April-May at a Glance

Vital Stats

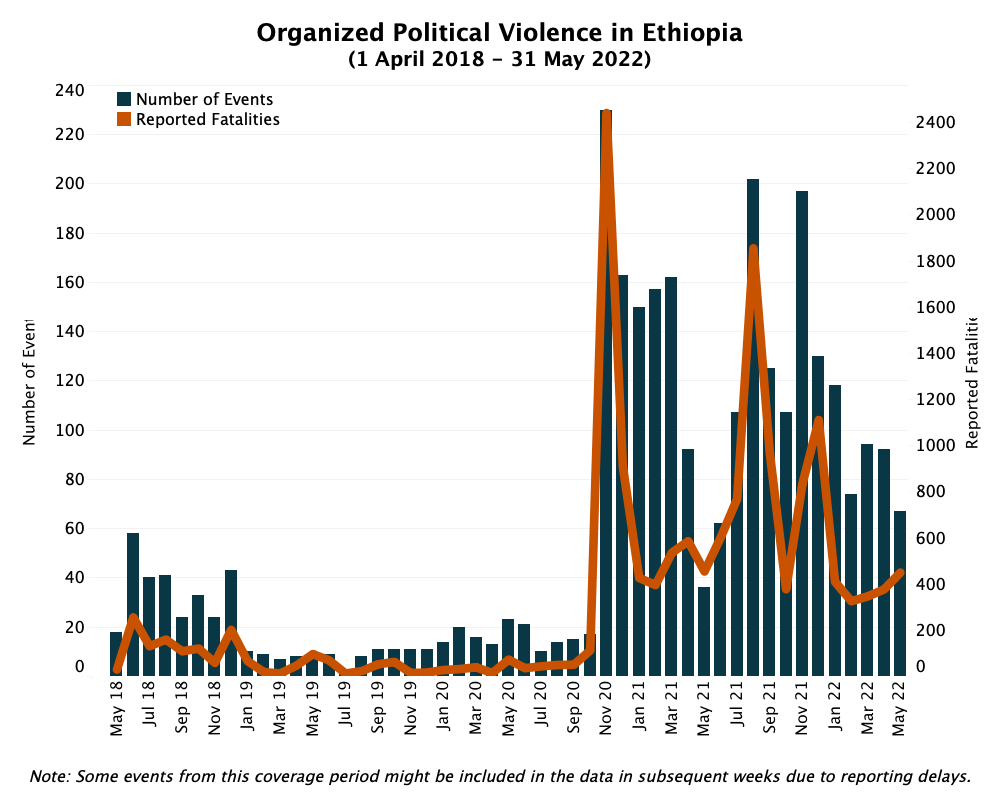

- ACLED records 92 organized political violence events and 377 reported fatalities in April; ACLED records 67 organized political violence events and 450 reported fatalities in May.

- In April, Oromia region had the highest number of reported fatalities due to organized political violence with 309 reported fatalities. Amhara region followed with 37 reported fatalities.

- In May, Oromia region had the highest number of reported fatalities due to organized political violence with 287 reported fatalities. Tigray region followed with 121 reported fatalities.

- In April, the most common event type was battles with 61 events and 251 fatalities reported. Similarly, in May the most common event type was battles with 34 events and 368 fatalities reported.

Vital Trends

- In April and May, the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF)-Shane continued to clash with the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF), Oromia regional special forces, and Oromia militias in different parts of Oromia region.

- In May, armed clashes between the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and Eritrean Defense Force (EDF), and shellings by the EDF were recorded in Tigray region. No events involving the TPLF were reported in April.

- In April, armed clashes and attacks against civilians erupted in Derashe special woreda in Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region (SNNPR).

- In April, political disorder involving religious groups escalated. The same month, ACLED registered the highest number of riot events since June 2020.

- Mass arrests were recorded in several regions in the country due to the government’s “law enforcement” operations, with the highest number of arrests reported in Amhara region in May.

In This Report

- April-May Situation Summary

- Monthly Focus: Religious Violence in Ethiopia

April-May Situation Summary

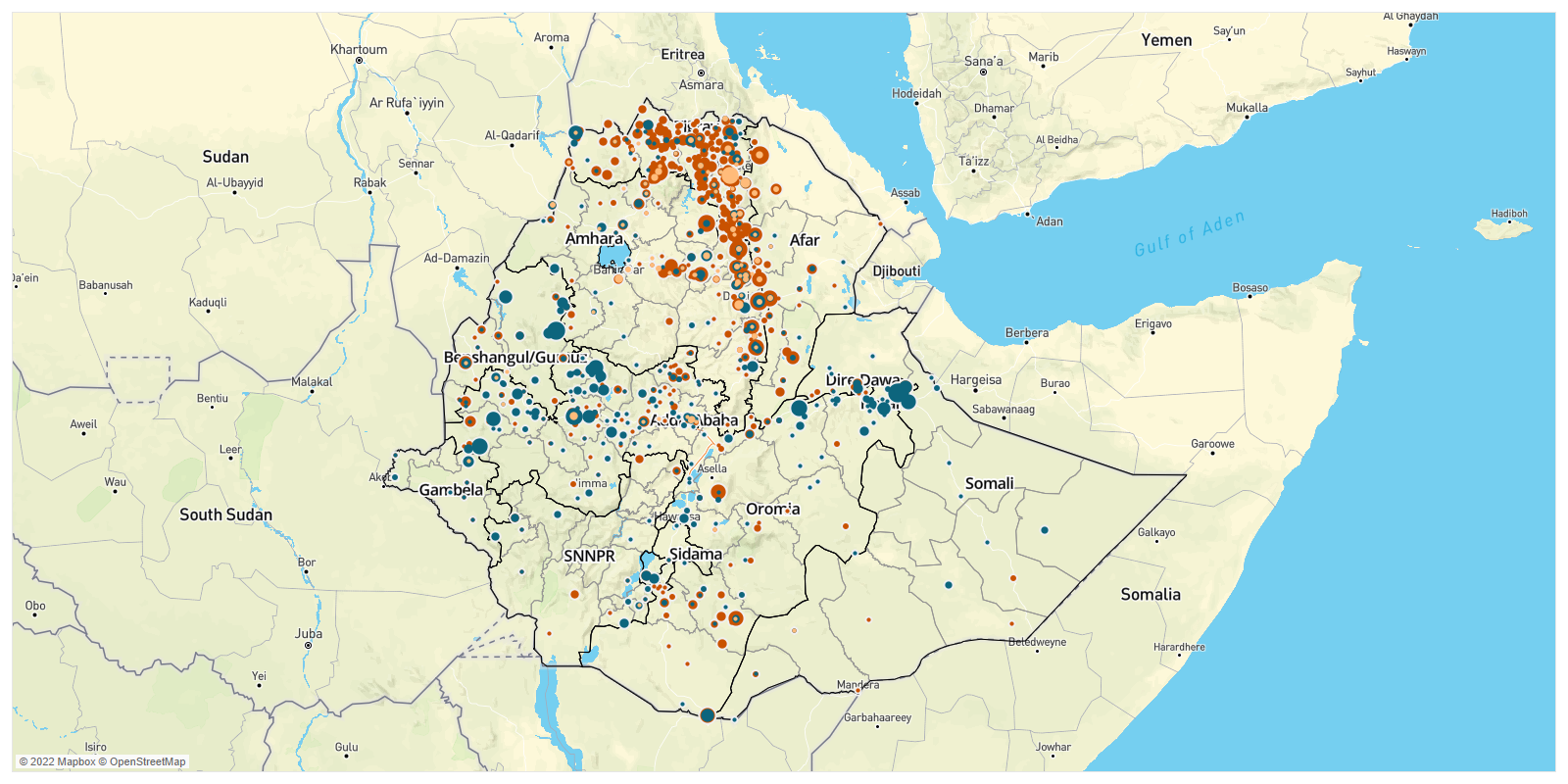

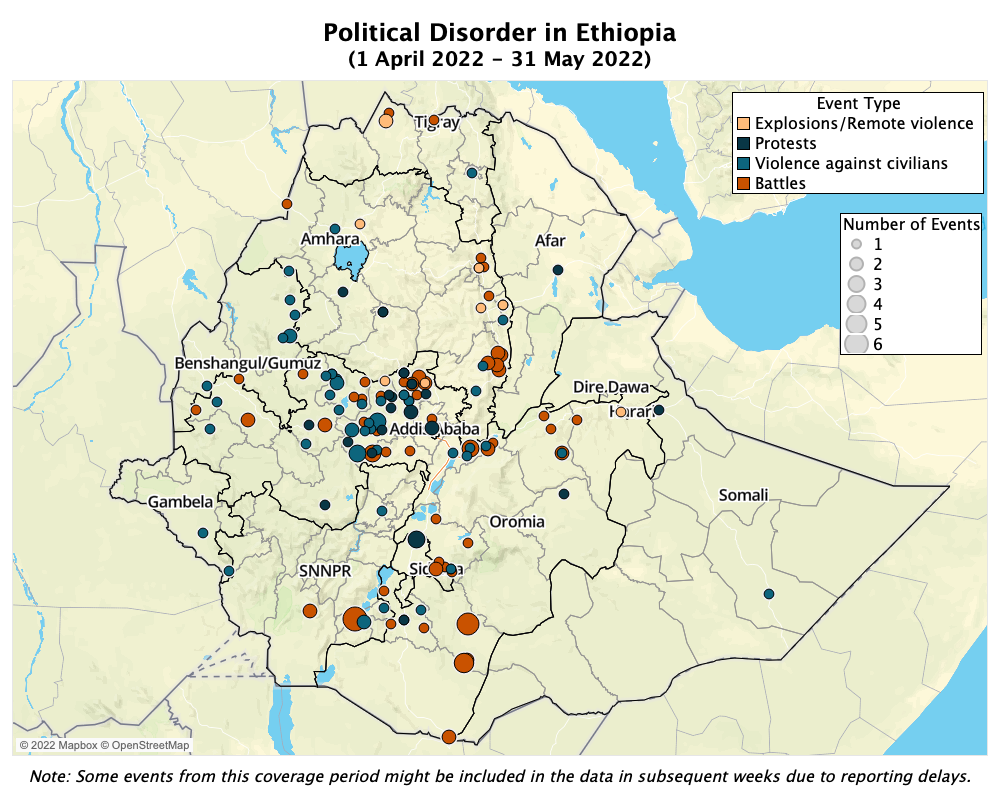

In both April and May, the battles event type had the highest number of events, with the majority of these events – 37 out of 61 in April and 25 out of 34 in May – recorded in Oromia region (see map below). Most of the battle events occurred between the OLF-Shane, ENDF, and Oromia regional special forces. In April, ACLED recorded 35 battle events between OLF-Shane and government forces. In May, all recorded 25 battle events in Oromia region were between OLF-Shane and government forces across various zones. In both months, armed clash events were recorded in East Shewa, Guji, North Shewa, Horo Guduru, South West Shewa, West Arsi, West Guji, and West Shewa zones. In Borena and East and West Wollega zones, armed clash events were only recorded in April, while in East Hararge, Finfine Special, and West Hararge zones, they were only recorded in May.

Armed clash events involving the OLF-Shane were also recorded outside Oromia region. On 26 April, the ENDF clashed with OLF-Shane in Korka, Albasa, Sunbosre, Geshe, Gongo, Chele, and Julayu kebeles in Dibate woreda in Metekel zone in Benshangul/Gumuz region, taking control of these areas shortly after. On 17 and 18 April, Fano and Amhara ethnic militias clashed with the OLF-Shane and Oromo ethnic militias in areas bordering North Shewa and Oromia special zones in Amhara region. In North Shewa zone, armed clashes were recorded in Zembo, Addis Alem, and Negeso kebeles in Efratana Gidem woreda, and Kewet in Menze Mama Midir woreda. In Oromia special zone, fighting occurred in Wesen Kurkur, Mute Facha, and Tikure Wadawo in Jilye Tumuga woreda. At least 20 people were killed and 48 others were injured as a result of fighting in these woredas (DW Amharic, 21 April 2022). Amhara regional special forces and the federal police were involved to control the armed clashes. At least two members of Amhara regional special forces were killed by one of the warring parties during an operation to control the clashes (BBC Amharic, 21 April 2022).

A higher number of violence against civilians event type was recorded in Oromia region in both April and May compared to previous months. In April, ACLED recorded 27 violence against civilians events in Ethiopia, with 17 recorded in Oromia region. In May, 28 violence against civilians events were recorded in Ethiopia, with 17 of these events recorded in Oromia region. The ENDF, federal police, Oromia regional special forces, Amhara ethnic militias, Fano militias, and the OLF-Shane were reportedly involved in these events in Oromia region. ACLED data demonstrate an increase in extrajudicial killings by government forces in April and May. Government forces – i.e., ENDF, federal police, and Oromia regional special forces – were implicated in 10 of the 17 recorded violence against civilians events in April, and 11 of the 17 recorded violence against civilians events in May. This is an increase from March when ACLED recorded only three extrajudicial killings involving government forces in West Shewa zone. Victims were either accused of being OLF-Shane members, having links with the OLF-Shane, or hiding members of the group. In both months, the highest number of fatalities due to violence against civilians events were recorded in West Shewa zone. In addition, in April, ENDF and Oromia regional special forces arrested over 300 civilians in Boji in Gudetu Kondole woreda in West Wollega zone over suspicion of having links with OLF-Shane rebels.

Violence against civilians events where the OLF-Shane targeted civilians in Oromia region decreased in April and May compared to March. In April, one such event was recorded, while two were recorded in May. In April, the OLF-Shane killed eight members of one family, abducted an unidentified number of children, and burned and looted houses in Meneyo and Dire kebeles in Dera woreda in North Shewa zone in Amhara region. In May, the OLF-Shane was implicated in two violence against civilians events in Amaro woreda in SNNPR and Bati woreda in Oromia special zone in Amhara region.

In the meantime, Amhara ethnic militias and Fano militias continued to attack civilians in Oromia region. In April, ACLED recorded six violence against civilians events involving these actors in Horo Guduru Wollega, West Shewa, and East Shewa zones. In May, four violence against civilians events involving Fano militias were recorded in Horo Guduru Wollega zone.

In the last two months, ACLED recorded 23 protest events in Ethiopia – 16 protest events in April and eight in May. Most of these protests – nine in April and six in May – were held in Oromia region. Seven of the nine protests in April and all protests in May were peaceful protests against the OLF-Shane. Two protest events in April were about other issues. The majority of the protests against the OLF-Shane were held in West Shewa zone. In this zone, protests were recorded in Awara and Bake Kelate towns in Abuna Ginde Beret woreda, Seyo in Dano woreda, Inchini in Adda Berga woreda, Shikute town in Jeldu woreda, and Ambo town. Similar protests were also held in Gohatsion in North Shewa zone, Nekemte town in East Wollega zone, Gebre Guracha and Wabe towns in North Shewa zone, and Bule Hora town in West Guji zone. On 5 April, residents of Beltu town in Lege Hida woreda in East Bale zone gathered in protest against electric power disruption in their town. Oromia regional special forces opened fire, beat, and wounded an unknown number of protesters to disperse the gathering. Over 30 people accused of organizing the protest were also arrested. On 29 April, Muslims gathered in Jimma town to denounce attacks on Muslims in Gonder city. These religion-based attacks and the unrest that followed the attacks are discussed in detail in the Monthly Focus section.

Elsewhere, intercommunal violence between Oromo and Sidama communities erupted on 3 April in Halela and Sucha kebeles in Chiri woreda in Sidama region and Shambel and Wero kebeles in West Arsi zone in Oromia region, resulting in four people getting killed and 15 others injured. The clashes occurred after an unidentified armed group killed a local Sidama elder in Halela kebele in Chiri woreda in Sidama region (Ethiopia Insider, 5 April 2022). In May, Oromo and Sidama ethnic militias clashed in Hamesho Borena kebele in Bensa woreda and in Sangota kebele in Bura woreda, resulting in the deaths of six people and the injuring of 17 others.

In SNNPR, several riot and armed clash events related to demands for administrative status change were recorded. On 6 April, a group of Ari ethnic group members, demanding the establishment of a separate zonal administration for their ethnic group, attacked civilians and burned some houses in Ari woreda and Jinka town in South Omo zone. At least one person was killed during the unrest and 25 people were wounded. Some residents speculated that the reason behind the violence might be the fact that the South Omo Zone Council failed to put demands by the Ari ethnic group as an agenda item for discussion during its session the previous week. The zone administration officials apologized for this mistake and tried to calm the situation by holding discussions with the community (Tikvah-Family, 10 April 2022). However, from 9 to 11 April, Ari youths continued to attack and burn government buildings, residential housing, and shops in and around Gazer, Tolta, and Matser areas of Jinka town. As a result, a curfew was declared on 10 April and the ENDF and federal police were called to control the violence (Bisrat Radio, 11 April 2022). In April, around 842 people, including four police officers, were arrested under suspicion of participating in the violence. In May, unidentified ethnic groups clashed for an unknown reason in Selam Algo woreda in South Omo zone in SNNPR. An unidentified number of people were killed and internally displaced due to the clashes.

During the last week of April, riot and armed clash events were also recorded in Derashe special woreda in SNNPR. The armed clashes continued in May. As a result, all public and private institutions were closed for over a week. On 26 April, Gumayde militiamen, who were allegedly supported by armed groups from Derashe special woreda, kidnapped eight Indian tourists and an unidentified number of Ethiopians traveling from Arba Minch town to Jinka after attacking their vehicle, the driver, and a member of the ENDF in Holte kebele. An unknown number of federal police officers and SNNP regional special forces were killed in Holte kebele as they entered the area to rescue the kidnapped tourists. The abductees were released when government forces entered the woreda (DW Amharic, 28 April 2022). The following day, Gumayde militias clashed with SNNP regional special forces and kebele militias in Gato kebele and Gidole town in Derashe special woreda. These clashes resulted in an unknown number of reported fatalities from both sides. Hundreds of civilian homes were destroyed, and residents were forced to evacuate Gato kebele. The militants also burned the homes of Derashe special woreda government officials in Gidole town. This forced the officials to go into hiding. Armed clashes between Gidole and Konso ethnic militias were also recorded on 27 and 29 April in Gidole town. Further, on 30 April, Derashe and Konso ethnic militias clashed in Derashe special woreda. The same day, a local administrator was killed by rioters in Busta Killa kebele in the woreda. Rioters accused him of not passing the people’s request to form their own administration level to the higher officials. The administrator had been hiding in a forest near Busta Killa kebele since 27 April due to ongoing unrest in Derashe special woreda.

The armed clashes continued in May when ENDF, federal police, and SNNP regional special forces fought against Derashe ethnic militias in Hataya and Selele rural villages near Gidole town on 9 May. Around 316 people accused of being involved in the unrest and armed clashes in Derashe special woreda were arrested last month. Derashe is one of the woredas in SNNPR where a demand for the establishment of a zonal administration is being raised (see EPO’s Conflict Profile page Segen Area Peoples Zone Conflict for more details).

In Konso zone, on 11 and 12 May, an unidentified armed group attacked civilians in Becho kebele in Gumayde in Segen Zuria woreda and killed at least one civilian. The group burned houses and a church. An unidentified number of people were displaced due to these attacks.

Three peaceful protest events at the administration center of SNNPR, which is located in Hawasa city in Sidama region, were recorded in April. Mareko ethnic group members from Gurage zone held a peaceful demonstration to demand that Mareko woreda be recognized as a special woreda, separated from Gurage zone. Sebatbet Dobi Kistane ethnic group members from Gurage zone also held a peaceful protest, demanding the establishment of a separate woreda for their ethnic group. Around the same time, the Koore ethnic group gathered in front of the SNNPR president’s office in Hawasa city and peacefully demanded from the government to put an end to “atrocities against Koore farmers in Amaro woreda by OLF-Shane rebels” (VOA Amharic, 13 April 2022).

In Amhara region, two significant trends dominated the months of April and May. As discussed in detail in the Monthly Focus section, political disorder involving religious groups escalated in April. In May, the regional government began a “law enforcement” operation in the region. Consequently, tensions between Fano militias, Amhara ethno-nationalists, and the government increased throughout the month (see EPO Weekly: 14-20 May 2022 and EPO Weekly: 21-27 May 2022 for more details). According to the regional government, a “law enforcement operation” was necessary, given the recent spate of smuggling incidents, shootings, and interference with court decisions in the region (Amhara Media Corporation, 18 May 2022; Amhara media Corporation, 21 May 2022). As part of the operation, over 4,500 people, including journalists and the former leader of Amhara regional special forces, were arrested (Amhara Media Corporation, 23 May 2022).

Three armed clash events involving Fano militias, ENDF, and Amhara regional special forces were recorded in April before the beginning of the law enforcement operation in the region. On 10 April, ENDF and Fano militia members exchanged fire in Woldiya town in North Wello zone when Fano militiamen from surrounding areas tried to enter the town following rumors that a Fano militia leader was arrested. A militia member and a priest were killed during the clashes. The two groups also fought in Gobeye and Robit in North Wello zone on the same day. There were no reported casualties in these areas.

Shortly after Amhara regional authorities issued a decree in mid-May announcing that all weapons must be registered, three armed clash events were recorded in the region (Amhara Media Corporation, 16 May 2022). Clashes between government forces and Fano militia members were recorded in Motta in East Gojam zone. Two other armed confrontations between government forces and an unidentified armed group were also registered in Metema woreda in West Gondar zone and Bistima town in Were Babu woreda in South Wello zone. In Bistima, the unidentified armed group clashed with security forces when they attempted to forcefully release a detainee who had been arrested on accusation of conspiring to incite religious unrest in the town. Four people were killed, and 11 others were injured.

Meanwhile, demonstrations were held in Motta town in East Gojam zone and Marawi town in West Gojam zone to demand the release of imprisoned youth. ENDF and Amhara regional special forces fired live bullets on demonstrators, killing and injuring an unknown number of people. On 29 May, members of an armed group, claimed by the police to be a Fano militia group, threw a grenade at police officers around Kela in Banbewa Weha area in Dessie town in South Wello zone. Three police officers were reportedly injured. Witnesses denied this claim and instead insisted that one police officer accidentally shot himself and another police officer after a group of Fano militia gathered in the area to demand the release of arrested Fano members.

In Benshangul/Gumuz region, violence against civilians events involving security forces were recorded in both April and May. From 10 to 12 April, the ENDF, Amhara ethnic militias, and Amhara regional special forces reportedly killed an unknown number of ethnic Gumuz civilians in Godorare village in Bulen woreda, Dilsambe and Mender 3 in Dangura woreda, and Oshingi and Yekita villages in Madira woreda in Metekel zone. Meanwhile, according to the Dangur woreda command post, 247 members of the Gumuz People’s Democratic Movement (GPDM) had peacefully surrendered to government security forces by mid-April (Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation, 15 April 2022). In May, the ENDF shot and killed two people in Gipho kebele in Dibate woreda. One of the victims was accused of being a member of the OLF-Shane, while the reason for the killing of the second victim is unknown. Last month, ENDF and Benshangul/Gumuz regional special forces arrested over 300 people, including an Oromo Abbaa Gadaa (Oromo traditional leader), in Galesa kebele and its surrounding areas in Dibate woreda over suspicion of having links with the OLF-Shane. Out of 300 arrested people, 180 were released a week later (DW Amharic, 5 May 2022).

Elsewhere, in Harari region, an unidentified group threw a grenade at Yod hotel in Nefetegna Sefer in Shenkor woreda in Harar city on 24 April, injuring eight people. In Gambela region, on 21 May, an unidentified armed group attacked the Ukugo refugee camp and opened gunfire on refugees living in the camp near Dimma town in Agnewak zone and killed four people. The same day, an unidentified armed group attacked civilians in Merkes kebele and shot and killed two people. It is not clear whether the attackers were the same armed group.

In April, two attacks were reported by armed actors from neighboring countries. Around 13 April, Turkana ethnic militiamen from Kenya reportedly shot and killed an Ethiopian government official (The Standard, 13 April 2022). The exact location of this incident is unknown but was reported to have occurred on the Kenyan side of the border. On 14 April, Marehan clan militia members from neighboring Somalia attacked civilian pastoralists from Maqabul-Muse Gumcadle sub-clan group and killed five people near Caleen town in Korahe zone in Somali region. The reason for the attack is unknown, but the two groups had also clashed due to land disputes on 2 March.

After months of armed clashes between Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) forces, Afar regional special forces, and Afar militias in Kilbati Rasu-Zone 2 in Afar region, no armed clashes involving the TPLF were reported in April. In May, however, two armed clash events between the TPLF and Eritrean Defense Forces (EDF) were recorded in Rama in Central Tigray zone, and western part of Adi Awala in North Western Tigray zone. Furthermore, On 28 and 29 May, the EDF fired multiple rounds of artillery into areas held by the TPLF, striking a school hosting internally displaced persons (IDPs) and destroying houses in Sheraro town in North Western Tigray zone (Reuters, 31 May 2022). A 14-year-old girl was killed, and 18 people were injured due to the shellings.

Monthly Focus: Religious Violence in Ethiopia

Ethiopia has a long and rich religious heritage and is often celebrated as an example of peaceful interfaith coexistence. As an important location to both early Christianity and Islam, the country is home to hundreds of sites considered sacred to various faiths. Despite this, conflict throughout Ethiopia over the past two years has been devastating to both the religious places Ethiopians consider sacred and to the societal fabric that holds the country’s religious communities together. While religious conflicts have occurred periodically in Ethiopia, the pressures facing religious communities during today’s period of intensified political competition mark a new set of challenges for the Ethiopian religious society. This in turn has led to more frequent religious conflicts.

This monthly focus is written as a response to and continuation of the article written by Terje Østebø, a renowned expert on religion in Ethiopia. In his analysis as published by Addis Standard shortly after a spate of violence in October 2019, Professor Østebø argues that the religious violence occurring in Ethiopia post-political change in 2018 was a “new development” and explores whether or not “religion [was] emerging as a more explicit conflictual factor?” (Addis Standard, 6 November 2019).

In this article, we use ACLED data records of political disorder to analyze the recent spate of religious violence. We agree with the conclusions made by Professor Østebø stating that religious conflicts in Ethiopia are a result of the intertwined relationship between religion and ethnicity but are not a product of expanding religious extremism.

ACLED recognizes that violence involving religious actors occurs within the larger context of the political and social environment of a country; therefore, no event is purely religious in nature. In this piece, we define religious violence events as incidents that have a clear religious element because of the involvement of religion-based actors, including the targeting of individuals belonging to a specific religious group.

Religious violence in Post-2018 Ethiopia

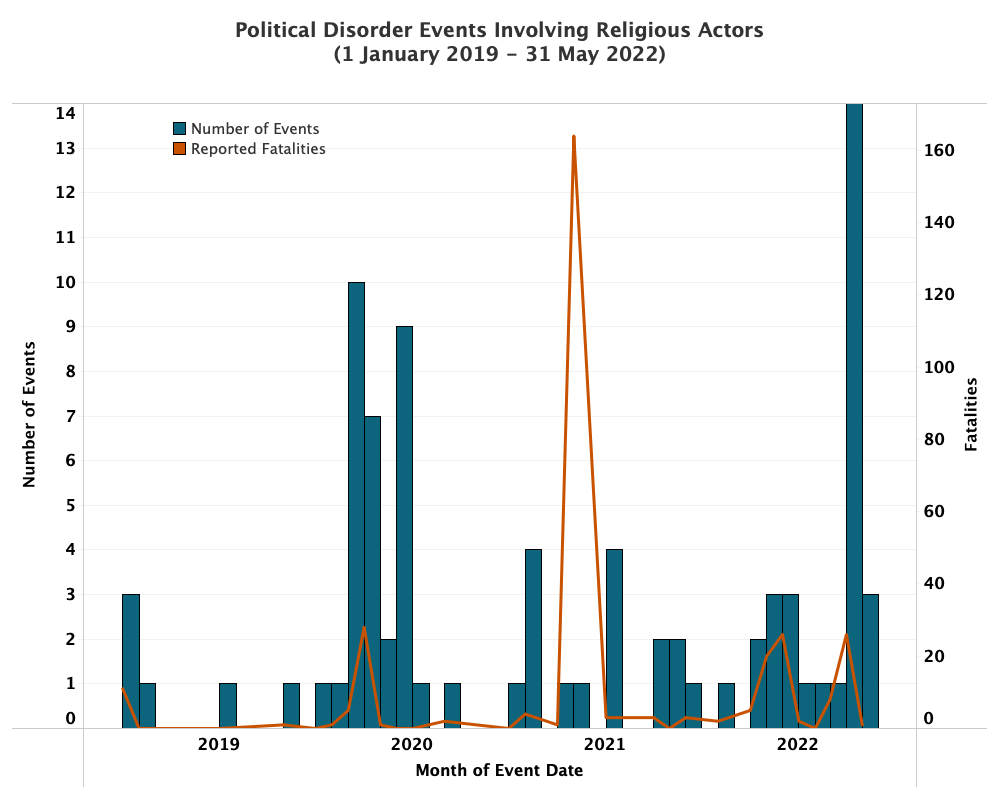

In comparison to pre-2018 Ethiopia, religious strife is becoming more common, and more deadly. ACLED data recorded 14 political disorder events involving religious actors in April, including six political violence events, three violent demonstration events, and five peaceful protests, with 26 reported fatalities.

Religious conflict in Ethiopia has a very different profile than other territory or ethnic-based conflicts in the country, although they are undeniably connected. In contrast to battle events between armed groups – by far the most common type of violence in Ethiopia –, religious conflict in Ethiopia usually occurs in the context of attacks on unarmed civilians, or during riots. Religious groups in Ethiopia are also frequently involved in demonstrations – for example, those held in Addis Ababa by Muslim students rejecting what they deemed “government interference into religious matters” (Addis Standard, 8 April 2022).

Political influence and the use of religion as “a theologically informed political tool” have contributed to heightened tensions between religious actors in Ethiopia (Berkley Center, 19 July 2021). Religious minorities – different groups depending on the location – often face targeted violence because of their association with a particular political group or ethnicity. Supporting this claim, Ethiopian expert Jan Abbink stated: “Only when political interference and political instrumentalization of religion occurs, then you have certain outbursts of violence” (DW, 6 May 2022). Notably, there are clear relationships between religious violence and political violence in Ethiopia. At moments of heightened political tension in the country, religious violence appears to be more likely. Political disorder events in the month of April 2022 showcased an unprecedented wave of religion-related violence this year – mostly in the form of riot events.

Political Fault-Lines Divide Faiths: The Prosperity Gospel

Despite being vastly outsized by Orthodox Christianity and Islam in Ethiopia, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s Pentecostal faith was considered controversial by few at the outset of his tenure in 2018. This is perhaps because his predecessor, Hailemariam Dessalegn, was also a Protestant (Jörg Haustein, December 2013). Abiy’s largest support bases at his appointment were not only in the Protestant strongholds of the west and south of the country but also in Eastern Oromia where Islam is the prevailing religion.

Since Abiy’s dissolving of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) and the establishment of the Prosperity Party (PP), however, Abiy has come under intensified criticism by political opponents, who accuse him of bringing his religion into the country’s politics and filling the government’s top ranks with members of his church (The Economist, 24 November 2018). Abiy’s closest political allies – such as Oromia Regional President Shemelis Abdisa – come from similar religious backgrounds. There are small conflicts that regularly occur over the use of public space that reflect these tensions, especially in urban areas. For example, in April 2022, Orthodox Christians attacked Pentecostal worshippers in the Kora area of Akaki in Finfine special zone in Oromia region after accusing them of noise pollution. One person was killed in the altercation and several injured. In February, a similar incident occurred when Protestant church members attacked Orthodox worshippers in Nekemte town in East Wollega zone in Oromia region, after Orthodox church members tried to block them from cutting down and using trees (ESAT, 10 February 2022). In Gelan town in Akaki woreda, a group of Orthodox believers who claimed to have found a religious artifact in Chefetuma kebele refused to move after local authorities accused them of “land grabbing,” saying the land they had occupied was supposed to be reserved for a government project (BBC Amharic, 8 April 2022). In Addis Ababa, Muslim students held protests against “government interference into religious matters” on 8 April, accusing schools of preventing students from holding prayers and other religious activities on school premises (Addis Standard, 8 April 2022). On 12 April, reports indicating permission for Muslim students to perform noon prayers outside the school were released (BBC Amharic, 12 April 2022).

Many in Ethiopia accuse the Orthodox church – and its historical affiliation with the leaders of Ethiopia – of forcefully dominating public space in Ethiopia. Opponents of the current political administration accuse Abiy Ahmed of the same thing. Yet, trying to pin all of Ethiopia’s religious violence on the religious affiliations of its elite would be vastly oversimplifying a complex set of driving factors, of which religion plays a minor role. More important in examining the causality of religious conflict is to look deeper into the political, and by extension, ethnic associations. As ethno-nationalism in Ethiopia has been on the rise, the religious attachment of many groups to a particular political party has become more extreme. To illustrate this point, it is worth pointing out that recent conflicts in the country led to the split of the major religious organizations, rather than them insulating themselves from the political conflicts in which they had become irreversibly involved. In other words, the conflict drivers pushing violence in contemporary Ethiopia appear to be much stronger than the bonds of common faith. This may also explain the failure of religious leaders to stop or even mitigate conflict that has been raging in the country since November of 2020 (Inter-Religious Council of Ethiopia, 4 November 2020).

In May 2021, the Ethiopian Orthodox church patriarch, an ethnic Tigrayan, spoke out against the conflict in Tigray and labeled the conflict as “genocide” against ethnic Tigrayans (VOA, 9 May 2021). A spike in fatalities in events involving religious actors (see graph below) in November of 2020 can be attributed to violence targeting religious actors and worshippers in Tigray region as part of the northern conflict between the government and TPLF (EHRC, 23 March 2021). The patriarch, however, failed to address the attack against other ethnic groups like ethnic Amharas in Mai Kadra in Western Tigray zone, and Oromia region. Many criticized the patriarch for taking sides, rather than condemning all atrocities and violence against civilians in the country as a religious leader.

Although religious leaders in both Tigray and the rest of the country denounced the conflict when it began, they were ultimately unable to overcome the political differences of the warring factions they associate with. Both the Ethiopian Orthodox church in Tigray and the Tigray Islamic Affairs Council have severed ties with their respective organizations at the federal level (Africa Intelligence, 23 February 2022). Oromo ethno-nationalist actors threatened a similar split in 2019, when political elites from Oromia region backed a move by local church officials to break from the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church over a dispute regarding language services (DW, 4 September 2019).

Religious Violence as an Extension of Political Conflict

Religious minorities in various locations throughout the country have suffered an increasing number of violent attacks against their communities over the past few years. In many cases, minorities are targeted due to their assumed political identities.

On 26 April 2022, an unidentified armed group attacked Muslims in Gondar city after violence erupted during the funeral of a prominent local sheikh. A bomb was thrown into a group of Muslims as they attended the funeral, killing three people and wounding five others. The violence spread into the city when rioters attacked and burned more than 20 Muslim businesses and houses. Rioters also burned mosques and looted 11 residences (Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation, 29 April 2022). This reportedly led to the deaths of 17 people, and an additional 118 people were also injured. The unrest in the city continued for the next few days. On 28 April, three people were killed and an unspecified amount of properties were damaged in Gondar city due to unrest after a funeral ceremony of people who were killed in the attack on 26 April. Police arrested more than 370 people accused of looting properties and destroying religious places and other properties (Amhara Media Corporation, 29 April 2022). Six political and security sector leaders were also arrested later in Gondar for not taking appropriate measures during the 26 April unrest (Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation, 3 May 2022).

Events in Gondar last month and in Oromia in 2019 have many parallels. In October 2019, violent rioters in the eastern parts of Oromia region attacked Orthodox churches – which are associated with the old Ethiopian Empire under which ethnic Oromos were oppressed – killing numerous people over a period of a few days. Hundreds of Orthodox Christians – most of whom are ethnic Amharas – have been killed in rural areas of Oromia region during attacks by communal militias and the OLF-Shane since 2019.

Both the 2019 and 2022 incidents involved minority religious groups that were attacked in the context of heightened political tensions, involving actors linked to growing ethno-nationalist organizations. Both occurred in the context of a changing ‘status quo’ that was perceived as a threat to a community’s identity. In eastern Oromia, an area traditionally dominated by Muslim Oromos, migrant ethnic Amhara workers, shop owners, and companies have led to a rapid growth in the population of Orthodox Christians in the cities and towns throughout eastern Oromia. In Gondar, similar dynamics exist, where a traditionally Orthodox space has taken on a large number of Muslim residents. Unhelpfully, in both cases, the minorities are known to be relatively wealthy as a result of their ability to leverage an economic advantage through links to their home locations. In both cases, attackers were seeking to protect what they viewed as status quo, destroying buildings and attacking minorities after other political conflicts triggered a start of violence (European Institute of Peace, January 2021).

Also in both cases, violence spread quickly to affect urban locations throughout the country. Two days after the initial attack, on 28 April 2022, a group of Orthodox Christians attacked and burned two mosques in Debark town in North Gondar zone in Amhara region. The attack occurred after a rumor that the Gotet Mariam Orthodox Church in kebele 01 burned down when, in fact, a fire occurred inside the compound of the church but the church did not burn down. It is not clear if someone set this fire on purpose, or if it was an accident (EMS, 28 April 2022). According to the head of the North Gondar Zone Security Office, one member of the security forces was killed by an unidentified shooter from a nearby mosque (Debark City Communication, 28 April 2022). A peaceful protest against the attack on Muslims in Gondar was held in the Anwar Mosque in Addis Ababa on 27 April. Two days later, Muslims gathered in Jimma in Oromia region, Dire Dawa, Semera in Afar, Jigjiga in Somali, and Werabe in SNNPR to demonstrate against the attack on Muslims in Gondar city. The demonstration in Dire Dawa city turned violent as demonstrators threw stones at police and injured 22 officers. Demonstrators also damaged banks and government vehicles. In return, police forces opened fire. One child was killed by a stray bullet. Eighty-nine people were arrested in Dire Dawa in connection with this violent demonstration. In Werabe, Muslim demonstrators attacked and burned two Orthodox and three Protestant churches on 28 April. The next day, they burned another Orthodox church. Similarly, on 28 April, a group of Muslim rioters entered the Sankura St. Gebrael Church in Alem Gebeya in Sankura woreda in Silte zone in SNNPR, attacking the monks and burning the church. The rioters also destroyed hotels belonging to Christians, injuring around 15 people. According to the Silte Zone Administration Communication Office, 79 people were arrested in connection with the violent demonstrations in Werabe and Sankura (VOA Amharic, 9 May 2022).

Ethnicity and the Question of Religious Unity

While ethnicity and religion are often linked in the formation of Ethiopian identities, ethnicity can also crosscut traditional religious boundaries, forming minority identities that find their mild political footing hard to define amid a changing environment. By default due to their minority status, these communities often show high support for the federal government and express distaste for ethno-nationalist tendencies. For example, traditionally Muslim areas of eastern Amhara region turned out in heavy support for the Prosperity Party in the latest national elections, but often express discomfort amid the rise of Amhara ethno-nationalism, which leans toward the Christian faith and Orthodox tradition (NEBE, 14 June 2021). Similarly, Orthodox Oromos in areas of Western Oromia, or Christian Oromos in general throughout eastern Oromia, may support the federal government out of fear that Oromo ethno-nationalist agendas as defined in their locations might not include them given their status as a religious minority.

As a final point, the most serious, fatal, and damaging violence that has involved religious sites and actors in Ethiopia has occurred in the context of the ongoing northern conflict. As a result of the conflict, the religious communities of Tigray, Amhara, and Afar regions have undergone irreparable damage, and lives and historical heritage artifacts have been lost. In late November of 2020, the ancient Al Nejashi Mosque – erected in the seventh century and featuring the tombs of the first Muslim immigrants in Ethiopia – was hit by shelling and destroyed (AFP, 29 April 2021). Dozens of other religious sites were also deliberately damaged during the conflict (The Jerusalem Post, 30 March 2022).

Religious conflicts in Ethiopia are deeply connected with the ongoing political turmoil that is affecting Ethiopia today. Ethiopian religious leaders that have traditionally played key roles in mitigating conflict have been unable to stop any of the various conflicts raging throughout the country. However, as highly influential individuals, their future contributions to conflict mitigation should not be undervalued.