General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the head of Sudan’s ruling Sovereign Council, dispatched over 6,000 soldiers to the Ethiopian border at the start of the war in Tigray region as part of an agreement reached on 1 November 2020. The agreement stipulated that Sudan would close its borders “to prevent border infiltration to and from Sudan by an armed party,” referring to the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF).1Africa Confidential, ‘Abiy risks more war,’ 21 January 2021; Tghat, ‘The war on Tigray: The support and involvement of the United States, Amhara, Eritrea, Sudan, Djibouti, Somalia and UAE,’ 17 January 2021 These deployments placed Sudanese soldiers in an area of the border that has been historically contested. The contested border area runs along the international boundary between Gedaref state in Sudan, and Amhara and Tigray regions in Ethiopia. Negotiations in 2008 between the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front-led government and the Sudanese government legally designated the land known as al-Fashaga triangle as Sudanese territory, but specified that Amhara farmers would be allowed to continue farming there.2Asharq Al-Awsat, ‘Al-Fashqa Returns to Sudanese Sovereignty After Agreement With Ethiopia,’ 12 April 2020 Amid periodic clashes and attacks in the area since 2014, the arrangement was finally dissolved with the deployment of Sudanese troops in November 2020. These forces have been accused of driving out Amhara farmers – and Tigrayan farmers in northern areas of al-Fashaga – after Amhara forces re-deployed to assist the federal government in the war against the TPLF in northern Tigray region.3Amhara Communications, ‘A statement issued by Mr. Dessalen, the chief administrator of West Gondar Zone, regarding the current border situation between Ethiopia and Sudan,’ 27 December 2020 Amhara regional militias and special forces (Liyu Police) have since responded to the displacement of ethnic Amharas from these areas, attacking Sudanese forces in areas inhabited by Amhara farmers since the mid-1990s (for more, see Red Lines: Upheaval and Containment in the Horn of Africa).

These actions have placed Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed in a difficult position. On the one hand, Abiy depends on Amhara militias to maintain positions against any potential resurgence of the TPLF to the north. On the other hand, he can hardly afford an international conflict that would certainly involve other actors like Egypt, given contestations over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

It is likely that the leadership of the Sudanese army is utilizing the conflict for internal political gain, rather than being invested – as it claims – in the actual matter of land ownership.4Middle East Eye, ‘Sudan launches assault on Ethiopia after alleged executions,’ 28 June 2022 While this would suggest that neither Khartoum nor Addis has an interest in escalating the fighting, there is a risk that localized conflict over the valuable farming ground could generate its own momentum as factions on both the Sudanese and Ethiopian sides continue to have political incentives to keep the conflict unresolved, this dynamic could draw in armed actors. The support of hardline Amhara nationalists and Amhara militiamen – including Fano – has the potential to keep the conflict burning, even if the federal government disapproves, and with unpredictable consequences.

The conflict was primarily being fought between infantry from the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) together with SAF ‘reservists’ known as the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) — that appear to be paramilitaries mobilized from the area — and infantry from the Amhara regional special forces often operating alongside local Amhara militias. Militiamen who work with the Amhara regional special forces are typically part of the legitimate, semi-regular militias that operate at the kebele level, and form the lowest rung of the Ethiopian security ladder.5Bruce Baker, ‘Hybridity in policing: the case of Ethiopia,’ 27 May 2013 In 2022, There have been reports of shelling – probably using mortars by the SAF and Ethiopian security forces – but no verified accounts of strikes by helicopters or aircraft. However, due to the armed conflict between the SAF and RSF in Sudan and the reintegration of regional special forces into various security sectors in Ethiopia in April, only local militias and paramilitaries might be involved in future conflicts.

On the other hand, criminal and vigilante militias also operate from Amhara-occupied regions. They are likely to be involved in the majority of abductions, cattle raids, and attacks on Sudanese civilians and farmers in the areas surrounding Gallabat town, around the southern edges of the disputed area. These different types of militia groups are often conflated together, or described as Shifta.6Agence France Press, ‘What is the truth about the attack launched by “Ethiopian forces” on the Al-Fashqa border area in Sudan?,’ 28 April 2023

External media coverage has tended to conflate the Amhara regional special forces with federal soldiers from the Ethiopian National Defence Force (ENDF). There is some evidence to suggest that the ENDF has been involved in the conflict, although its engagement is limited. It is likely that it has had a peripheral role in the actual fighting. There are few specific or verifiable accounts indicating the ENDF has crossed the internationally recognized boundary into Sudan after hostilities began; For example, Sudanese news reported a prisoner exchange, in which ENDF soldiers were handed over. However, it is possible that Sudanese news mistook the former Amhara regional special forces for ENDF soldiers.7Sudan Tribune, ‘Sudan to hand over 60 Ethiopian militiamen, soldiers,’ 10 April 2021 There are frequent claims of troop build-ups on both sides of the border, though lacking precise information on the actual size of these forces. In some cases, troop deployments may not have been directly related to the border fighting, but instead linked to military operations in Western Tigray zone. Between November 2020 and the end of 2022, the deployments could also be efforts by Amhara regional special forces to forcibly relocate Tigrayan civilians to central Tigray.8Al Jazeera, ‘Ethiopia warns Sudan over military build-up amid border tensions,’ 12 January 2021

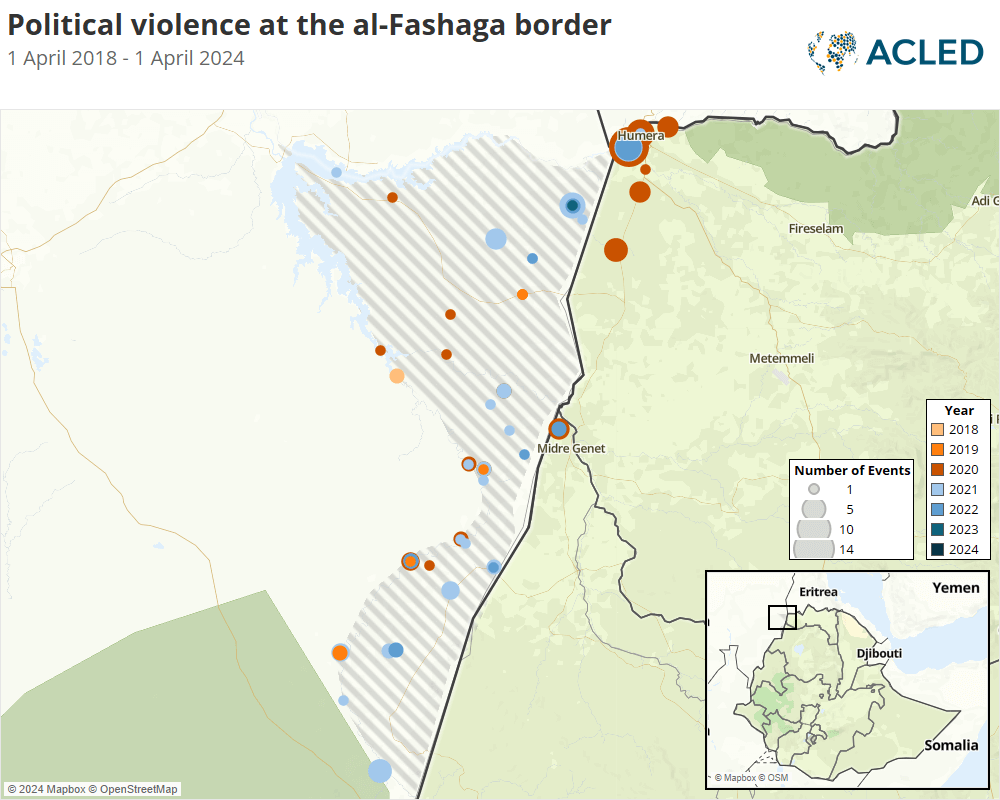

It is unclear how many have been killed and wounded in the conflict. When casualties are reported, they tend to be low (usually in single digits), and such reports are infrequent. ACLED records at least 100 reported fatalities in al-Fashaga area from April 2018 to April 2023. In early 2021, Ethiopia claimed that many Amhara civilians were forcibly displaced after the SAF first entered the disputed areas in November 2020.9Max Bearak, ‘A border war looms between Sudan and Ethiopia as Tigray conflict sends ripples through region,’ Washington Post 19 March 2021

In 2021, fighting clustered in the Barakhat area of ‘Greater Fashaga,’ which corresponds to areas of al-Fashaga locality east of the Atbara river (see map below). At the time, the area was described as the last Ethiopian stronghold in the locality, following a string of territorial acquisitions by the SAF. Meanwhile, in ‘Lesser Fashaga’ to the south, fighting has been reported in several locations, with cross-border shelling near Abdel-Rafi on the Ethiopia side. Although military clashes are clustered in the northern half of al-Fashaga Triangle, there are sporadic reports of often ransom-motivated attacks and abductions of Sudanese farmers in Eastern el-Gallabat and Basundah localities to the south. It should be noted, however, that these attacks have preceded the current conflict by several years. There is increasing discontent over these attacks by Sudanese residents of the area; in late January 2021, they blocked the border at Gallabat town to demonstrate against the abductions and killings.

During the summer of 2022, tensions between the Sudanese and Ethiopian governments escalated again, as the government of Sudan accused the ENDF of killing seven captive members of the SAF and one civilian.10BBC Amharic, ‘It was reported that Sudan has recalled its ambassador in Ethiopia to Khartoum,’ 27 June 2022 Most recently, in the spring of 2023, Sudanese media sources claimed that clashes again reignited in the area following an attack by Ethiopian forces looking to take advantage of wider instability in Sudan.11Asharq Al-Awsat, ‘Is Ethiopia taking advantage of Sudan’s unrest to resolve the “border dispute?,”’ 21 April 2023 Prime Minister Abiy immediately dismissed the claim as false and warned that “parties” were transmitting false claims to incite conflict between the two countries.12Facebook @Abiy Ahmed Ali, 20 April 2023

Belligerent rhetoric from elements of the political establishment in Khartoum and Addis Ababa has encouraged fears of an intensification of the conflict, amid mutual accusations of third-party involvement.13Africa Confidential, ‘Border ructions escalate over Al Fashqa,’ 22 February 2021

This conflict profile was last updated on 05/08/2024.