A year after SNNPR’s dissolution, violence returns to historically troubled areas

September 2024

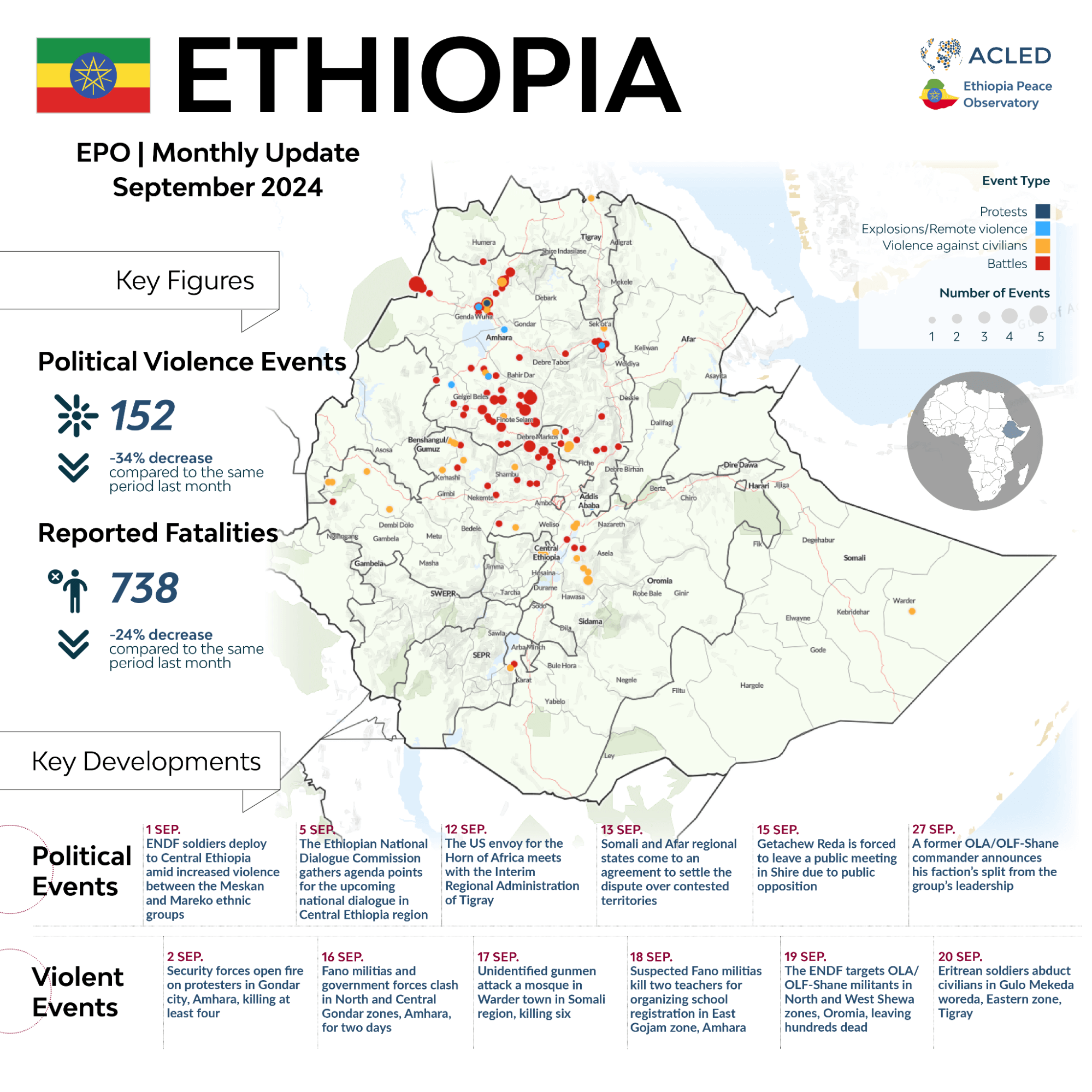

September at a glance

Vital Trends

- In September, ACLED records 152 political violence events and 738 reported fatalities in Ethiopia.

- Battles and violence against civilians were the two most common events in September, with 107 and 38 incidents, respectively. Most of these events were linked with the ongoing conflict between government and insurgent forces in the Amhara and Oromia regions.

- In September, ACLED records the most political violence — 102 events and 318 reported fatalities — in Amhara region, followed by Oromia region, with 43 events and 398 reported fatalities.

A year after SNNPR’s dissolution, violence returns to historically troubled areas

On 19 August 2023, two new regions – South Ethiopia and Central Ethiopia – were established, effectively dissolving the former Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s region (SNNPR). Now, just over one year after the dissolution of the SNNPR, violence has returned to areas that experienced high levels of violence prior to the dissolution of the region, with implications reaching beyond the geographically small areas affected. With the new cluster systems cutting the former SNNPR into smaller, more manageable regions, violence was expected to decrease, and conflicts associated with autonomy requests and intercommunal issues were expected to improve. Instead, in some areas of the former SNNPR, violence has continued.

The former SNNPR region provides a case study on the relationship between violence and Ethiopia’s ethno-federalist government. In some ways, it is a microcosm of the rest of the country, including its power struggles and political issues over territory linked to an ethnic group.

The dissolution of SNNPR

SNNPR was the most diverse region in the country, containing dozens of ethnic and language groups. Management of such a diverse set of actors in an ethno-federal system was a major challenge for even some of Ethiopia’s more seasoned politicians.1Arefaynie Fantahun, ‘Shiferaw Shigute, Head of EPRDF’s Southern Party, Resigns After Ethnic Violence,’ Ethiopian Observer, 25 June 2018 Two major conflicts that existed in the former SNNPR, the Mesken/Mareko conflict and the Konso/Segen conflict, are good examples of how political boundaries linked to ethnicity can foster violent competition between ethnic groups. In both cases, local elites have sought to control greater territory and resources and do so by organizing ethnic-based militias that then engage in conflict. In the Konso/Segen conflict, elites who used to control greater territory lost it when Konso gained zone status in 2018. These groups oppose Konso zone’s independence and wish for a larger Gumayde Peoples Special woreda structure.2Addis Standard, ‘News Analysis: Konso zone and Segen Woreda admins, security officials discuss ways to jointly tackle ongoing security crisis in Segen,’ 25 April 2022 In the case of the Mesken/Mareko conflict, violence has been the result of an unsettled dispute between Meskan and Mareko ethnic groups over the ownership — and political ‘right’ to govern — of nine kebeles within the Guraghe zone.

The creation of the new regions in the former SNNPR marked a novel moment in Ethiopia’s history. Demands for the autonomy to which all of Ethiopia’s ethnic groups are constitutionally entitled — long repressed under the former government — were being partially granted under a proposed solution of ‘clustering’ of ethnic groups into four smaller regions. With this clustering, ethnic groups in the former SNNPR were divided into smaller regions, also theoretically allowing for more representation by any given ethnic group as they existed within a smaller political unit compared to the former SNNPR region. The government advocated for the cluster solution as a step toward a more peaceful and prosperous Ethiopia, citing reduced geographic distance between the regional government offices and its people. Further, it argues that within the smaller region ‘clusters’ the elites of the new states now have greater access to civil service jobs, political positions, regional budgets, and federal subsidies.3Chalachew Tadesse, ‘Referendum in Ethiopia’s Southern Region,’ Rift Valley Institute, March 2023 Opponents to the cluster system expressed worried that allowing some demands and repressing others could open a Pandora’s box of autonomy demands and spiral out of the newly formed regional governments’ control. In practice, the cluster solution was a top-down approach, as the new regions contain several zones and special woredas grouping ethnic groups together (as the federal government wished), rather than allowing each ethnic group true autonomous governance as the constitution allows.

The former SNNPR: One year in

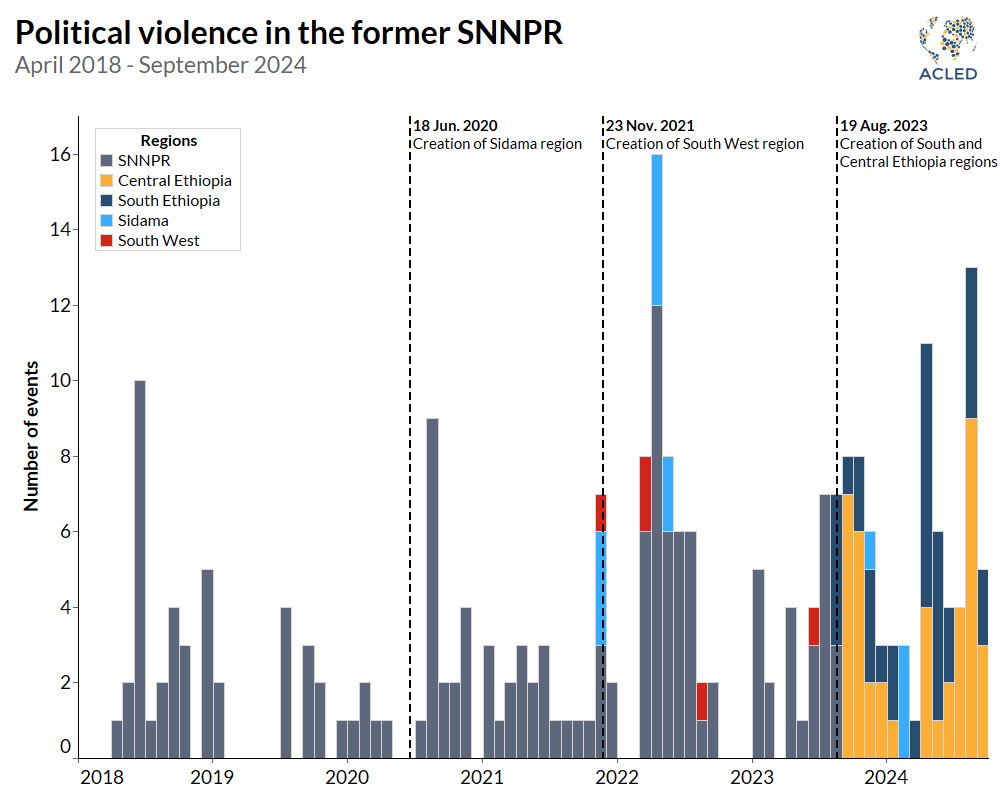

September 2024 marks a year and one month since the SNNPR region was dissolved and the cluster system implemented. Violence patterns in the former SNNPR indicate that the creation of the new regions initially reduced violence, which reached a low point between January and March 2024. However, it has failed to eliminate violence, as ethnic-based clashes returned in Central and South Ethiopia regions beginning in April (see graph below).

A closer look at the conflicts in the former SNNPR region reveals that conflicts have evolved very little as a result of the new regions. Between April 2018 and August 2023, most political violence in SNNPR was recorded in Sidama, Konso, and Gurage zones. This violence was related to requests for autonomy and administrative boundaries. After the dissolution of SNNPR, similar violence has been recorded in the Gurage zone — now divided into three administrative levels4East Gurage woreda has been designated as a separate zone, and Kebena and Mareko woredas have been designated as special woredas. — and around Konso. Clashes and targeted violence between the Mesken and Mareko ethnic groups have contributed the most incidents in Central Ethiopia region, while violence in the Konso and Segen Area Peoples zones has contributed most incidents to the totals in South Ethiopia region. Both conflicts existed prior to the creation of the new regions, with violent incidents recorded in August and September. The Mesken and Mareko conflict in Central Ethiopia region reached such a point that the federal forces were deployed at the beginning of September. In Segen town of South Ethiopia region, at the end of August, Derashe ethnic militias took control of the town for several days, leaving only as the federal forces arrived to regain control. The federal military has been actively involved in SNNPR throughout the years, including in April 2022 in Derashe special woreda following widespread unrest in areas near Segen town.

On the one hand, it could be argued that the new system has not had the time to run its full course: New officials have yet to settle into office, and political systems are young. On the other hand, violence levels that dropped at the creation of the new regions have risen over the past few months, drawing a worrying trend. Increasingly frequent attacks against civilians in the Mesken/Mareko area and a resurgence of violence in the Konso/Segen area indicate that violence is likely to continue unless a more permanent solution is found.

In many cases, the new regional governments have struggled in aspects beyond just security, especially in relation to the delivery of public services. Staff in major hospitals in Shone, Hadiya zone, in Central Ethiopia region went on strike over a lack of salary payments in July 2024.5Shawangazew Wagehu, ‘Salary strike in Hadiya zone,’ DW Amharic, 22 July 2024; VOA Amharic, ‘Residents have expressed their distress because the unpaid hospital workers stopped working in Hadiya,’ 23 October 2023 The Sidama region also faced the same issue.6Mistir Sew, ‘Central state’s fiscal control stunts Ethiopian federalism,’ Ethiopia Insight, 21 April 2023 This trend, like violence patterns, is not necessarily unique to the newly created regions but rather a holdover from the previous SNNPR administration for these areas that were not solved by the creation of the new regions. ACLED records at least four other protests between April and August 2023, with demonstrators similarly demanding that unpaid salaries be settled. Authorities responded with arrests and forcefully dispersed protesters.

Moving forward: The future of the south and its implication for the rest of Ethiopia

Additional re-organizations of zones or new regions are unlikely in the new southern regions. Outside of appointment and reorganization, federal authorities appear to have closed their position on autonomy requests. For example, in the case of Gurage zone, federal authorities warned that they “will not tolerate illegal and irregular activities under the guise of the restructuring requests”7Addis Standard, ‘News: SNNP Council submits zonal, special woredas restructuring to House of Federation; Bu’i city in Gurage zone establishes command post,’ 5 August 2022 and arrested people accused of supporting the self-administration request of Gurage zone. Some elites have been demanding a regional status for Gurage zone, like Sidama region, for years. Similar crackdowns have occurred in the context of demands by the Zeyise ethnic group to be recognized as a special woreda and gain special governance status in areas near Arba Minch.

Violence in the former SNNPR is likely to continue to escalate as groups explore options for pressuring new authorities, especially in areas where groups were not granted requested autonomy as allowed under the constitution. In other areas, like Sidama region, violence is not likely to return except in border disputes with neighboring ethnic groups. Thus far, since SNNPR was dissolved in August 2023, an estimated 850,800 people have been exposed to political violence. This is low compared to the rest of Ethiopia, as conflicts tend to be extremely localized. However, as occurred in the Konso zone in April 2022, even localized conflicts can overwhelm local authorities and result in thousands of displacements. Traditional reconciliation meetings held in February 2024 in relation to the Mesken/Mareko clashes do not appear to have had an effect.8Ethiopian Human Rights Commission, ‘The situation of human rights in conflict areas in Ethiopia,’ 28 September 2024 Unfortunately, as long as ethnic federalism is the main basis for governance in Ethiopia, areas of the country’s former SNNPR that contain ethnically diverse populations will face difficulties in managing political expectations for autonomy.

The experience of the newly formed regions of the former SNNPR forms an interesting example of what could happen in Ethiopia’s future, specifically if the larger regions in the country were reduced to smaller cluster regions to allow for autonomy requests from sub-groups contained within the cluster regions. Many sub-clans within the larger ethnic groups exist, as do ethnic minorities within the larger regions. Yet, creating new zones and allowing for additional autonomy requests, while legal under Ethiopia’s current constitution, seems out of the question. Already, a decision made by the Oromia region government to establish a new zone and restructure the administration of several cities was met by resistance and fatal riots in February 2023. Issues dealing with the administration of the contested territory in South Tigray zone resulted in major clashes in February 2024. As evidenced by the examples in the former SNNPR, simply creating additional or smaller political administrative units did not necessarily solve any of the ongoing issues. Any efforts to restructure the current administrative boundaries would likely be met with resistance and struggle.