February at a Glance

VITAL TRENDS

- ACLED records 41 political violence events and 268 reported fatalities in February. The number of all recorded event types decreased from January, except for protests.

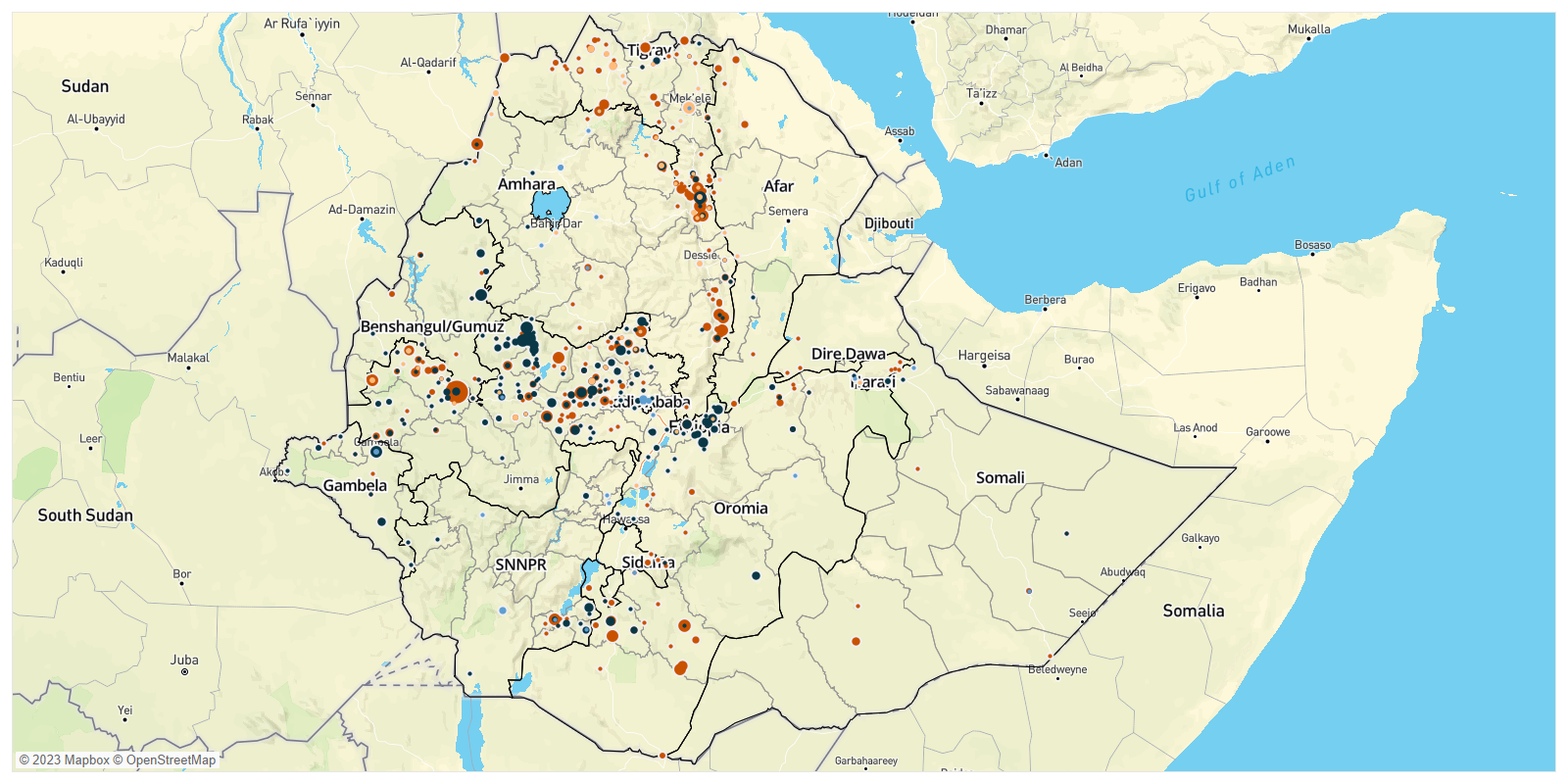

- In February, Oromia region had the highest number of recorded political violence events, at 31, followed by Amhara and Gambela regions, with three events each. Since January 2022, Oromia has had the highest number of recorded political violence events in Ethiopia.

- In February, the most common event types were violence against civilians, with 22 events, and battles, with 17 events. The number of battle events decreased by 74% compared to January. Most of the violence against civilian events were perpetrated by Oromia regional special forces and recorded in Oromia region.

KEY EVENTS IN FEBRUARY

Monthly Focus: Religious Disputes and Government Involvement in Ethiopia

Instability due to religious disputes has been increasing in Ethiopia. In February, ACLED records 13 disorder events involving religious actors. The majority of Ethiopians are Orthodox Christians, followed by Muslims. Recent violence in connection with these religions shows how the involvement of the government in religious matters can fuel religion-related disputes rather than resolve them. This report examines the main causes of these disputes, including government involvement in religious issues, and potential risks for escalation.

Last month, religious tensions in the country were high following an internal dispute within the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church (EOTC). The dispute began on 22 January, when Archbishop Abune Sawiros, along with two other archbishops, appointed 26 bishops in Haro Beale Wold Church in Woliso town in South West Shewa zone, Oromia region, and announced the establishment of the ‘Holy Synod of Oromia and Nations and Nationalities,’ without approval from the EOTC synod.1Oromia Broadcasting Service TV, ‘The Tewahedo Orthodox Church leadership issues a statement,’ 22 January 2023 The new group stated that these appointments were necessary to resolve the long-lasting shortcomings of the church in serving believers in their native languages. The new synod also accused the EOTC synod of appointing its leadership from mostly “one group” and failing to be all-inclusive.2OBS TV, ‘The Tewahedo Orthodox Church leadership issues a statement,’ 22 January 2023 The EOTC synod, meanwhile, accused the new synod of not following the church’s dogma, labeled the Holy Synod of Oromia and Nations and Nationalities “illegal,” and excommunicated the three archbishops and 25 of the appointed bishops.3Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahdo Church TV, ‘The decision of the Holy Synod,’ 26 January 2023. One of the bishops left the group led by Abune Sawiros and joined the Ethiopian Orthodox synod after submitting an apology to the patriarch of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. See EOTC TV, ‘Abba Tsegazeab Adugna asked for forgiveness,’ 25 January 2023 The EOTC synod also outlawed negotiations with the group led by Abune Sawiros on the grounds of it “indirectly breaking the dogma of our church.”4EOTC TV, ‘The decision of the Holy Synod,’ 26 January 2023

Tensions further increased in the country as the government became involved. The situation turned violent when regional security forces began arresting archbishops, bishops, and believers who refused to hand over control of Orthodox churches in Oromia to the newly established Holy Synod of Oromia and Nations and Nationalities. At least eight people were reportedly killed, and many were injured, as factions from the different synods clashed over control of churches in the region (for more details, see EPO Weekly: 28 January-3 February 2023; EPO Weekly: 4-10 February 2023; EPO Weekly: 11-17 February 2023).

Ethiopia’s constitution provides for the separation of state and religion, with the government not permitted to interfere in religious matters or religious authorities in political affairs.5Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Article 11, 1995 Notwithstanding, various governments in Ethiopia’s history have interfered in the internal affairs of the EOTC as well as those of the Ethiopian Islamic Affairs Supreme Council. The violent involvement of Oromia regional security forces in the recent internal dispute of the Orthodox Church by siding with the Holy Synod of Oromia and Nations and Nationalities risks widening ethno-political tensions throughout the country. As ethno-nationalism in Ethiopia has risen, the religious attachment of many groups to particular political parties has become more intense. This is particularly salient among ethnic Amharas, with rising Amhara nationalism emphasizing Ethiopia’s connection to its Christian empire heritage through the EOTC.6Andrew DeCort, ‘Christian Nationalism Is Tearing Ethiopia Apart,’ Foreign Policy, 18 June 2022 To illustrate this point, it is worth pointing out that recent conflicts have led to fractures in religious organizations, rather than the organizations being able to withstand political stresses internally (for more information, see EPO Monthly: April-May 2022). These dynamics also place the federal government in a difficult position, as regional authorities act in contradiction to the “importance of respecting rules and regulations,” which was promised by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed in 2018.7Fana Television, ‘Prime Minister Dr. Abiy Ahmed’s full speech in Parliament,’ 3 April 2018

In relation to the EOTC internal dispute, Prime Minister Abiy encouraged the factions to resolve their differences through dialogue and said, “the government cannot ignore the [people’s] request of being served in their native language.”8Facebook @Abiy Ahmed Ali, 31 January 2023 He reaffirmed that the government would not interfere in internal disputes and asked his cabinet not to get involved.9Facebook @Abiy Ahmed Ali, 31 January 2023 The Federal High Court of Ethiopia later issued an injunction order in favor of the EOTC, prohibiting members of the Holy Synod of Oromia and Nations and Nationalities from entering any EOTC parish or church.10Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church Broadcasting Service Agency, 10 February 2023

Tensions over the language of church services or government intervention in church affairs are not new for the EOTC. In 2019, a similar movement to establish an ‘Oromia Orthodox Church’ was launched by a Kesis (priest), Belay Mekonen, who wanted to see Orthodox church services conducted in Afaan Oromo (Oromo language).11Borkena, ‘Radical ethnic nationalists move to break up Ethiopian Church in pursuit of forming Oromia Orthodox Church, Ethiopian Church Holy Synod responds to it,’ 31 August 2019 The dispute between Kesis Belay Mekonen and the EOTC was resolved through reconciliation in 2020, although some unresolved issues resurfaced with Abune Sawiros last month.12BBC Amharic, ‘”In reconciliation, everyone is a winner” – Kesis Belay,’ 24 October 2020 During the war in Tigray, the archbishop of Tigray declared the separation of the Tigray Orthodox Church from the EOTC synod.13Desta Heliso, ‘The Crisis of Schism in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church,’ Religion Unplugged, 4 February 2023 Recently, the Council of Bishops of the Tigray Orthodox Church rejected an invitation from the EOTC synod requesting talks of “reconciliation and normalization of relations,” accusing the EOTC of supporting a “war of genocide.”14Medihane Ekubamichael, ‘Analysis: Tigray Orthodox Church declines call by Synod to normalize relations, blames Synod for endorsing “war of genocide” on people of Tigray. What next?,’ Addis Standard, 21 February 2023 During the conflict, the EOTC did not release an official statement. However, in May 2021, the EOTC synod patriarch, Abune Mathias, who is ethnic Tigrayan, labeled the conflict as “genocide” against ethnic Tigrayans.15Reuters, ‘Ethiopian Orthodox Church head says genocide is taking place in Tigray,’ 9 May 2021; Voice of America, ‘Ethiopian Orthodox Church Patriarch Blasts Tigray ‘Genocide,’’ 9 May 2021 Many people criticized the religious leader for taking sides, rather than condemning all atrocities and violence against civilians in the country.

The dispute between the EOTC and the Holy Synod of Oromia and Nations and Nationalities subsided after the two sides consulted with Prime Minister Abiy and elders, reaching an agreement consisting of 10 terms.16Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation, ‘A discussion program prepared to resolve the disagreement between the fathers of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church Etv | Ethiopia | News,’ 16 February 2023; EBC, ‘A discussion program prepared to resolve the disagreement between the fathers of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church Part-2 Etv | Ethiopia | News,’ 17 February 2023 The terms included strengthening the church’s services in Afaan Oromo and reinstating the status of the three archbishops and 25 bishops who had been excommunicated by the EOTC.17EOTC Broadcasting Service Agency, ‘Agreement between holy synod and fathers who performed the illegal sacrament,’ 15 February 2023 However, some of the appointed bishops have reportedly been continuing to take control of EOTC churches in Oromia with the support of security forces.18See EOTC Broadcasting Service Agency, ‘It has been announced that a person who claims to be the manager of the Diocese of Shashemene Debre Sebhat Saint Michael Church has arrived,’ 6 March 2023; EOTC Broadcasting Service Agency, ‘The Holy Synod held a discussion with His Holiness Abune Sawiros and His Holiness Abune Eostatheos,’ 28 February 2023 Nevertheless, as of 24 February, people arrested in connection with the crisis are still in prison, including members of the church leadership.19Esubalew Gashaw, ‘The holy fathers are going to visit youths arrested in Awash Sebat,’ Addis Maleda, 24 February 2023

Ethiopia’s Islamic community also experienced some unrest over its leadership in February. Near the end of the month, internal disputes related to the appointment of the Ethiopian Islamic Affairs Supreme Council (commonly known as the Mejlis) threatened to divide Muslims in the country. On 19 February, a group of worshippers blocked members of the newly appointed Mejlis from making a speech in the Fetih Mosque in Nekemte, Oromia, beating and injuring worshippers and smashing windows. Earlier, on 10 February, seven Muslim elders and religious teachers were arrested after the new Mejlis had asked them to relinquish the biggest mosque in town. Suffi Muslims in Nekemte blamed the new Mejlis, which they claim to be “dominated by the Wahhabi sect,” for inciting violence.20Addis Maleda, ‘What happened to the Muslims of Nekemte? Arrest of the youths who protested the demolition of houses in Sululta, the high representative of America in Addis Ababa!,’ 15 February 2023 Similar issues also reportedly arose in Addis Ababa, Harar, Ilu Aba Bora, Jimma, and Adama.21Addis Maleda, ‘What happened to the Muslims of Nekemte? Arrest of the youths who protested the demolition of houses in Sululta, the high representative of America in Addis Ababa!,’ 15 February 2023 Furthermore, Muslims in Kombolcha peacefully protested in South Wello zone, Amhara region, condemning the “illegal takeover of Mejlis by the Wahhabi sect.” The protesters chanted slogans including “our leader is Haji Omer Idris,” “Islam is not for sale,” and “Mejlis belongs to Muslims, not to Wahhabis.”22Addis Maleda, ‘It was said that an unknown number of people were injured due to a problem that occurred in a mosque of Nekemte city,’ 21 February 2023

The dispute in connection with the Mejlis began in 2012, when the government began to enforce al-Ahbash (the Ethiopian) – also known as the Association of Islamic Charitable Projects – teaching in the country following the March 2011 religious violence in Asendabo and Omo Nada areas near Jimma town.23Addis Standard, ‘Religious tension in Ethiopia,’ 27 March 2013; U.S. Department of State, ‘Country Reports on Terrorism 2011, Chapter 2. Country Reports: Africa Overview,’ 31 July 2012; William Davison, ‘Muslims accuse Ethiopian government of meddling in mosques,’ The Christian Science Monitor, 31 May 2012 Founded in the 1980s by Sheikh Abdullah al-Harrari, al-Ahbash teaching opposes ultra-conservative ideology. Its beliefs are derived from an interpretation of Islam combining Sunni Islam and Sufi elements. The government has encouraged this teaching as a means to counter violent extremism. Historically, Ethiopian Muslims practiced Sufism, but influence from the Gulf region has led to the wider adoption of Salafism since the 1990s.24Terje Østebø, ‘Local Reformers and the Search For Chance: The Emergence of Salafism in Bale, Ethiopia,’ Africa, 13 October 2011

In 2012, mass demonstrations were held by Ethiopia’s Muslim communities in response to changes in the curriculum and the firing of 50 teachers from the Awolia religious school in December 2011.25The New Humanitarian, ‘Ethiopia’s Muslim protests,’ 15 November 2012; France24, ‘Ethiopia’s Muslims protest against being “treated as terrorist,”’ 25 July 2012 Demonstrators accused the government of dictating the election of the Mejlis’s leaders in order to establish an al-Ahbash-dominated Mejlis.26Aaron Maasho, ‘Ethiopia mosque sit-ins see deaths, arrests: protesters,’ Reuters, 15 July 2012; France24, ‘Ethiopia’s Muslims protest against being “treated as terrorist,”’ 25 May 2012 To represent Muslim interests and discuss the matter with the government, the Muslim Arbitration Committee consisting of 17 prominent leaders was established in 2012. However, the government arrested protest leaders who were held in prison for an extended period,27Human Rights Watch, ‘Ethiopia: Prominent Muslims Detained in Crackdown,’ 15 August 2012; Committee to Protect Journalists, ‘Ethiopian authorities crack down on Muslim press,’ 10 August 2012 while nationwide demonstrations continued under the slogan “Dimtsachin Yisema” (hear our voices).28Borkena, ‘Ethiopian Muslims Marched in support of incarcerated Committee Members,’ 30 May 2014; Philipp Sandner, ‘Muslims protests in Ethiopia,’ Deutsche Welle, 9 August 2013 In November 2012, a new Mejlis with a majority of al-Ahbash adherents was established.29The New Humanitarian, ‘Ethiopia’s Muslim protests,’ 15 November 2012; Voice of America, ‘Ethiopia Presents New Islamic Council,’ 5 November 2012 Years later, when Prime Minister Abiy came to power, he released prominent Muslim leaders and activists. In 2019, he established a committee comprising nine religious figures from the 2012 Muslim Arbitration Committee, the Mejlis, elders, and religious scholars, with the aim of reforming the Mejlis.30Borkena, ‘Abiy Ahmed got rival groups within Ethiopian Muslim community talking,’ 4 July 2018

On 18 July 2022, a new Mejlis was established led by Haji Ibrahim Tufa – reportedly a Wahhabi. Although the government promoted this Mejlis as representing the will of the entire Muslim community, some Muslims did not accept it and accused the government of interfering. Hence, when members of this Mejlis tried to implement the new structure and take over mosques, they were met with riots and demonstrations by Sufi Muslims in Nekemte in East Wollega zone, Oromia, and in Kombolcha in South Wello zone, Amhara (for more, see EPO Weekly: 18-24 February 2023).

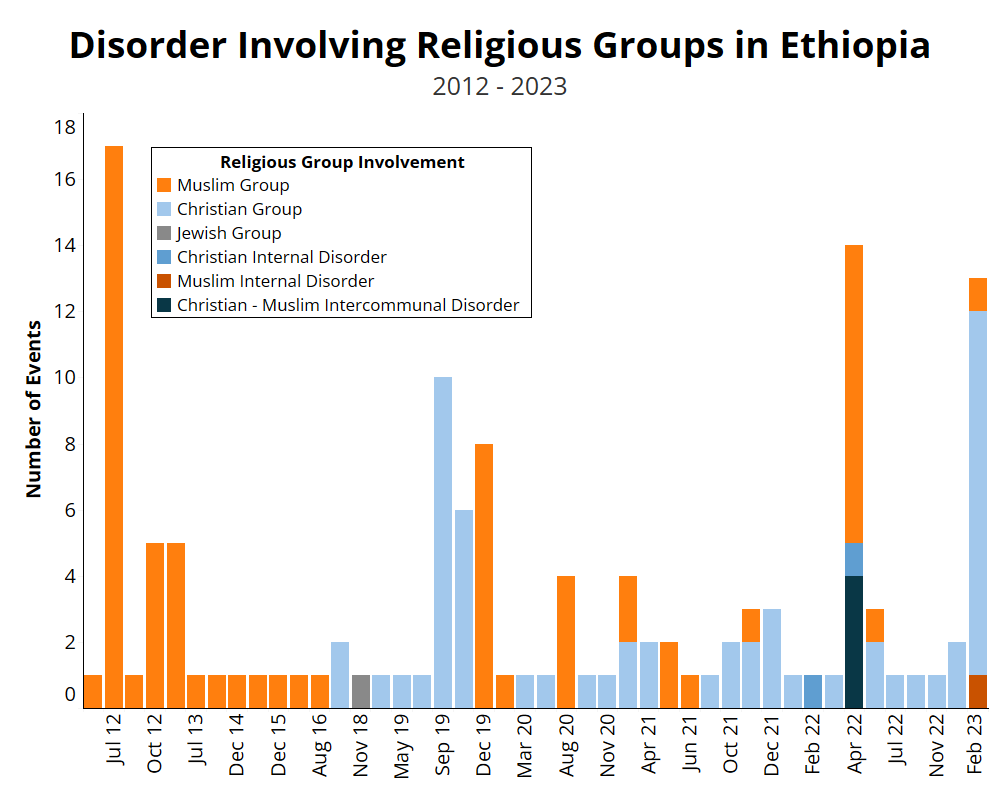

The lack of separation between state and religion is becoming another cause of violence in the country. Both the EOTC and some Muslims accuse the government of interfering in their internal affairs. The frequency of religious-based violence is increasing. In 2022, ACLED records 25 disorder events involving religious actors, with the majority of these events – 86% – occurring in connection with the Gondar incident in April (for more, see EPO Weekly: 23 April-6 May 2022). This represents an increase of 39% in total events recorded annually compared to 2021, which records 18 disorder events involving religious actors. Before this, the last years which recorded high numbers of disorder events involving religious actors were 2012 and 2019 (see graph below). In 2012, all religious disorder events involved Muslim groups, related to the reasons outlined above. The religious disorder events in 2019 involved the targeting of Orthodox churches in Oromia following the arrest of a popular social media activist and the subsequent targeting of mosques in Amhara region in retaliation. In 2023, for February alone, ACLED records 13 disorder events involving religious actors.

Ethiopia’s population is deeply religious, with fractures in the EOTC and Muslim communities sensitive issues that affect many of the country’s inhabitants. During the recent EOTC dispute and violence, many Orthodox Tewahedo believers announced their readiness to die ‘as a saint’ protecting the church.31EOTC Broadcasting Service Agency, ‘Orthodoxes are showing their stand,’ 4 February 2023; see also the comments under this post: EOTC Broadcasting Service Agency, ‘“The martyrs truly despised the taste of this world; They shed their blood for God. Endure a bitter death for the sake of heaven,”’ 6 February 2023 Supporters of the breakoff faction of the church have likewise expressed a deep commitment to Abune Sawiros.32Addis Standard, ‘News: Dissenting Archbishop returns to Diocese where Church schism first ruptured as Holy Synod continues rejection,’ 9 February 2023 Compared to pre-2018 Ethiopia, religious strife is becoming more common and deadly. Political influence and the use of religion as a political tool have contributed to heightened tensions between religious actors in Ethiopia.33Mohammed Girma, ‘Religion and the Social Covenant in Ethiopia: Faith in the Tigray Conflict,’ Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs, 19 July 2021 According to Ethiopian expert Jan Abbink, “only when political interference and political instrumentalization of religion occurs, then you have certain outbursts of violence.”34Alemnew Mekonnen and Benita van Eyssen, ‘Interfaith tensions simmer in Ethiopia,’ Deutsche Welle, 6 May 2022 In Ethiopia’s increasingly polarized political landscape, where factions are instrumentalizing religious institutions, further violence involving religious actors is likely to occur.