June – July at a Glance

Vital Stats1ACLED’s real-time data updates are paused through the end of August 2021. Data for the period of 31 July to 3 September will be released on 6 September. All ACLED data are available for download via the data export tool and curated data files.

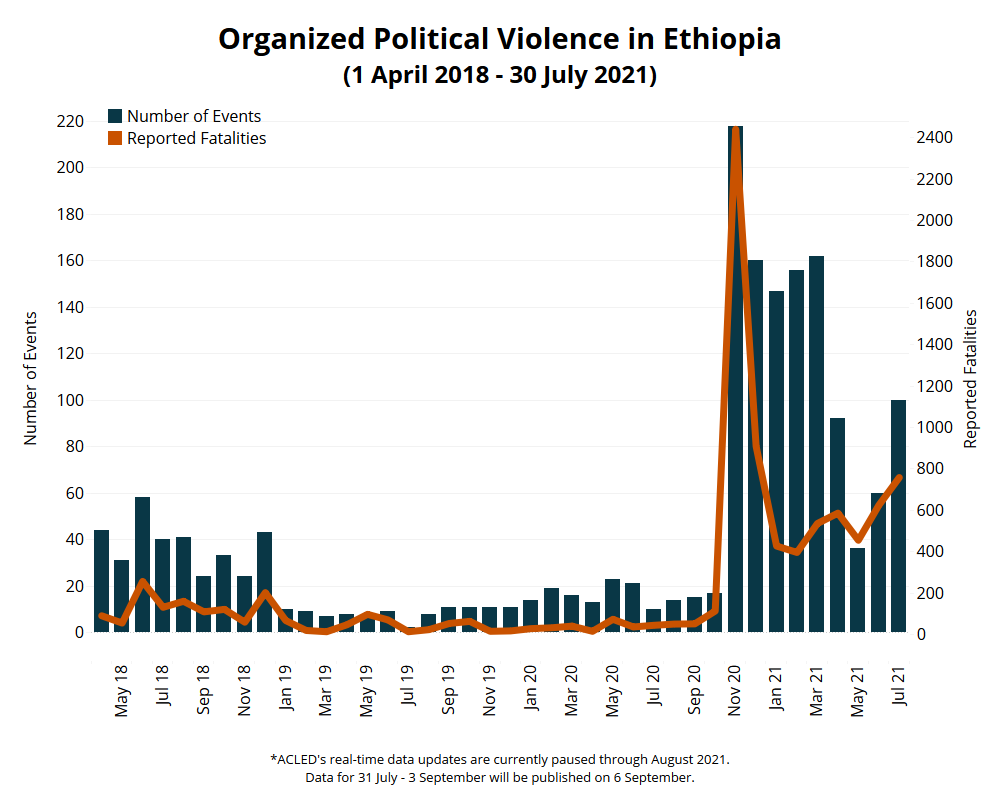

- ACLED has recorded 60 organized political violence events and 624 reported fatalities in June; ACLED has recorded 100 organized political violence events and 758 fatalities in July.

- Afar region had the highest number of reported fatalities due to organized political violence in July at 500 reported fatalities. Tigray region had the highest number of reported fatalities due to organized political violence in June at 423 reported fatalities.

- In June and July, the most common event type was battles, with 105 events and 760 fatalities reported across two months. 64 fatalities were reported in a single airstrike event in Tigray.

Vital Trends

- Some election-related violence, although minimal, was reported in Amhara and Oromia regions in June.

- Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) forces battled government troops and took control of wide swaths of territory, including in Amhara and Afar regions, by the end of July.

- In the Oromia region, clashes between the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF)-Shane and federal and regional security forces were reported during the Ethiopian national election; small skirmishes were reported throughout July.

- In July, tensions between the Somali and Afar region reignited after Afar ethnic militias and militants associated with the Afar Revolutionary Democratic Unity Front (Uguguma) attacked ethnic Somali residents of Gadamaitu town in Gabi-Zone 3 of Afar region.

In This Report

- June-July Situation Summary

- Analysis of TPLF and OLF-Shane insurgencies in Ethiopia

June – July Situation Summary

During the month of June, Ethiopia’s long-awaited election was held in most regions of the country. Despite the expectation by many that the voting would be accompanied by widespread violence, election day passed peacefully in urban areas of the country with some scattered violence in select rural towns.

Still, the TPLF and OLF-Shane insurgencies continued throughout June and into July. OLF-Shane forces fought with Oromia regional special forces in Guji and Borena zones of the Oromia region. They were also active across Horo Guduru Wollega and West Wollega zones. TPLF insurgents swept across the Tigray region in June, fighting battles with Eritrean and Ethiopian forces, and taking control of territory, including the capital of Tigray, Mekele. Ethiopian government troops subsequently withdrew from areas of eastern and southern Tigray during the last days of June.

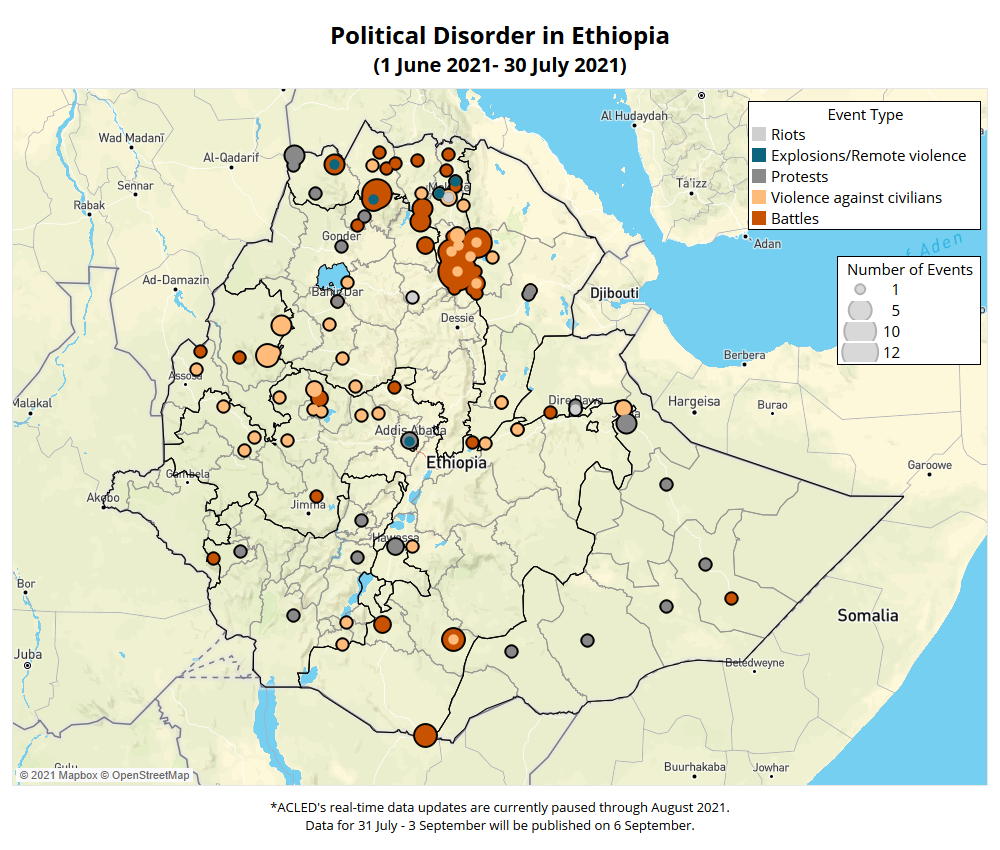

Battles were the dominant form of political disorder recorded in both June and July. Clashes were reported across Tigray, Amhara, and Afar regions (see map below). In June, armed clashes were reported between TPLF and the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) within the Tigray region. The federal government announced a unilateral ceasefire at the end of June. However, in July, armed clashes spread into both Amhara and Afar regions. TPLF forces clashed with the ENDF, as well as Amhara regional special forces and militias and Afar regional special forces and militias, as they attempted to seize areas controlled by the Amhara and Afar regional governments. The TPLF provided two reasons to justify the attacks on neighboring regions: securing humanitarian access and forcing the federal government to accept a list of preconditions for a mutual ceasefire. In July, TPLF released two lists of preconditions for a mutual ceasefire negotiation. The latest list of preconditions was released on 29 July 2021. TPLF officials have indicated that if this list of preconditions is not accepted, its forces will continue to fight with federal forces (Reuters, 6 July 2021; DW Amharic, 5 July 2021).

Many civilians continue to be affected by the ongoing conflict between the TPLF and the federal government. It is estimated that, in July, 150,000 ethnic Amhara people have been internally displaced from the Raya Kobo area and 18,000 from Abergele, Wag Hamra zone. More than 70,000 ethnic Afar from Abala, Dalol, Golba, Erebti, Megale, and Afedere areas of the Afar region are thought to be displaced (ESAT, 3 August 2021).

Other conflicts throughout the country have also impacted civilians. In July, 25 events of violence against civilians were recorded in Ethiopia with a total of 420 fatalities. 300 of these 420 fatalities were recorded in Gadamaitu town in Gabi-Zone 3 of Afar region, making Afar region the region with the highest number of fatalities stemming from violence against civilians in July. These fatalities were reported when Afar ethnic militias and militants associated with the Afar Revolutionary Democratic Unity Front (Uguguma) attacked ethnic Somali residents of Gadamaitu town. This attack in Gadamaitu sparked demonstrations in Dire Dawa and the Somali region.

In Benshangul/Gumuz, violence against civilians increased after a few months of stability. In June, only one fatality was reported due to violence against civilians. In July, 32 fatalities were recorded. Members of the Gumuz armed group shot and killed at least three people in Gilgel Belles in Pawe woreda and one person in an area known as Mangi Ber in Bulen woreda of Metekel zone. As well, unidentified armed men shot and killed 15 people in Bulen woreda in one event and eight people in Denbe Kebele of Metekel zone. Three people in Oda Belgudul woreda in the Assosa zone were also killed by unidentified assailants. Fatalities were also recorded due to a battle. In July, 100 fatalities were recorded due to a single armed clash between ENDF and the Gumuz People Democratic Movement.

Meanwhile, in July, reports indicated that members of Al Shabaab clashed with the Somali region special forces in the Shebele zone in the Somali region, leading to the deaths of an unspecified number of people. Clashes involving Al Shabaab are not common in the Somali region of Ethiopia.

Examining the TPLF and OLF-Shane Insurgencies

On 6 May 2021, the House of Peoples’ Representatives unanimously approved a recommendation by the Council of Ministers to designate two insurgent groups — TPLF and OLF-Shane — as ‘terrorist’ organizations (House of Peoples Representatives of FDRE, 6 May 2021). Both groups are actively fighting with the federal government and have shown signs of increased activity in recent months. As ethnically based organizations that claim to fight for greater political autonomy for their respective ethnic homelands, the TPLF and the OLF-Shane have strong local support within their areas of operation. At the same time, both groups have been accused of the killing and displacement of ethnic minorities in areas under their influence.

As with many other conflicts within Ethiopia, information about the TPLF and the OLF-Shane is convoluted and subject to heavy reporting bias. Nearly every claim of the captured territory is matched by a counter-claim from government sources. Fatality estimates for those killed in battles are weak at best. There are, however, clues that allow us to state what is known, what is unknown, and which direction each movement appears to be heading.

What is Known: OLF-Shane

OLF-Shane is led by several commanders who are based in different parts of the Oromia region. When the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) decided to disarm in 2018, some commanders expressed distrust in the incoming federal government and chose to remain in remote hideouts in the Oromia region (The Economist, 19 May 2021). Since then, these commanders have labeled themselves the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA). The government uses the term OLF-Shane. OLF-Shane militants are most active in West Wollega, East Wollega, and Horo Guduru Wollega zones of western Oromia, as well as Guji and West Guji zones in southern Oromia.

OLF-Shane’s current rise in strength can largely be attributed to the fracturing of a youth protest movement known as the “Qeerroo.” Following a series of anti-government riots in 2019 and 2020, during which hundreds of non-Oromo minorities were killed by rioters in the Oromia region, Ethiopian government forces cracked down on Qeerroo youth, and thousands were arrested, along with leaders of the OLF and Oromo Federalist Congress (OFC). Accusing the government of eliminating political space and heavy-handed behavior, thousands of youth left the Qeerroo protest movement and fled to the remote hideouts of the OLF-Shane (Ethiopian Insight, 7 April 2021).

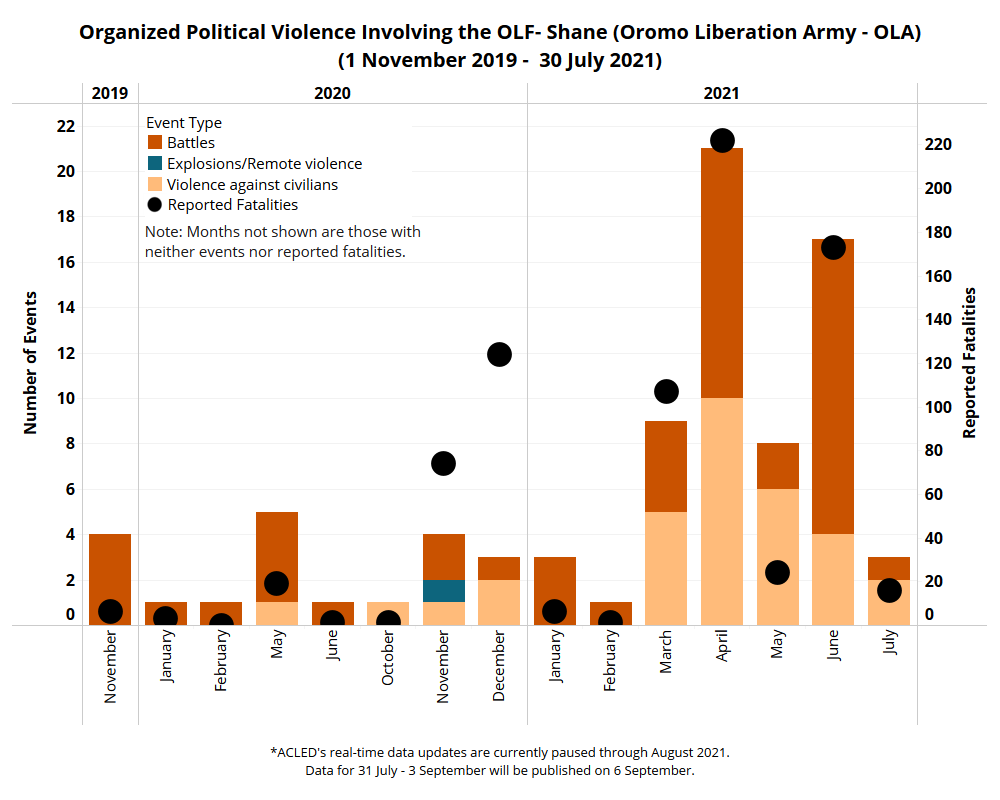

Since these crackdowns and arrests, battle events involving OLF-Shane have increased (see figure below). Territorial expansions by OLF-Shane include new areas of Guji, Jimma, Horo Guduru Wollega, East Wollega, and West Shewa. Most battles are fought against ENDF or the Oromo regional special police – whose mandate is specifically to counter violent insurgencies like the OLF-Shane. Efforts by the government to counter OLF-Shane appear to have increased since the group was legally declared a terrorist organization, with 16 battles and 170 battle-related fatalities recorded.

A key feature of the OLF-Shane insurgency is what appears to be a lack of internal cohesion and “discipline” failures, or at least a failure to properly control an area under their influence. This has directly or indirectly resulted in the death of civilians. In some locations of the Oromia region, the insurgents have been defined as a “potpourri of loosely connected militias rather than a full-fledged rebellion” (The Economist, 21 March 2020).

The natural result of this disorganization is a number of militias in the Oromia region that are associated (self-labeled or government attributed) to the OLF-Shane, but do not fall in line with the OLF-Shane command structure.

Attacks against civilians and attempted displacements are most frequent in areas of western Oromia, where thousands of ethnic Amhara and Tigre were resettled during the 1980s. Attacks against ethnic minorities occur on a weekly basis and hundreds of people have been killed as a result (Zelalem Teferra, 18 April 2010; BBC, 3 November 2020; Reuters, 29 April 2021; Addis Standard, 1 May 2021). While the government blames civilian killings on OLF-Shane militants, OLF-Shane official spokesmen deny responsibility, claiming instead that the attacks were conducted by a third party associated with the government (Addis Standard, 1 May 2021). Alongside violence against civilians, communal clashes fought between native Oromo and ethnic Amhara, many of whom were moved into areas of Oromia during the 1980s, have worsened as a result of a weakened security presence as the relative strength of the OLF-Shane grows.

The lack of access, ongoing instability, and heavy pressure on journalists by both the government and by OLF-Shane makes an independent investigation into violence against civilians impossible. Until a credible organization conducts an investigation, attributing the ongoing attacks to any specific actor dismisses the critical nuance involved in the Oromia region’s complicated conflict space.

What is Known: TPLF

The TPLF had dominated Ethiopian politics since coming to power as part of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) in 1991. Key to the TPLF’s success as an insurgent group has been their historical access to the country’s resources for the past three decades. This includes TPLF’s considerable hold over the federal forces of the ENDF. After four years of demonstrations against the TPLF-controlled EPRDF beginning in 2014, the TPLF lost its power over the federal government in 2018 was reduced to governing Tigray only. The TPLF then started to build up the Tigray regional special forces. In September 2020, it defied the federal government and held a regional election while the federal government postponed the general election for one year. Two months later, TPLF attacked federal troops based in the region (Africa News, 27 November 2021).

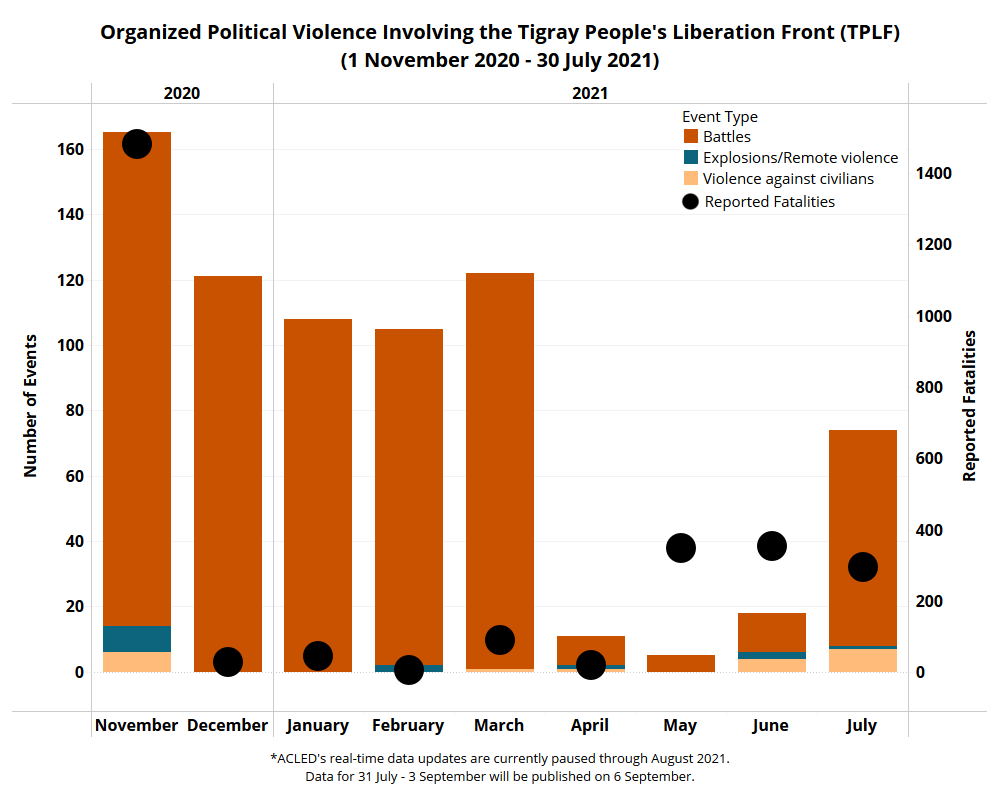

Violent conflict between the federal government and the TPLF erupted on 4 November 2020 as a result of an attack by the TPLF on the ENDF’s Northern Command (Reuters, 7 December 2020). Although the federal government was able to quickly beat the TPLF in conventional warfare (due to the involvement of the Eritrean army), its efforts to arrest all top political officers in the group quickly spiraled into a quagmire for federal troops as TPLF forces regrouped into an insurgency launched from the remote mountainous villages of the region (see EPO’s Tigray Conflict page). That insurgency has grown significantly since April of 2020 (see figure below).

On the ground, federal forces faced Tigray regional forces and local militias who were difficult to identify (New York Times, 30 June 2021). Ethiopian and Eritrean forces carried out mass killings of civilians (Ethiopian Human Rights Commission, March 2021). Sexual violence was rampant (Foreign Policy, 27 April 2021). A perception that the Ethiopian and Eritrean armies were present in Tigray to punish the region for supporting the TPLF led to the successful recruitment of many youths who were bitter about what was happening to their families (AP, 14 July 2021).

The ENDF took heavy losses while Ethiopia’s top officials were crippled by diplomatic pressure — including sanctions — over the involvement of Eritrean troops and civilian targeting (BBC, 29 June 2021; EBC 3 July 2021). Frustrated and facing an impending humanitarian and military disaster, the government decided to withdraw from the region on 28 June 2021 (Amhara Media Corporation, 28 June 2021).

Since then, the TPLF has continued to expand into Afar and northern Amhara regions, sparking a new level of concern throughout Ethiopia. Regional governments throughout the country have issued calls for youth to mobilize and combat the TPLF’s recent expansions (BBC Amharic, 26 July 2021; BBC Amharic, 25 July 2021; Ethiopia Broadcast Corporation, 26 July 2021). TPLF spokesperson Getachew Reda boasted that Tigray fighters could advance deeper into the Amhara region toward Gondar and Debre Birhan if they continued to face “ill-trained peasant militias” (Getachew K Reda, 24 July 2021).

Clashes in Afar have also resulted in territorial gains by the TPLF. According to Afar and Amhara regional officials, TPLF forces now control significant territory within both Afar and Amhara regional states (Reuters, 22 July 2021). Thousands of people have been displaced (VOA, 3 August 2021).

The TPLF’s ultimate goal in attacking the Afar region is to prevent the ENDF from regrouping in Semara, the capital of the region, and for the group to control the Ethiopia/Djibouti supply line. The Ethiopia/Djibouti transport corridor is a paved road that connects the country’s capital to seaports in Djibouti for the import of fuel and food. Even though TPLF forces are still hundreds of kilometers away, the road was blocked for days by protesters from the Somali regional state who are denouncing recent attacks by gunmen and special forces from the Afar region on Garba Issa, Undhufto, and Aydetu towns (Addis Standard, 27 July 2021; Somali Region Communication, 26 July 2021). See the EPO’s Afar-Somali border conflict page for more information on historical disputes over contested territory along the Ethiopia/Djibouti highway.

Advancements by the TPLF in July have indicated a new phase in its development, showcasing a transformation of the TPLF strategies from insurgency tactics to more formalized warfare using captured heavy weapons and rapid advances along major transportation arteries. Regional special forces — which are trained and equipped to combat insurgencies in their home regions — are unlikely to be very effective against such tactics and are at a major disadvantage.

The TPLF’s ability to organize and manage both its own internal structure and its absorbed militia forces is its greatest enabling factor. Its military success can be attributed to individuals within the organization with a vast amount of experience (BBC, 1 July 2021).

Yet, until the TPLF is able to control a route connecting Tigray to the outside world, the viability of further sustaining the insurgency at its current rate is doubtful. It has been fenced in by the ENDF, Amhara, Afar, other regional and Eritrean forces geographically and thus blocked from importing fuel or weapons. Politically, the group remains tightly in control of the region’s elites, illustrated by the government’s complete failure in providing an alternate administration through interim officials. However, TPLF’s technical capacity to provide electricity, fuel, food, and security has been effectively diminished. Tigrayans have been in the dark since the TPLF took control in the last days of June. Without a change in the current status quo, the TPLF has no capacity to provide for its population.

What is Unknown

Information blackouts, internet cuts, a polarized society, and persecution of independent journalists have resulted in a very difficult information environment in Ethiopia. There are many unknowns that surround the two insurgencies, some of which are critical in assessing the government’s ability to maintain control over the country. What is unknown, and how it affects attempts at analysis, is discussed below.

The count of fighters, weapons, and funds are all very difficult to accurately estimate for both the TPLF and for OLF-Shane. For the OLF-Shane, there are likely many thousands of youth who have been recruited and trained to fight, although how many remain active is unclear. Similar issues exist when attempting to assess the strength of the TPLF. While the group started with an estimated 250,000 thousand fighters, how many were lost in the initial stages of the conflict and how many have been recruited and trained since then is unknown (Reuters, 13 November 2020).

The extent of territorial control by OLF-Shane is likewise fluid; it is not clear either how ready they are to engage in local governance. Due to the generally remote nature of the OLF-Shane’s area of operations, as well as the lack of independent media to report on the western Oromia conflict, exactly which locations are controlled by the group is information tightly controlled by local actors.

OLF-Shane forces have recently claimed control over several kebeles in the Guji zone, including the Gumi Eldalo and Liben districts (OLA Communique, 15 August 2021). Zone level administrators say that the claims are false, although they admit there are security issues that need solving (Guji Zone Communication Affairs Office, 10 August 2021). Interviews with residents and hospital staff in the contested areas indicate that the militants do hold territory (BBC Amharic, 18 June 2021).

Further, the extent of both organizations’ abilities to engage with outside actors for support is unclear. The Oromo and Tigray ethnic groups have large and powerful diaspora communities residing in Europe and North America who have historically played important roles in Ethiopia’s internal political conflicts (DW, 17 July 2020). How effective those diaspora who oppose the government are in circumventing barriers set up by the federal government to support insurgencies by financial or other means is not known.

Moreover, both groups will likely attempt to establish external relationships with potential allies — namely Sudan and Egypt — to allow the flow of weapons and cash. Sudan’s willingness to allow this to happen is not entirely clear. Neither insurgent group supports a policy that abandons the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam project. What is clear, however, is that both groups will attempt to exploit Sudan’s porous eastern border to establish links to the outside world.

Links between OLF-Shane and the TPLF are likewise unclear, although recent developments suggest that the two groups are coordinating on some level (AP News, 11 August 2021). The fighters who make up the OLF-Shane consist of aged men, who have spent their lives combatting TPLF forces, and also Oromo youth, who have suffered arrests, beatings, and killings at the hands of the TPLF’s infamous “Agazi” squads – a special force unit loyal to the TPLF who often operated independent of local law enforcement (Global Security, 8 April 2016). While they are currently aligned in their efforts to defeat Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and are often accused by government sources as acting in collaboration, their historical differences make a sustainable partnership unfeasible.

Which Direction the Insurgencies Appear to be Heading

Both OLF-Shane and the TPLF have increased their military and governance capacity during the recent year. Both make significant claims about “popular support” within their respective operation theaters, although said claims are often overshadowed by internal reports of intimidation and threats for compliance.

The TPLF has recently transformed from an insurgent movement based on guerilla tactics to fighting conventional warfare with large weapons and tanks. The OLF-Shane remains an insurgency movement that holds little territory and instead prefers to attack and retreat quickly after each encounter.

The OLF-Shane has recently increased its public relations capabilities and wants to appear as a professional organization capable of governance and external relations. A recent incident where employees of a mining company were taken captive in western Oromia provides a prime example of this (Oromia Media Network, 17 June 2021; Addis Standard, 15 May 2021). The miners were released through an international organization through a process paraded by the OLA as an example of its newly-found capacity to engage with non-state organizations. OLF-Shane militants have also been taking captives following battles with Oromia regional state forces (militia and special forces), suggesting capabilities to hold and negotiate prisoner swaps. These capabilities appear to be new and increasing.

Along with the insurgency against federal forces, OLF-Shane militants have been accused of targeting ethnic minorities in brutal attacks throughout western Oromia, and of being involved in clashes fought against the Amhara regional special police in areas surrounding Ataye city (see EPO’s Kemise conflict page). OLF-Shane official spokespersons categorically deny both accusations and point instead toward government-associated militias. Whoever is responsible, it appears that areas, where OLF-Shane is influential, are sliding into disorder as government forces lose their grip on security and the OLF-Shane either will not or cannot, replace it to prevent attacks against vulnerable populations.

While the OLF-Shane also appears to be gaining some ground, the ability of the Oromo state forces to prevent violence during the electoral period was impressive and indicates a strong apparatus capable of standing up against the militants. See more of the EPO’s election analysis in these weekly reports (EPO Weekly: 19-25 June 2021; EPO Special Report: Ethiopia’s Election and Abiy’s political prospects, 10 June 2021 ).

Both the TPLF and the OLF-Shane appear to be taking on a similar strategy of making the governance of geographical areas under federal control an impossibility. This is hugely expensive for the federal government and results mostly in the suffering of civilians who cannot access services available to other citizens of the country (Addis Standard, 27 March 2020, Washington Post, 2 July 2021). While effective in gaining local support in the short run, this strategy will quickly spoil any local support either group commands as civilians begin demanding the goods and services that militant groups cannot provide. Until either group is able to gain real governance capacity — i.e. turning on the lights and keeping fuel stations full — civilian populations in areas under their influence will suffer.