia’s Somali region slapped with criminal charges,’ Africa News Armed clashes between ethnic militias occurred during the first week of January 2021, despite high-profile peace conferences between the Oromia and Somali region’s leaders.4Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation, ‘Prime Minister Abiy thanked the leaders of Oromia and Somali region for their exemplary actions,’ 27 January 2021

Bringing East and West Hararge zones under consistent government control required federal and regional engagement with Qeerroo youth — which had occurred under more consistent government control — will require federal engagement with the Qeerroo organizations and addressing the prevalence of armed militias operating outside of government control throughout the region. Arrests, violence, and other repressive measures risk radicalizing moderate Oromo youths and creating flashpoints of additional violence.

This conflict profile was last updated on 05/08/2024.