IN THIS REPORT

- January at a Glance

- Vital Trends

- Key Events in January

- Monthly Focus: The Information Landscape in Ethiopia

January at a Glance

VITAL TRENDS

- ACLED records 92 political violence events and 236 reported fatalities in January. All event types decreased from December, except for battles, which increased by 103% from December, while battle-related fatalities increased by 7%.

- Oromia region had the highest number of reported political violence events, at 50, while Amhara region had the highest number of reported fatalities, at 142. This contrasts with the previous three months, where most events and fatalities were recorded in Oromia.

- In January, the most common event types were battles, with 65 events, and violence against civilians, with 25 events. Most battles were between the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF)-Shane and government forces, while 13% were between Oromo ethnic militias and Amhara regional special forces.

KEY EVENTS IN JANUARY

Monthly Focus: The Information Landscape in Ethiopia

After coming to power in 2018, reforms implemented by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed initially resulted in greater press freedoms in Ethiopia. Abiy removed bans on over 250 media outlets and freed dozens of jailed journalists.1Maggie Fick, ‘In Abiy’s Ethiopia, press freedom flourished then fear returned,’ Reuters, 28 May 2021 Banned media outlets – such as the diaspora-run Oromia Media Network (OMN) and Ethiopian Satellite Television (ESAT) – expressed confidence in Abiy’s reforms and established offices in Addis Ababa.2Freedom House, ‘Freedom in the World 2020: Ethiopia,’ 2020; for more information on the banning of OMN and ESAT, see Addis Fortune, ‘Command Post Forbids Watching ESAT, OMN,’ 18 October 2016

Political violence, riots, and multiple insurgencies against Abiy’s government have since challenged the prime minister’s liberalization agenda. Government pressure, increased polarization, and access constraints for conflict areas have resulted in a more restricted information environment, which varies across the country. The number of distinct media voices and sources has decreased since 2019; journalists have been arrested, deported, and harassed, limiting their ability to provide coverage for both domestic and international audiences; media have increasingly reflected the polarized nature of their audiences; and bias in the coverage of individual events has increased.3Declan Walsh, ‘Ethiopia Expels New York Times Reporter,’ New York Times,’ 20 May 2021; Committee to Protect Journalists, ‘Ethiopia expels Economist correspondent Tom Gardner,’ 16 May 2022 Meanwhile, some regions are ‘media deserts’ without accessible public channels to report on activity. Other regions, including those with active conflicts, have suffered from limited coverage due to media, communication, and electricity blackouts, as well as access constraints linked to security risks.4Associated Press, ‘Ethiopia offers no date for end to blackout in Tigray region,’ 29 November 2022

The overall consequences have been:

- A lack of thorough and accurate information about political violence and disorder generally across Ethiopia. This leads to insufficient detail about violent events, the parties involved, and their outcomes.

- A proliferation of biased information, misinformation, and disinformation from sources often located outside conflict zones and outside Ethiopia. In the absence of reliable information, one-sided accounts of conflict omit relevant factors that could legitimize the ‘other side.’ These sources fill information vacuums, generating echo chambers, hate speech, and harassment, which undermines verification efforts and attempts at accurate and objective reporting. This creates broader mistrust of conflict information due to perceptions of misleading biases and a lack of robust triangulation.

- A need to continue developing the information environment to safeguard press freedom and establish space for unbiased and robust incident documentation.

How do ACLED-EPO researchers code events and reported fatalities in this information environment?

EPO researchers review sources in English, Amharic, Somali, Tigrigna, and Afaan Oromo languages each week to code political violence and demonstration events in Ethiopia, in addition to information gathered from local partners. The methodology that ACLED and the EPO use to collect information has remained stable and is consistent with ACLED’s approach toward data collection worldwide.

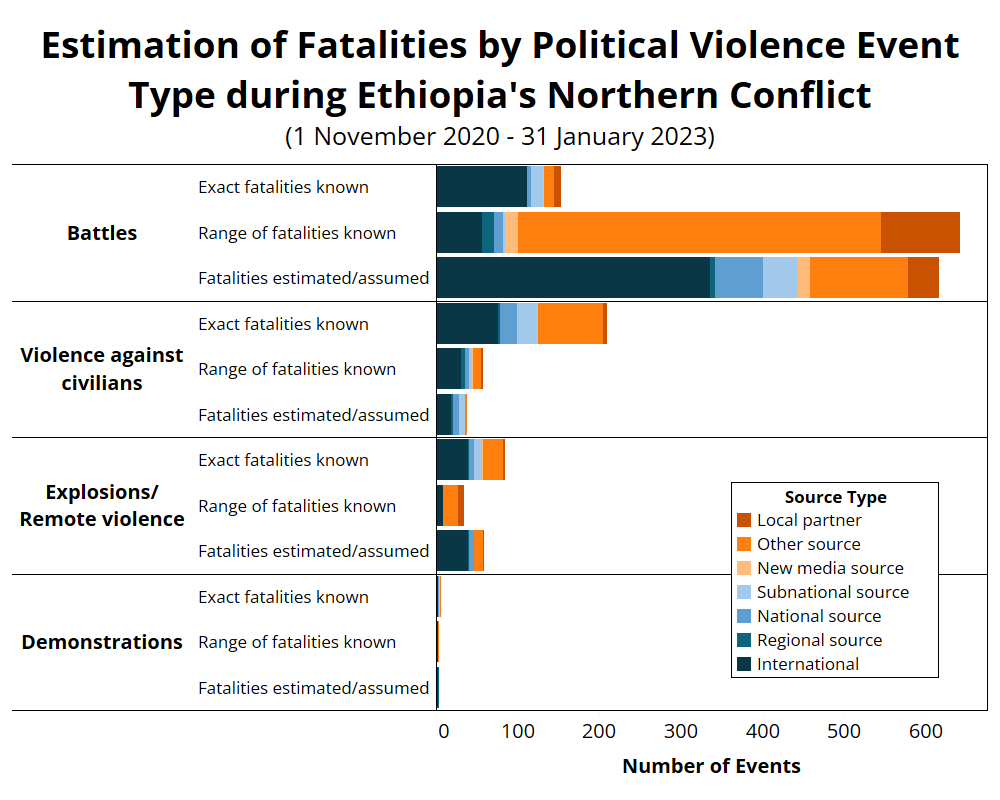

Tracking fatalities is one of the most difficult aspects of conflict data collection in general, as fatality counts are frequently the most biased, inconsistent, and poorly documented components of conflict reporting, and this is especially true of active conflict environments impacted by high levels of mis/disinformation and severe access constraints. ACLED and EPO therefore take a conservative approach to fatality recording. if an event source does not reference fatalities, none are recorded. If a source mentions an unspecified number of fatalities, researchers consider where the event occurred and who was involved, and an estimate of three or 10 fatalities is coded depending on the circumstances of the event. For example, in an intense war zone where the event is more likely to have a high death toll, 10 fatalities are coded. In a low-conflict zone where the circumstances point to a death toll likely less than 10, a more conservative estimate of three fatalities is coded. If a source mentions a range of possible fatalities, the lowest number is recorded unless more information is available to substantiate a higher estimate. If a source includes a broad estimate like “hundreds of deaths,” and no additional information is included, 100 deaths are recorded for the event. If a reliable source confirms a range of accumulated direct deaths from a conflict, it is possible to distribute the average additional deaths to events in which these fatalities would have occurred (for more information, see FAQs: ACLED Fatality Methodology). For example, if it is eventually confirmed that thousands of soldiers have died in the two-year conflict in the north on aggregate, then the collected events for which no reliable fatality information was previously available, or those with an approximate fatality estimate, will be amended to include an average distribution of fatalities according to the verified source. The amendments are made directly to the event data, noted publicly, and new pattern analysis is released.

Every ACLED event is associated with an acknowledged source. These sources are typically known, public, and open, with the addition – where necessary – of local, private sources. ACLED depends on these sources to produce an accurate description of political disorder events, and gauges the bias and robustness of sources through a rigorous assessment before inclusion. While conflict zones can produce highly biased sources, relevant information can be selectively extracted from such sources and gathered to reduce the impact of source biases and retain event information (for a recent discussion of bias in conflict data, see An Agenda for Addressing Bias in Conflict Data).

Often, standard rules around controlling the most biased parts of a report can lead to underreported fatalities, as fatalities are the most biased feature of event data (for more information, see FAQs: ACLED Fatality Methodology). They are subject to biases of exaggeration for media interest, reporter estimation bias, and source bias (i.e., which side of the conflict the information came from). For example, the Taliban had an active reporting service during its period as insurgents in Afghanistan (for more details, see The World According to the Taliban: New Data on Afghanistan). This service often reported information similar to other Afghan sources for decisive events and battles with government forces, and also reported on the specific nature of small skirmishes. Yet, this source tended to report distorted fatality numbers that were largely sustained by government forces. As such, the fatality information was biased, but the event information was reliable.

How do ACLED and EPO address aggregated conflict fatality totals?

The conflict in northern Ethiopia has been labelled by some international media reports as the world’s “deadliest war.”5Bobby Ghosh, ‘The World’s Deadliest War Isn’t in Ukraine, But in Ethiopia,’ Washington Post, 23 March 2022 Estimates of civilian fatalities range from 300,000 to 800,000 from November 2020 to 2022. The variation in this number is an example of an aggregated conflict fatality assessment. Such assessments are typically subject to debate.

To explain how ACLED and EPO deal with such aggregated totals, it is necessary to begin from these points:

- ACLED works from the event (and its source) up, rather than from a total number of events and fatalities down. This means that information is sought and collected on specific incidents, not to support a high number from aggregated accounts. It is very rare that large aggregated fatality totals are substantiated with events and evidence for constituent incidents.

- Large fatality estimates that differ widely are a feature of many intense conflicts. These estimates are not correlated with poor reporting or exclusively low-information environments. High fatality totals reflect different forms of direct and indirect deaths. Often, accounts by journalists, human rights organizations, and other research entities will include estimates of indirect deaths (including those resulting from a lack of healthcare, malnutrition, etc.) in addition to deaths directly caused by political violence.

In most cases, the total direct fatalities from political violence are substantially lower than the estimated indirect fatalities. Studies on fatalities from direct violence in several active war zones include estimates far lower than those publicly associated with conflicts. Consider the accounting for wars in the post-9/11 period, including direct war deaths in Afghanistan and Pakistan (2001-21), Iraq (2003-21), Syria (2014-21), Yemen (2002-21), and additional conflict areas, according to the Costs of War project at Brown University’s Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs. The project holds that “at least 929,000 people have died due to direct war violence, including armed forces on all sides of the conflicts, contractors, civilians, journalists, and humanitarian workers.”6Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, ‘Costs of War,’ September 2021; see also Daniel Brown & Azmi Haroun, ‘The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have killed at least 500,000 people, according to a report that breaks down the toll,’ Business Insider, 26 August 2022 Further, consider extensive real-time documentation and ongoing debates around fatalities during the Ukraine conflict, where very high numbers are presented as estimates from external sources.7Olivier Knox, ‘Russia has lost up to 80,000 troops in Ukraine. Or 75,000. Or is it 60,000?,’ Washington Post, 9 August 2022; see also Helene Cooper, Eric Schmitt, & Thomas Gibbons-Neff, ‘Soaring Death Toll Gives Grim Insight Into Russian Tactics,’ New York Times, 2 February 2023, as American officials note that all casualty numbers are estimates that could be higher or lower. Additional accounts refer to the difficulties of reporting in combat environments to explain the inability to determine a clear accounting of events, outcomes, and fatalities.8Dan Lamothe, Liz Sly, & Annabelle Timsit, ‘‘Well over’ 100,000 Russian troops killed or wounded in Ukraine, U.S. says,’ Washington Post, 10 November 2022. *Reports of fatality numbers from Ukraine from the perspective of the United States military, which were denied by the Ukrainian military and the Russian military.

The full accounting of conflict is often exaggerated in the beginning of hostilities, and parsing direct deaths from indirect is difficult in practice. Further, while methods to estimate conflict-related deaths from extrapolation of sampled communities9Baruch Fischhoff, Scott Atran, & Noam Fischhoff, ‘Counting casualties: A framework for respectful, useful records,’ Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 2007 are debated, they are largely not possible to confirm or refute. For instance, as of 2007, some reports estimates indicated there were 5.4 million “excess” fatalities in the Democratic Republic of Congo related to its ongoing conflict.10Benjamin Coghlan, Pascal Ngoy, Flavien Mulumba, Colleen Hardy, Valerie Nkamgang Bemo, Tony Stewart, Jennifer Lewis, & Richard Brennan, ‘Mortality in the Democratic Republic of Congo: An ongoing crisis,’ International Rescue Committee, 1 May 2007 This estimate was based on extrapolation,11Two strata in the country were studied using a three-stage, household-based cluster sampling technique. Results from the clusters were extrapolated to form aggregate fatality estimates. and deemed to be a considerable overestimation of excess deaths from surveys based on population loss.12Benjamin Coghlan, Pascal Ngoy, Flavien Mulumba, Colleen Hardy, Valerie Nkamgang Bemo, Tony Stewart, Jennifer Lewis, & Richard Brennan, ‘Mortality in the Democratic Republic of Congo: An ongoing crisis,’ International Rescue Committee, 1 May 2007; Richard Tshingamb Kapend, ‘The demography of armed conflict and violence: assessing the extent of population loss associated with the 1998–2004 D.R. Congo armed conflict,’ University of Southampton Doctoral Thesis, 2014 Upon further reading, only 10% of those deaths were directly or indirectly associated with conflict, while the vast majority were due to health issues. Yet, reports on conflicts sometimes aggregate all preventable deaths into an aggregation of ‘conflict-related deaths,’ which leads to high numbers.

Is the 600,000 civilian fatality estimate for Tigray substantiated?

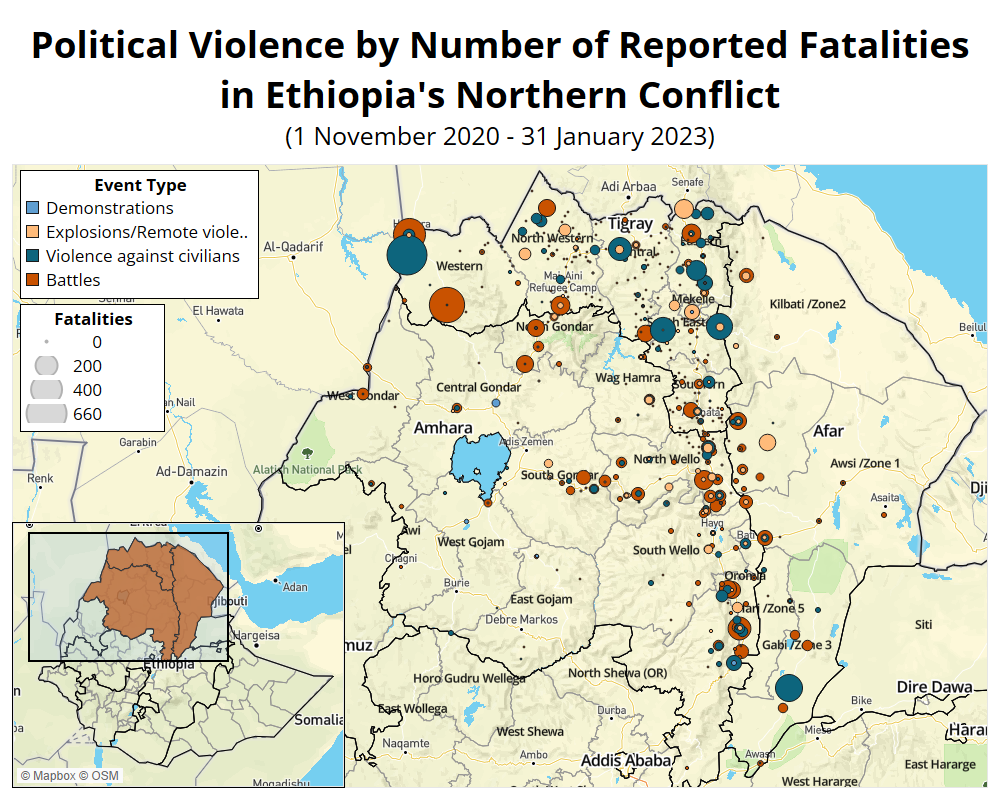

African Union envoy Olusegun Obasanjo noted an estimate, in an interview with the Financial Times, that 600,000 people might have died during Ethiopia’s civil conflict over the past two years.13David Pilling & Andres Schipani, ‘War in Tigray may have killed 600,000 people, peace mediator says,’ Financial Times, 14 January 2023 This number and other large aggregate estimates for the fatalities for the Tigray conflict are not similar to the estimates derived from recorded events in the ACLED dataset. ACLED has recorded 1,905 political violence events and 9,861 reported fatalities in Tigray, Afar, and Amhara regions from 1 November 2020 to 31 January 2023 (see map below). ACLED estimates that, overall, one in every four Ethiopians14This estimate is from an ACLED-World Pop collaboration to determine conflict exposure. The one-in-four estimate refers to the number of Ethiopians within five kilometers of the location of at least one event of armed, organized political violence that caused fatalities during 2021. has been exposed to armed, organized, fatal political violence in the past year. Nevertheless, ACLED’s estimate is not close to the commonly referenced 600,000 number. Why not?

According to a study led by Professor Jan Nyssen of the University of Ghent, “calculations of the total number of civilian deaths in Tigray, updated up to 31 December 2022, lead to an average estimate of 518k civilian victims in Tigray,” with the lowest estimate “311k,” and the highest “808k.” Further, “approx. 10% would be due to massacres, bomb impacts and other killings, 30% due to the total collapse of the healthcare system, and 60% to famine.”15Jan Nyssen, ‘Documenting the Civilian Victims of the Tigray war,’ Webinar organized by the Royal Holloway Centre for International Security & Every Casualty Counts, 19 January 2023; Jan Nyssen, ‘Webinar: Documenting the Civilian Victims of the Tigray War,’ Every Casualty Counts, 19 January 2023 Based on these estimates, 31,100-80,800 are direct deaths from violence, while the remainder is classified as indirect deaths. It is unknown which methods were used to produce the estimates, as typical interpolation (estimation) techniques require samples and surveys of health centers, camps, and other conflict-affected areas to ascertain the number of total fatalities. No known surveys or samples are provided as evidence for these numbers. This information used is noted to be sourced from citizen reporting and key informants, semi-structured interviews, and telephone interviews with survivors in addition to regional, national, and international administrators, diplomats, and journalists.16Jan Nyssen, ‘Webinar: Documenting the Civilian Victims of the Tigray War,’ Every Casualty Counts, 19 January 2023 However, given the difficulties in accessing or extracting information from Tigray, specifically since November 2020, details of how information is collected and verified is unclear.

The public direct death fatality totals for the Tigray conflict are associated with the Every Casualty Counts project through the Ethiopia: Tigray War site.17Ghent University & Every Casualty Counts, ‘Ethiopia: Tigray War, About Us,’ 2023 This website records 435 incidents and an estimated 8,081-15,414 “deadly victims” across 445 incidents,18Ghent University & Every Casualty Counts, ‘Ethiopia: Tigray War, Incidents,’ 2023 with the casualty database populated by a mix of sources including social media posts, media reports, and advocacy group listings.19Ghent University & Every Casualty Counts, ‘Ethiopia: Tigray War, Methodology’ From this site’s records, the 31,100-80,800 estimate of direct civilian deaths is not substantiated with further information, and the estimate of 600,000 deaths is neither confirmed nor refuted.

Additionally, the 600,000 estimate pertains only to Tigray civilians, without including fatalities incurred by Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) forces, the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF), the Eritrean Defence Force (EDF), Amhara and Afar militias, and Amhara or Afar civilians. Reporting on civilian deaths in Amhara and Afar regions was not subject to the same restrictions as in Tigray. Several reports, some by universities in the region, accounted for the civilian toll soon after extensive fighting took place.20Amhara Media Corporation, ‘A study on the outcome of the terrorist TPLF invasion in Amhara region released,’ 29 September 2022 These reports focused on direct deaths. There remains a lack of reliable information on fatalities among fighting forces, however. Some Ethiopian officials have suggested around 80,000 or 100,000 for total direct deaths,21David Pilling & Andres Schipan, ‘War in Tigray may have killed 600,000 people, peace mediator says,’ Financial Times, 14 January 2023 similar to the 1998-99 Ethiopia and Eritrea conflict in the region around Badme. However, no information is known to exist to estimate, extrapolate, or explain Eritrean fatalities – both from the EDF and civilians killed by the EDF – throughout the conflict.

According to a report by Reyot Media, up to 254,000 ENDF fighters were killed in the two-year conflict.22Reyot Media, ‘254 thousand troops were neutralized – Birhanu Jula,’ 27 January 2023 This number, claimed to have been stated by the ENDF’s Chief of General Staff Birhanu Jula, is unconfirmed at the time of writing, and again, represents an aggregate number of direct deaths. The ENDF and associated militia recruits, and TPLF forces, are likely to have sustained the highest number of direct fatalities during the conflict. It is important to ascertain and verify the number of fatalities incurred by armed groups.

Opportunities are present to collect unbiased, robust, and thorough studies assessing the impacts of the violence between and upon all parties in the northern conflict, including for human rights organizations in Ethiopia and elsewhere. This would require a multilingual survey team, updated localized population estimates, a study of satellite imagery, and a mandate from administrations in the three affected regions – Tigray, Amhara, and Afar – and the federal government.

What about other areas in Ethiopia?

As the conflict in northern Ethiopia has subsided with the signing of the permanent cessation of hostilities agreement in November 2022, the focus has turned to Oromia region. Characteristics of the northern Ethiopia conflict included battles involving thousands of individuals and heavy military equipment like tanks, artillery, and drones. In contrast, the OLF-Shane (also known as the Oromo Liberation Army) insurgency has been fought with small units of fighters, rarely involving artillery or other heavy weapons. Yet, this conflict has also been deadly. ACLED records 5,741 reported fatalities from events involving the OLF-Shane since the group split from the OLF in April 2019.23Dawit Endeshaw, ‘OLF Politics, Military Splits,’ The Reporter, 6 April 2019

The information space in Oromia region is significantly different from that in Tigray region. Oromia’s geographic placement at the center of Ethiopia renders information blackout attempts less effective. Rather, bias is a more pressing issue in the Oromia information landscape. While fatality counts are the most biased feature of conflict event data generally, actor attribution is also widely disputed for the conflicts in Oromia. Various narratives regarding the violence in East Wollega zone in Oromia, as well as in North Shewa and Oromia special zones in Amhara region, are prime examples of this contestation. In Amhara, violence that erupted at the end of January featured conflict between ethnic Oromo and Amhara communities in one of the most contested parts of Ethiopia. Amhara regional authorities blamed “anti-peace groups” for the violence,24Amhara Media Corporation, ‘Press statement on current issues by Amhara national regional government,’ 24 January 2023 while local Amhara residents named OLF-Shane as being the perpetrator.25Eshete Bekele, ‘According to local officials 98 farmers have been killed in Oromia ethnic administrative zone only,’ Deutsche Welle, 28 January 2023 OLF-Shane authorities denied being active in the area and instead accused Amhara regional security forces of attempting “ethnic cleansing against the Wollo Oromo”26Oromo Liberation Army, ‘Ethnic Cleansing underway in Wollo against Oromo Civilians,’ 25 January 2023 (see EPO Weekly: 21-27 January 2023 for more information on the various narratives surrounding violence in Amhara region during the last week of January).

One reason for the difficulties in actor attribution in Oromia is the fluid nature of the armed groups involved in the violence. The OLF-Shane is fraught with factionalism. In some cases, splinter groups, criminal gangs, and ethnic Oromo youth carry out violence, claiming to be members of the OLF-Shane without having official links to the group. Similarly, Fano militias, also involved in violence in Oromia, lack an official command structure, and defining the boundaries of who Fano militias are can be challenging (see EPO December 2022: Conflict Expands in Oromia Region for more details on actors in Oromia region).

To mitigate these issues, ACLED-EPO researchers draw from multiple sources in different languages to build a picture of events as they occur. Taking into account multiple angles of an event is critical for providing a comprehensive and accurate dataset, though some ambiguity does exist in terms of actors such as Fano militias or even the OLF-Shane in locations like Oromia special zone of Amhara region.

In Benshangul/Gumuz region, the information environment is severely restricted due to a lack of infrastructure and coverage by the media, and the political relevance of the region. Besides representation in local governments, Indigenous groups in Benshangul/Gumuz exert little influence over national political affairs.27Tom Gardner, ‘All Is Not Quiet on Ethiopia’s Western Front,’ Foreign Policy, 6 January 2021 The region is peripherally located, marginalized politically, and severely underdeveloped. With the exception of the recently completed Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, the region contributes little to the national economy.

In addition to challenges in coverage as a result of poor infrastructure, biases are also problematic. Ethnic Amharas who have settled in Benshangul/Gumuz’s Metekel zone are politically marginalized in Benshangul/Gumuz region due to the Ethiopian constitution’s ethno-federalist tenets.28Tsegaye Birhanu, ‘Ethiopia: Is Metekel the next battleground after Tigray,’ Awash Post, 24 August 2021 While violence targeting ethnic Amhara civilians in Benshangul/Gumuz is well-documented by Amharic media outlets in the country, violence targeting members of Indigenous groups is not well-covered in national media, creating an imbalance of reporting and greater potential for bias. ACLED-EPO researchers collect data in Benshangul/Gumuz region taking into account known biases due to the political positioning of the region.

In summary, most conflict environments are already low-information spaces, as the identity of perpetrators, victims, and the intensity of violence and its outcomes are difficult to accurately ascertain in real time. ACLED builds event and fatality totals from discrete, individual events. Incident information is derived from known and trusted sources, but even so not all information provided by sources is wholly accurate or without bias. In these cases, ACLED requires further verification and triangulation. In addition to these information safeguards, ACLED uses conservative fatality measures, as conservative estimates have proven to be less biased than larger fatality assessments across conflicts, periods, and countries.

Reliable approaches to low-information conflict environments include fostering local sources and stringer networks, and amending collected information when more accurate reports become available. Information environments can also suffer from biased or contradictory reporting (including propaganda, disinformation, and factual limitations). As noted above, even in such cases, select information may be usable if triangulated. Information on fatality numbers and which actors instigated conflicts or suffered casualties tends to be the most biased aspects of these reports.

Even by conservative measures, the northern conflict sets Ethiopia among the deadliest countries in the world in 2021 and 2022 (see ACLED’s Conflict Severity Index in which Ethiopia features highly on both the deadliness and danger indicators, as well as ACLED’s Year in Review: 2022). Notwithstanding, the extent of the violence and its direct effects have not yet been fully and widely accounted for. When additional reports emerge from the multiple ongoing efforts to determine the losses across communities in the north, ACLED-EPO will triangulate, record, and update those incidents and fatalities, as specified in the dataset’s methodology.

Data additions

ACLED collects data in real time, but it is also a ‘living dataset,’ meaning that data are subject to updates, corrections, and additions on a weekly basis as new or better information emerges. Regular reviews are undertaken as more information is published and facts are established about historical conflict events. In the case of Tigray, information blackouts during the conflict made gathering and verifying information very difficult. As government services are restored and access constraints are reduced, it is expected that additional information will be made available, verified, and added to the historical dataset.

Complexities in Ethiopia’s information environment highlight the need for professional, unbiased conflict reporting. Obstruction by government forces and armed groups to media hinder accuracy and encourage extrapolation. The ACLED-EPO team urges relevant organizations to prioritize accuracy and reduce bias so that full and comprehensive accounts can be developed.