November at a Glance

Vital Stats

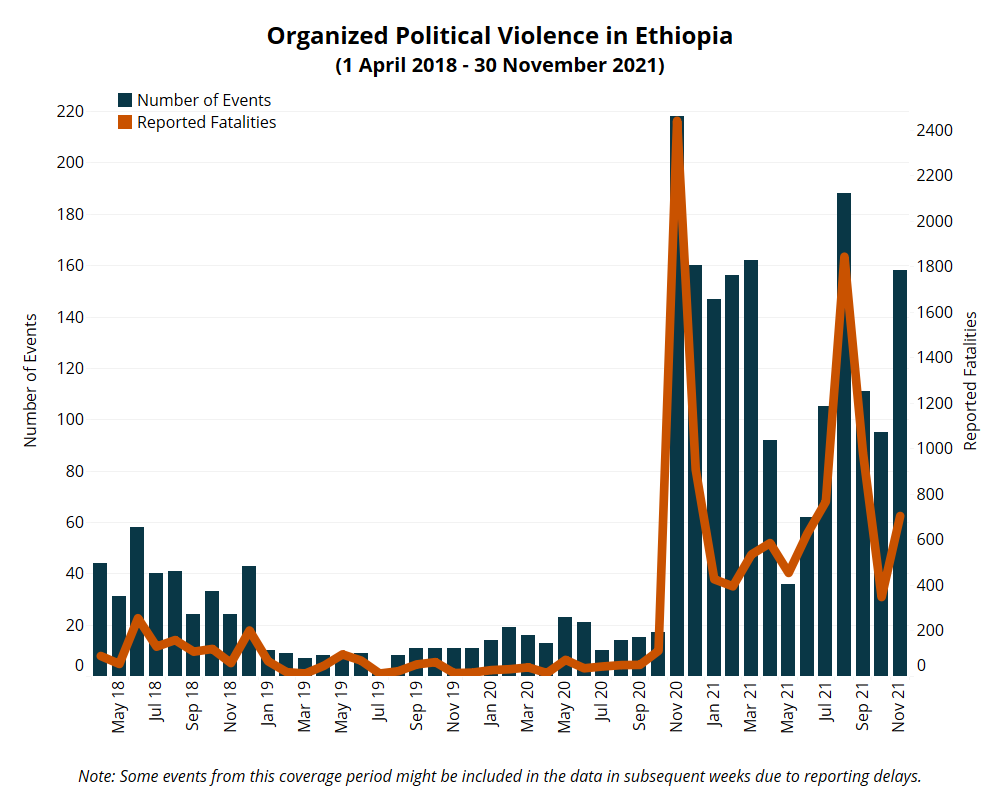

- ACLED recorded 158 organized political violence events and 705 reported fatalities in November.

- Oromia region had the highest number of reported fatalities due to organized political violence in November with 243 reported fatalities. Afar region followed with 200 reported fatalities, while the Amhara region had nearly as many with 199 reported fatalities.

- In November, the most common event type was battles, with 127 events and 557 fatalities reported.

Vital Trends

- At the beginning of November, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) controlled most areas of Wag Hamera, North Wello, South Wello, Oromia special, and North Shewa zones of Amhara regions. By the end of the month, government forces had regained most strategic areas.

- In November, armed clashes between TPLF forces and the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF), Afar regional special forces, and Afar militias were recorded in Kasagita, Chifra, and Burka in Afar regions.

- Many demonstrations against TPLF and the OLF-Shane, as well as the intervention of foreign countries, were held across the country.

- A state of emergency was declared in November after TPLF forces took control of Kombolcha, Dessie, and Burka towns in the Amhara region.

- Many people were arrested and accused of having links with either TPLF or OLF-Shane.

In This Report

- Situation Summary

- Monthly Focus: United Front of Ethiopian Federalist and Confederalist Forces

November Situation Summary

At the beginning of November, TPLF forces captured Dessie and Kombolcha towns in the South Wello zone in the Amhara region. Members of OLF-Shane, which is allied with TPLF, also took control of Sanbate and Kemise towns in the Oromia special zone in the Amhara region (Odaa Tarbii, 31 October 2021; Reuters, 1 November 2021). This sparked concerns throughout the country that TPLF forces would move further south and threaten the capital city, Addis Ababa, and other locations throughout the country. As a result, the federal government declared a state of emergency on 2 November.

The state of emergency allows security forces to search and arrest individuals without a warrant. It also allows the closing of streets and the partial or full suspension of the administrative governance structure and the replacement of administrators if there is a security threat (A State of Emergency Proclamation No 5/2021). Under the state of emergency, the government may order anyone with firearms or prior military service to take military training and join military missions; the government can compel people to hand over their firearms if they are unable to join the military.

As a result of the state of emergency, many people accused of having links with TPLF or OLF-Shane were arrested in various areas of the country. Moreover, the Ethiopian Media Authority (EMA), a government body, issued a warning to private media, asking journalists to consider the implications of reporting in Ethiopia’s current environment. The deputy director of EMA “urged the media to shift from the traditional way of reporting and instead focus on reports that help Ethiopians transcend the difficulties they’re facing”(Addis Standard, 12 November 2021). EMA also wrote a warning letter to CNN, BBC, Reuters, and the Associated Press, asking them to refrain from “disseminating unsubstantiated information,” or the government would revoke their license to operate in the country (Ethiopian Media Authority, 19 November 2021). The deputy director of EMA asked Ethiopian journalists who work for foreign media outlets to “protest the false propaganda against their country” and show the world the reality their country is in” (Addis Standard, 12 November 2021).

By the end of the month, the state of emergency command post decided that only authorized people and institutions are allowed to provide information on ENDF’s activities. The government also issued a warning to the United States (US) embassy after the embassy issued a warning on 24 November 2021 about a possible terrorist attack as, according to the government, the warning from the embassy was far from the truth on the ground (Addis Standard, 25 November 2021). The Ethiopian government also declared four diplomats of the Ireland embassy in Addis Ababa persona non grata.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed announced his decision to lead ENDF forces “from the front” on 24 November (EBC, 30 November 2021). Deputy Prime Minister Demeke Mekonnen has reportedly taken over the prime minister’s duties overseeing government functions (BBC Amharic, 24 November 2021). Since then, the government has regained control of many areas in both the Amhara and Afar regions. By the end of the month, ENDF and its affiliated forces controlled Chifra, Kasa Gita, and Burka in the Afar region. In the Amhara region, the government regained control of the mountains surrounding Bati town in the Oromia special zone.

As the areas affected by conflict expanded, the humanitarian crisis also increased in northern Ethiopia. More than 110 people, including women and children, have died due to a lack of food, water, and medicine in the Wag Hamra zone in the Amhara region (BBC Amharic, 5 November 2021), which has been under the control of the TPLF since July. Additionally, reports have emerged of killings, rapes, and property destruction carried out by TPLF and OLF-Shane in both Amhara and Afar regions.

In the Amhara region, more than 1.4 million people are internally displaced due to the ongoing conflict (The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ethiopia, 7 December 2021). As well, “more than 1.3 million people [are] in need of immediate emergency response and 376,000 people [are] displaced from 17 woredas” in the Afar region (The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ethiopia, 7 December 2021). According to the latest report of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), “an estimated 9.4 million people need food assistance across northern Ethiopia due to the ongoing conflict” (OCHA, 2 December 2021).

In November, humanitarian flights to Mekelle resumed on 23 November after the United Nations suspended its twice per week flights to Mekelle on 23 October (OCHA, 25 November 2021; Office of the Prime Minister Ethiopia, 30 November 2021). By the end of the month, “humanitarian access to the region slightly improved” (OCHA, 2 December 2021). In the last week of November, 160 trucks carrying humanitarian food reached the Tigray region and 353 trucks carrying humanitarian assistance items were heading to the Tigray region through Semera, Afar region (Office of the Prime Minister Ethiopia, 30 November 2021). By 7 December, 203 trucks had arrived in Tigray (Office of the Prime Minister of Ethiopia, 7 December 2021). According to the government, from July to October 2021, around 1,114 trucks carrying humanitarian assistance entered the Tigray region; only 322 trucks returned after delivering the humanitarian aid (Office of the Prime Minister Ethiopia, 30 November 2021).

In November, 27 demonstrations were held to denounce the TPLF, OLF-Shane, US intervention in Ethiopia, and perceived biased reporting on Ethiopia by the international media (see map below). These demonstrations were held in Gambella, Oromia, Somali, the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region (SNNPR), Sidama, Addis Ababa, and Dire Dawa. The highest number of protests were held in the Oromia region. In Addis Ababa, on 25 November 2021, around two thousand of the city’s residents gathered outside the US embassy in protest, accusing the US government of foreign intervention in Ethiopia and spreading false information. The group also marched to the British embassy (DW Amharic, 25 November 2021).

In the Oromia region, armed clashes and civilian attacks continued throughout the month. OLF-Shane clashed with ENDF, Oromia regional special forces, and Oromia militias in West Shewa, West Wollega, East Wollega, and Horo Guduru zones. At the beginning of the month, members of OLF-Shane were accused of abducting 70 people from Anger Gutin town in Gida Ayana woreda in the East Wollega zone. The abductions occurred amid heavy clashes between Oromo and Amhara communities in the area which have been ongoing for months. On 19 November, following an attack by unidentified gunmen on Amhara militiamen in Mettu Selassie, Amhara militias attacked Oromo civilians in Nono in the West Shewa zone, resulting in the deaths of at least 20 people. On 23 November, gunmen with suspected links to OLF-Shane ambushed and killed three officials in Mida Kegn woreda in the West Shewa zone. The deputy administrator of the woreda was also injured in the attack. A spokesperson for the group has denied that his forces were involved (BBC Amharic, 23 November 2021).

Similarly, armed clashes and civilian attacks continued in Benshangul/Gumuz region. Attacks by Gumuz armed groups and the Benshangul People’s Liberation Movement are common in the region. Government sources often claim that the militants are being supported by the TPLF. Additionally, last month, the head of the Metekel zone communication office, head of regional anti-insurgency forces, and the mayor of Gilgel Belles town were reportedly arrested by federal soldiers stationed at a command post in the Metekel zone under suspicion of having links with armed groups. Further, ENDF and Benshangul/Gumuz regional special forces clashed with an unidentified armed group affiliated with TPLF in Menge and Sherkole in the Asosa zone. On 11 November, the Ethiopian military, in a joint security operation with regional police forces, clashed with the Benshangul People’s Liberation Movement in Gemed Kebele in Sherkole woreda in the Asosa zone. Government forces claimed to have killed over 200 rebel militia members and rescued 19 people, including 12 women, abducted by the rebels (EBC, 12 November 2021). Fatalities could not be independently verified.

Several armed clashes near the border of Ethiopia and Sudan were also reported last month. On 19 November, Benshangul/Gumuz region special police forces clashed with a “TPLF affiliated armed group” in unspecified locations described as being “near the border with Sudan” (OBN, 19 November 2021). The police forces claimed to have killed an unspecified number of militants and captured armaments, including anti-tank mines. At the end of the month, the Sudanese government claimed that Sudan’s army and the ENDF and “Ethiopian militias” clashed at the borders of the two countries, reportedly leading to the deaths of at least 20 Sudanese soldiers (VOA, 27 November 2021; Bloomberg, 28 November 2021). The Ethiopian government denied this accusation and blamed the Sudanese government for assisting insurgents in attacking Ethiopia (ESAT, 27 November 2021). According to another report, the Samri group, which is affiliated with TPLF, clashed with ENDF, Amhara regional special forces, and Amhara militia in Delelo Kuter 6 and Tiha areas in Metema in the West Gondar zone in the Amhara region (ESAT, 27 November 2021). Reportedly, Sudanese soldiers were fighting Ethiopian forces alongside the Samri group (ESAT, 27 November 2021).

Finally, last month, the eleventh region of Ethiopia — the South West Ethiopia People’s region — was officially formed. On 30 September, residents in Konta Special woreda, West Omo zone, Bench Sheko zone, Dawro zone, and Sheka zone held a referendum in which the majority decided to form a new region of Ethiopia rather than continuing to be administered under SNNPR. The new region chose Bonga town as its capital city. Bench Sheko zone representatives disputed this decision as it was made without following the agreed-upon procedures for selecting a capital (ESAT, 20 November 2021; Ethiopia Insider, 18 November 2021).

Monthly Focus: United Front of Ethiopian Federalist and Confederalist Forces

On 5 November 2021, a coalition of nine anti-government factions meeting in Washington, DC formed an alliance called the “United Front of Ethiopian Federalist and Confederalist Forces” (The Guardian, 5 November 2021). According to representatives present at the meeting, the new coalition aims to “totally dismantle the existing government either by force or negotiation….then insert a transitional government” (Reuters, 5 November 2021).

Among the nine factions were two that had already formed an alliance, the TPLF and the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA), referred to by the government as the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF)-Shane (AP, 11 August 2021). The rest of the alliance is made up of smaller, less active fronts. As the name suggests, each group strives to champion the rights of their respective ethnic groups as part of a federalist/confederalist system in the face of what they describe as attempts to erase their respective culture, land, or identity.

For many familiar with Ethiopia’s history, the forming of an anti-government alliance made up of several ethnic “liberation fronts” was reminiscent of the united front which ultimately toppled the government of Mengistu Haile Mariam in 1991. The Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), a coalition of the TPLF, the Oromo Peoples’ Democratic Organization (OPDO), and the Ethiopian People’s Democratic Movement (EPDM), marched into Addis Ababa on 28 May 1991 and established a provisional administration on 1 June 1991 (The Guardian, 29 May 2021).

In the monthly focus below, we examine the information available about eight of the members of the United Front of Ethiopian Federalist and Confederalist Forces, concluding with an examination of the likelihood of the TPLF succeeding in maintaining this alliance. We conclude that it is unlikely that this alliance will be able to repeat Ethiopian history by threatening the capital, Addis Ababa.

Ultimately, upon examining both historical and recent events in Ethiopia, it is clear that this newly formed alliance has little capacity to actually threaten the federal government as they stand now. The main reason for this is that while the TPLF provides military heft to the coalition, its history of violence and repression has in many ways severed the relationship between these groups and their communities of support. This is especially true in Afar and Agaw areas. Furthermore, unlike the Derg regime, the current government led by Abiy enjoys popular support from around the country.

1. Afar Revolutionary Democratic Unity Front (ARDUF), represented by Muhammad Ibrahim

The ARDUF is based in the northern Afar region and has been active for several years. The organization was formed in 1993 as a coalition of three Afar organizations, including the Afar Revolutionary Democratic Unity Union (ARDUU), Afar Ummatah Demokrasiyyoh Focca (AUDF), and Afar Revolutionary Forces (ARF). Despite changing alliances several times, it has maintained its main goal of uniting all ethnic Afar people living across three countries (Ethiopia, Djibouti, and Eritrea) under a single flag (Yasin, Y. M., 2008). Prior to the ousting of the TPLF from the federal government in 2018, the ARDUF (sometimes called by its Afar abbreviation, UGUGUUMO), maintained a low-level insurgency against the TPLF-led EPRDF.

In 2007, AFDU leader chairman Mussa Ibrahim called the TPLF “the most repressive regime in the history of Ethiopia” (allafrica, 20 March 2007). In 2012, ARDUF was responsible for the abduction and subsequent death of several tourists in the Afar region during a raid against Ethiopian military forces (ARDUF Military Communique No 12, 12 January 2012). The second incident in 2017 left another tourist dead (BBC, 5 December 2021).

The ARDUF’s political position is complex in that it has both aligned itself with the regional government of Afar while at the same time opposing the federal government. Recently, militias loyal to the ARDUF were involved in a series of bloody ethnic-based clashes along the Somali/Afar border. During the runup to the national election in 2021, the conflict was centered around three kebeles inhabited by ethnic Somalis from the Issa clan. During these clashes, the ARDUF was aligned with forces from the Afar regional government and allegedly fought alongside Afar regional special forces, maintaining a position that Somali militias and special forces were facilitating the expansion of Somali settlements into Afar land. See EPO’s Afar-Somali Border Conflict page for more information. Protests by ethnic Somalis in July 2021 closed the Ethio-Djibouti highway, which TPLF forces are currently attempting to take (Reuters, 28 July 2021).

The ARDUF maintains other politically complex positions. Like other members of the newly-formed anti-government alliance, the ARDUF spent decades fighting an insurgency against the TPLF. Its current alliance with the group represents a political pivot that, evidence suggests, was not popular among the Afar population. Instead, the TPLF invasion of Afar in July 2021 appears to have galvanized support for the federal and regional governments. Government efforts to exploit anti-TPLF sentiment among the Afar population were successful and militias and regional special forces from Afar have played a major role in repulsing the TPLF from the region. It thus appears that the ARDUF’s recent signing of an alliance with the TPLF was neither popular nor successful.

The ARDUF has been unsuccessful in its attempts to capture public opinion in regard to the federal government and the TPLF. A statement in August 2021 blaming the ENDF for the death of at least a dozen people in a shelling incident that took place in Galikoma, Fanti-Rasu zone in the region was generally ignored while government narratives blaming TPLF forces for the incident have been amplified (Ayyaantuu, 9 August 2021). While the incident is still disputed, the TPLF’s decision to attack Ethiopian and Afar regional forces in the Afar region has resulted in building opposition to the group as conflict has destroyed infrastructure and upended lives through displacement and civilian casualties. ACLED records five anti-TPLF protests in the Afar region since July 2021.

In addition to complications related to local support, the ARDUF brings to the federalist coalition additional political headaches. The ARDUF’s goal in uniting all ethnic Afar would necessitate territorial arrangements with both Eritrea and Djibouti. The caliber that this type of diplomacy and military power would require for such a demand to be tolerated by either country is simply not something the new alliance could possibly entertain.

2. Agaw Democratic Movement, represented by Admassu Tsegaye

There is little information available about the Agaw Democratic Movement, nor are there any independent reports to shed light on their activity. Heavy fighting has taken place throughout the TPLF conflict in areas where the Agaw Democratic Movement is active (in both Wag Hamra and Agew Awi zone, Amhara region), involving militias that are almost certainly linked to the group.

The Agaw are a Cushitic-speaking people who reside primarily in Wag Hamra and Agew Awi zones of the Amhara region, parts of which have been under the control of the TPLF since July 2021. According to reports from both BBC Amharic and DW Amharic, residents of the Wag Hamra zone have suffered as a result of the conflict, with local officials reporting starvation and displacement as a result of the TPLF occupation (DW Amharic, 20 October 2021; BBC Amharic, 5 October 2021).

The registration of the Agaw Democratic Party was canceled on 23 December 2020 by the National Election Board of Ethiopia after the party failed a check on membership requirements (NEBE, 22 December 2021). The leader of the Agaw Democratic Movement in DC, Admassu Tsegaye, had attended an Unrepresented Nations and People’s Organization (UNPO) sponsored electoral debrief as a representative of the Agaw Human Rights Advocacy Group in July 2021. In a statement, he claimed that “Ag[a]ws have lost trust in the political system and feel excluded and marginalized post-elections” (UNPO, 1 July 2021).

On 26 April 2021, suspected TPLF associated militants likely linked to the Agaw Democratic Movement launched an attack against Amhara special forces in Nirak town (Wag Hamra, Amhara region), killing 11 people, including civilians. TPLF sources claim to have successfully taken control of a weapons store and gained provisions before leaving the town, while government communications claim that the Amhara regional special forces successfully repelled the attack. Additional battles fought near Abergele in August 2021 also likely involved Agaw militias (DW Amharic, 13 August 2021).

3. Benshangul People’s Liberation Movement (BPLM), represented by Yusuf Hamid Nasser

Benshangul/Gumz region continues to be one of the most violent locations in Ethiopia, partially due to the insurgency being waged by the BPLM. The area is inhabited by Gumuz, Shinasha, Amhara, Oromo, Agaw, and other ethnic groups. Gumuz, Berta, and Shinasha are identified as indigenous ethnic groups, while ethnic Amhara and Oromo from areas of Wollo were resettled into the fertile land in Benshangul/Gumuz region during a severe drought in 1984-1985, triggering immediate land conflicts.

Conflict in Benshangul/Gumuz region is deeply rooted and fundamentally difficult to solve. Indigenous groups accuse “highlanders” (Oromo, Amhara) of forcibly taking land and have responded violently. Metekel zone of Benshangul/Gumuz is one of the most consistently violent locations in the country. As such, on 23 January 2021, a command post was established by the government to stabilize the zone and establish sustainable peace. The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, which is disputed by Egypt and Sudan, is being constructed in this zone.

The BPLM signed a peace agreement with the EPRDF in 2012, agreeing to end armed struggle (ReliefWeb, 20 August 2012). The situation in Benshangul/Gumuz region has since deteriorated amid ethnic conflict, with some commanders of the group returning to armed conflict. In the leadup to the national election (which never occurred in Benshangul/Gumuz region due to ongoing instability), hundreds of BPLM politicians were arrested and held without trial (Ethiopia Insight, 10 September 2021).

In the context of widespread ethnic conflict throughout the region, the role of the BPLM is not entirely clear. Official sources continually refuse to identify parties of the ongoing conflict and instead label them “Gumuz Militias” or “TPLF-Agents.” On 6 July 2021, the Benshangul/Gumuz regional government announced that it had given a number of government positions to an unspecified “25 former members of an armed group” — of which certainly some were former BPLM operatives (Addis Standard, 5 July 2021).

Likely, those units actively engaged in insurgent activity in Benshangul/Gumuz region today are contingents of the original BPLM group loyal to local commanders who disagreed with the group’s decision to disarm in 2012. The group has become more active since the start of the conflict against the TPLF, and, as of September 2021, controlled significant amounts of territory within the region (DW Amharic, 24 September 2021).

The BPLM representative who signed the group into the alliance in Washington, DC, Yussuf Hamid Nasser, is a well-known individual. After leading the BPLM as president of the movement in 1986, he became part of the Ethiopian government after the TPLF-led EPRDF toppled the Mengistu Haile Mariam (Derg) government. In 1992, Yussuf was appointed the Ethiopian ambassador to Yemen (African Intelligence, 26 November 2021). He reportedly claimed political asylum in Yemen after Ethiopia’s 1995 elections pushed BPLM politicians to the periphery of the EPRDF.

The Ethiopian government regularly reports having conducted operations against insurgents in Benshangul/Gumuz region along the Sudanese border. The government has alleged that these groups receive training and arms in Sudan (EBC, 19 November 2021; EBC, 28 July 2021). The link between the BPLM and any Sudanese government officials is not confirmed.

4. Gambella People’s Liberation Army, signed by Okok Ojulu Okok

The Gambella People’s Liberation Army (GPLA) is a relatively new organization that was founded in October 2021 after the 2021 Ethiopian national elections. Citing electoral “irregularities and malpractices,” the group armed itself and announced it was dedicated to overthrowing the Gambella regional government (Ethiopia Autonomous Media, 31 October 2021).

The group, like others in the alliance, has “franchise” organizational issues. Shortly after the signing of the alliance in Washington, DC, the GPLA put out an announcement claiming that the representative who signed the agreement on behalf of the front was not even a member of GPLA (Gambella Liberation Front/Army, 17 November 2021). The government news outlet EBC announced on 18 November that it had accepted the surrender of several youths who had fought for the GPLA (EBC, 18 November 2021).

5. Global Kimant People Right and Justice Movement/Kimant Democratic Party (KDP)

The Kimant (standardized by ACLED as Qemant) are an ethnic group that resides in portions of the Amhara region, namely the Quara, Chilga, Lay Armachiho, Denbia, Metema, and Gondar Zuria woredas. A number of Qemant ethnonational movements exist, and their agitation for greater autonomy within the Amhara region often leads to violent conflict. In 2017, seven of eight kebeles inhabited by majority Qemants in the Amhara region voted to remain under the jurisdiction of the Amhara regional state during a referendum, dashing hopes of achieving any special zone status and greater autonomy at that time (Addis Standard, 7 February 2019).

Amhara regional authorities accuse the TPLF of backing violent Qemant ethno-nationalist movements, including the Kimant Democratic Party (KDP), by providing “weapons and money” (BBC, 19 May 2021). In turn, Qemant groups accuse Amhara ethno-nationalist youth movements, such as the Fano, of perpetrating the violence that targets Qemant families during periods of instability.

Violence has drastically increased since the removal of the TPLF from power and the rise of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed in 2018. Amnesty International estimates that 130 people were killed in intercommunal violence from January to October of 2019, which also displaced thousands (Amnesty International, 2020).

Clashes resumed again in April 2021, with fighting erupting after a KDP meeting in Aykel town turned violent. Federal troops have since established a military command post in the area (Addis Standard, 22 April 2021). In May 2021, NEBE canceled electoral activities in areas of the Amhara region where conflict between the KDP and Amhara forces was occurring (NEBE, 19 March 2021). Security incidents in areas surrounding Gondar city were commonplace throughout the spring and summer of 2021 (DW Amharic, 28 May 2021). An investigation by Al Jazeera revealed that thousands of ethnic Kimant have been displaced to Sudan as a result of conflict between Amhara regional special forces, militia, and fighters loyal to the KDP (Al Jazeera, 6 October 2021).

6. Oromo Liberation Front-Oromo Liberation Army (OLA), signed by Jaal Odaa

Following the TPLF, the OLA is the most active insurgency group in the alliance. ACLED records 201 organized political violence events involving OLA forces (currently coded as OLF-Shane) over the past year alone. OLA militants have established territorial links linked with both the TPLF and Gambella Liberation Front operatives (Oddaa Tarbii, 31 October 2021; Reuters, 1 November 2021).

The OLA is active in areas throughout the Oromia region and holds territory in rural areas across the West and Southern Oromia region. While the group poses a major security challenge to both the federal government and the Oromia regional administration, they do not yet control any major urban center in the region. See also the EPO’s West and Kellem Wollega conflict page.

Like other movements in the new United Front, the OLA suffers from issues regarding both internal organization and community support. The group, at its outset, was formed when the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) disarmed in 2018 at the invitation of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (The Reporter, 6 October 2021). During the course of its armed struggle against the government, the OLA has been accused of serious crimes against ethnic minorities in the Oromia region which leaders of the group deny.

The group’s decision to join an alliance with the TPLF has likewise been met with some skepticism. Most of the group’s younger fighters were members of the Qeerroo movement, which led a non-violent resistance movement against the TPLF from 2014 to 2018 and claims credit for placing Abiy in power. TPLF crackdowns against Oromo youth participating in these protests were often extremely violent and communities across Oromia hold ill feelings toward TPLF leaders.

OLA has been an armed wing of the OLF since its establishment and is commanded by the OLF central command unit called Shane council. While active across the Oromia region, the OLA does not have even a fraction of the fighting capacity possessed by the TPLF. The TPLF spent decades at the top seats of the Ethiopian government and amassed financial fortunes and weapons stockpiles. The OLF, which fell out with the TPLF in 1992, had no political power and led a struggling insurgent force opposing the TPLF until 2018. When the OLA split from the OLF after the OLF returned from exile and some OLA militants disarmed in 2018, they inherited little in terms of weapons or popular support. Analysis that suggests that the OLA is equal or comparable to the TPLF in fighting capacity is fundamentally flawed.

7. Sidama National Liberation Front (SNLF), signed by Tesfaye Wojago Hillo

The Sidama Liberation Movement was part of the EPRDF transitional government as established by the TPLF in 1991. Two seats were allocated for SLM at the time (Addis Standard, 3 July 2021). The organization’s name was changed to the Sidama National Liberation Front (SNLF) in 1999 (Sidama National Liberation Front).

The SNLF has been inactive throughout the 2018-2021 period except to issue a few statements declaring support for the TPLF and denouncing forced conscription of Sidamo youth into the ENDF and Sidama special police (Tigray Media House, 15 July 2021).

Sidama was officially granted regional status on 18 June 2020 after 98% of its inhabitants voted in favor of leaving the SNNPR to become Ethiopia’s 10th regional state (AfricaNews, 23 November 2019). In doing so, the Sidama regional government loyal to Ethiopia’s governing Prosperity Party undercuts the SNLF’s stated goals of Sidama people’s national self-determination. As such, the SNLF is neither well known nor well developed even among its own community of support.

The Ethiopian government recently reported the arrest of several militants with suspected links to the TPLF or OLA in Hawassa, Sidama region on 13 November (EBC, 13 November 2021). It is unknown if these operatives were from the SNLF.

8. Somali State Resistance, representative Mahamud Ugas

The Somali State Resistance, as understood by local experts in the Somali region, did not exist prior to the signing ceremony in Washington, DC. The representative Mahamud Ugas served as Regional Minister of Planning and Economic Development from 1991 until 1995. From 1995 until 2000, Ugas worked as a consultant and field researcher for various humanitarian organizations. According to his biography, Mahamud left Ethiopia in 2000 and sought political asylum in Canada (Mahamud Ugas, Academia.edu). Neither Mohamud Ugas nor the Somali State Resistance has any official links to the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF), although it is likely that the ONLF is involved in some way. As well, Mohamud Ugas reportedly attended the 2012 Nairobi peace talks between the government and the then ONLF insurgency as a representative from the Ogaden Human Rights Committee (Tobais Hagmann, 2014).

Like the AFDU, Somali State Resistance will struggle to convince the Somali population (especially those in Ogadania), that aligning themselves with the TPLF is a good idea. As Ugas well knows, the TPLF has a long history of abuse in the Somali region, and decades of resentment will not be forgotten simply by the forging of a new alliance. Whether or not the Somali State Resistance is simply a front for the ONLF, or entirely a new organization built upon the political ambition to create space outside of the restrictions of the ruling Prosperity Party party remains to be seen.

Conclusion: The Tigray People’s Liberation Front’s Chances of Repeating History

With both experience and capacity that far outstrip the other member organizations, the TPLF holds significant amounts of territory and can actively govern locations under their control. The TPLF’s position within this alliance is clearly the organizer and provider, as there is not much that the other organizations (beyond the OLA) can realistically contribute.

The TPLF’s past, however, is extremely damaging and even these paper alliances are fragile. While the TPLF was able to overthrow the government of Mengistu Haile Mariam in 1991, their ability to overthrow the central government again is now hampered by their poor record of governance. There are likewise other factors to consider.

When the TPLF entered Addis Ababa in 1991, they overthrew a regime that was “deeply unpopular” (The Conversation, 21 November 2021). The same cannot be said about Abiy Ahmed, who, despite having many enemies throughout the state due to his heavy-handed behaviour, enjoys wide support from large swaths of the population. Secondly, each of the organizations described above has deeply rooted problems that contribute to its fragility and vulnerability to government attacks.

This is not to say that the government’s own Prosperity Party is not beyond its own undoing. Heavy-handed behavior through arrests and violence against civilians and opposition politicians will have its price one day in the future. Furthermore, the growing power of Ethiopia’s regional special forces loyal to the administration of each regional state is a dangerous phenomenon that could result in violence beyond the federal government’s ability to control.

More than anything, however, the anti-government alliance group members are contending with overwhelming violence wrought by the TPLF against their own communities, a factor that is too significant to ignore. In the Afar region, TPLF forces have left a wide trail of destruction only to retreat backward and provide little to the suffering civilians. Reports issued recently suggest that TPLF fighters in the Amhara region have engaged in the exact type of behaviour that TPLF leaders accused the ENDF and Eritrean forces of last year at the outset of the conflict (HRW, 9 December 2021). Oromo Liberation Front Chairperson Dawud Ibsa has called on the TPLF to halt its advance toward the Oromia region (DW Amharic, 6 November 2021). While some may sympathize with political ideologies of federalism or advocate for ethnic autonomy, there is growing anger against the TPLF that is impossible to ignore and has damaged the legitimacy of these constituent groups as they fail to represent the sentiments of the communities with which they are affiliated.

The events of 1991 are not likely to reoccur. The United Front of Ethiopian Federalist and Confederalist Forces differs in many fundamental ways from the EPRDF and contains little of its capacity. It has been thrown together with little consideration for Ethiopia’s troubled past. Until the government addresses the country’s issues in a genuinely inclusive and dignified way, however, violence will continue to be seen as the means for negotiating one’s way into Ethiopia’s political future.