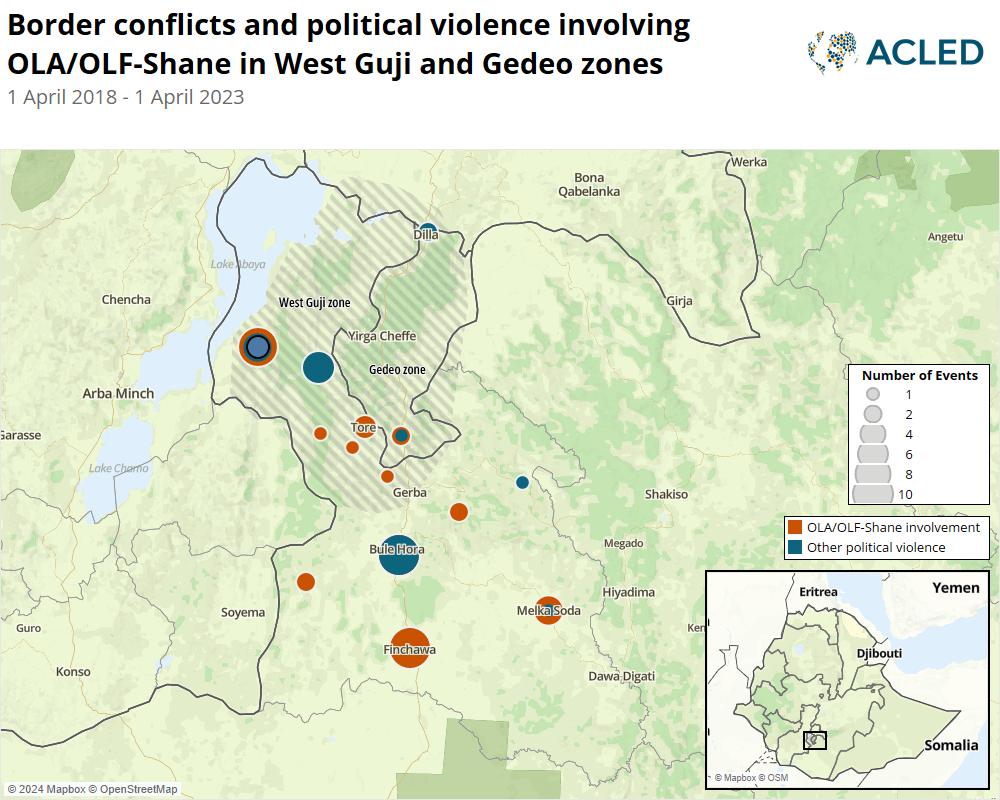

West Guji zone is located on the eastern banks of Ethiopia’s Abaya lake, around 370 kilometers south of Addis Ababa. Part of the expansive Oromia regional state and bordered to the west by several small zones that are part of South Ethiopia region, the area has a history of border disputes and local conflicts that reflect deep issues with Ethiopia’s ethno-federalist arrangement. The area is inhabited by the Gedeo and Guji Oromo ethnic groups.1Ethiopia Observer. ‘Interview: The Makings of a Gedeo Crisis’ 4 April 2019 East of West Guji zone is Gedeo zone, an exclave of the South Ethiopia region. Gedeo zone is named after the Gedeo ethnic group — the primary inhabitant of the zone. Conflict along Gedeo zone’s borders with Oromia is common. Border conflicts involving ethnic claims to land are the primary cause for conflict in this area. Since 2021, events involving the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) — referred to by the government as the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF)-Shane — have driven additional conflict and displacement (see map below).

Border conflicts

Conflict in West Guji and Gedeo zones is the result of territorial claims and counterclaims over administrative boundaries made by competing elites who use ethnic division to fuel conflict. Before 1991, the area fell under the Sidamo Province, and conflict was limited to interpersonal disputes that were usually solved using communal councils.2Bahru Zewde, A History of Modern Ethiopia, 1855-1974, The Journal of Modern African Studies, September 1993 This changed after the current constitution was adopted in 1995, with formal administrative divisions drawn with regional boundaries falling along ethnic lines — the Guji Oromo ethnic group under the Oromia region and the Gedeo ethnic group in the former Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples region (SNNPR). Earlier during the period of transition (from 1991 to 1995), conflict arose over the inclusion of certain kebeles in the Gedeo and West Guji zones. This ongoing conflict between the two groups is mainly centered around claims to land for agricultural production or grazing.

Guji Oromos, who then inhabited areas of SNNPR claimed to have become minorities in what they viewed as their traditional homeland.3Asebe Regassa Debelo, ‘Dynamics of political ethnicity and ethnic policy in Ethiopia: national discourse and lived reality in the Guji-Gedeo case,’ 2012 On the other side, the Gedeo ethnic group, who were previously included in the West Guji zone, have been accused of being ‘settlers’ and attempting to encroach on the boundaries of the West Guji zone. This has led to them being targeted by Guji youth, as well as local woreda and kebele officials. Boundary demarcation referendums held in the area sparked major clashes in 1995 and 1998, with additional violent events occurring at regular intervals throughout the past 30 years.

Widespread unrest and social mobilization in Ethiopia leading up to the resignation of Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn limited the capacity of state security institutions and local government to address remote conflicts like those in West Guji, giving rise to renewed and intensified conflict in 2018 and 2019. In 2018, the conflict was fueled by claims that Gedeo nationalists were advocating for the remapping of some locations inside Guji zone into Gedeo zone.4Semir Yusuf, ‘Drivers of Ethnic Conflict in Contemporary Ethiopia,’ ISS Africa Monograph 202, December 2019 Elites from both sides took advantage of a weakened institutional capacity to enforce law and order and mobilized ethnic militias in attempts to seize territory or political resources. This promotion of violence has highlighted the instability of the current political system, and further violence is expected to continue to occur as long as the state remains weak in the area.

Under the ethno-federalist system, areas like West Guji and Gedeo will continue to face instability, as access to land is, as described by Nigusie Angessa — an expert on conflict in the area — a “commodity upon which all the constitutional rights and policy provisions are put into effect, guaranteed, and exercised.”5Nigusie Angessa, ’Conflict-Induced Internal Displacement in an Ethnolinguistic Federal State Gedeo-Guji Displacement in West Guji and Gedeo Zones in Focus.’ in ‘Ethiopia in the Wake of Political Reforms,’ Melaku G. Desta et al. (eds.), 2020 This is especially evident in areas where the Guji Oromos are awarded ‘political superiority’ in West Guji zone as a result of ethnic federalism policy, exacerbated by their economic precarity compared with the relative economic stability of the minority ethnic groups in the zone (Gedeo and Amaro). This imbalance of political power and economic frustration is exposed by political elites on both sides, who use the existing political infrastructures of repression against minority residents, thus triggering widespread conflict and displacement.

A key feature of the West Guji and Gedeo zones conflict lies in the high levels of displacement by civilians caught between warring parties. According to the International Organization for Migration, nearly 1 million people were displaced as part of the conflict that erupted in the spring of 2018.6International Organization for Migration (IOM), ‘IOM Launches USD 22.2M Appeal for Gedeo, West Guji Displacement Crisis in Ethiopia,’ 24 July 2018 While most of the displaced have since returned to their homes, the conflict continued to flare up. In early March of 2021, a deadly attack on communal leaders from Guji and Amaro zones who were meeting in Gelana woreda reportedly left six people dead.7Amaro Woreda Government Communication Affairs Office, ‘The tragic death of civilians continues in Amaro land, three innocent herdsmen died in the attack by armed militia forces in Amaro district in just two days, one herdsman was seriously injured,’ 18 March 2021

Ethnic militias and the OLA/OLF-Shane

Most actors recorded by ACLED in the West Guji and Gedeo conflict are associated with ethnic militias belonging to the Guji Oromo, the Gedeo, or the Amaro communities. Also active in the Guji area is the OLA/OLF-Shane, which often clashes with government forces.

OLA/OLF-Shane activity in Guji was limited for a time after the OLA/OLF-Shane Guji regional commander, Elias Gambella Gollo, accepted a peace offer mediated by traditional elders in January 2019.8Borkena, ‘Oromo Liberation Front war lord in South Ethiopia accepts peace offer,’ 15 January 2019 The blurring of actors and overall remoteness of the West Guji area makes distinguishing OLA/OLF-Shane attacks from other ethnic-militia activities difficult, and even local news agencies often default to the OLA/OLF-Shane when they are unable to identify a perpetrator.

In 2022 and 2023, along with a rise in activity by OLA/OLF-Shane throughout Oromia, OLA/OLF-Shane-linked militias were able to gain control of many locations throughout West Guji and Guji zones.9Yonatan Zebdiyos, ‘Worrying Security Situation in Eight woredas of Guji zone,’ VOA Amharic, 5 February 2022 While the government maintains control of main towns, the OLA/OLF-Shane militias control many locations in rural areas, challenging the government’s ability to operate beyond main towns.

This conflict profile was updated on 08/08/2024.