EPO Monthly Update | January 2024

Ethiopia’s Quest for Sea Access

January at a Glance

VITAL TRENDS

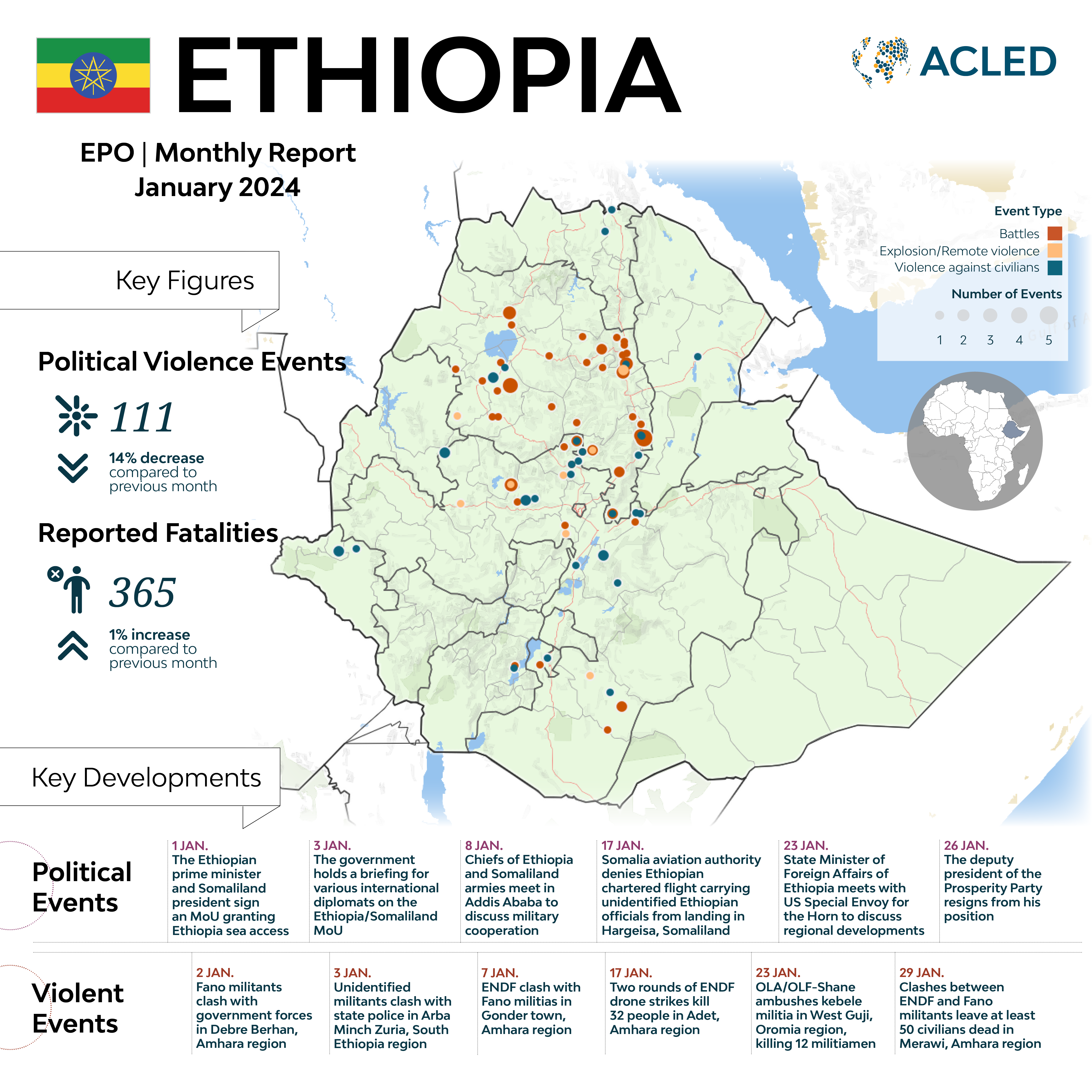

- In January, ACLED records 111 political violence events and 365 reported fatalities in Ethiopia.

- Political violence decreased in January. Battles and violence against civilians were the two most common event types, with 69 and 33 events, respectively.

- ACLED records the most political violence in January — 66 events and 242 reported fatalities — in Amhara region. Clashes between Fano militia and government forces, which have been fighting since August, accounted for 68% of the events in the region.

KEY DEVELOPMENTS

Ethiopia’s Quest for Sea Access

The new year began with the signing of a memorandum of understanding (MoU) between Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and the President of Somaliland, Muse Bihi Abdi. The MoU stipulates that Ethiopia can lease a 20-kilometer coastline near Luqhaye and Saylac (Zeila) towns in Somaliland’s Awdal region for 50 years to build its naval base. In exchange, Somaliland would receive a stake in Ethiopian Airlines and formal recognition as a sovereign country.1Faisal Ali, ‘Ethiopia and Somaliland reach agreement over access to ports,’ The Guardian, 1 January 2024; Guled Kassim, ‘Balancing Ambitions: Somaliland’s Economic Pursuits and the Controversial Ethio-Somaliland Memorandum of Understanding,’ Somaliland Current, 15 January 2024 According to the Somaliland president, for imports and exports, Ethiopia will be using the Berbera port.2 X @MadaxtooyadaJSL, 25 January 2024 The signing of the MoU has ignited diplomatic tensions across the Horn, and it was met with criticism inside Somalia and abroad. The Somali government demanded that Ethiopia respect the country’s integrity and withdraw from the deal.3Harun Maruf, ‘Somalia rejects Ethiopia sea access deal with Somaliland,’ Voice of America, 2 January 2024 Regional and Western countries, as well as international organizations, condemned the deal, reaffirming their support for Somalia’s territorial integrity and calling for dialogue between Ethiopia and Somalia.4Faisal Ali, ‘Somalia ‘nullifies’ port agreement between Ethiopia and Somaliland,’ The Guardian, 6 January 2024

Following the end of the northern Ethiopia conflict in November 2022, the Ethiopian government sought to redress its diplomatic relations with Western countries. The signing of the MoU with Somaliland is a departure from this track. The reaction toward the MoU and the tension is mainly linked with four aspirations — Ethiopia’s aspiration to regain sea access, Somaliland’s aspiration for official recognition, Somalia’s aspiration to create a unified Somalia, and various actors’ geopolitical aspirations in the Red Sea. The interplay among these intertwined inspirations will determine whether this MoU will be translated into a binding deal that would end Ethiopia’s landlocked status.

Charting the Course to Regain Sea Access

Ethiopia has been landlocked since Eritrea gained independence in 1993 through a referendum. Djibouti has served as Ethiopia’s main seaport, processing approximately 90% of its import and export needs since the conflict between Ethiopia and Eritrea erupted in 1998.5Ethiopian News Agency, ‘Ethiopia’s Trade, Investment Flow to Djibouti Significantly Growing Over Past Three Years: Ethiopian Ambassador,’ 11 January 2024; The New Humanitarian, ‘Accord signed to use Djibouti port,’ 15 April 2002 Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has expressed his aspiration to secure sea access for Ethiopia since coming to power in 2018.6Fana Television, ‘Prime Minister Dr. Abiy Ahmed’s conversation with the leaders of the defense army part two,’ 11 June 2018 Yet, in October 2023, during a speech in Ethiopia’s House of Peoples’ Representatives, Abiy stated that the Nile River and Red Sea were of “existential” importance for Ethiopia and, without them, Ethiopia could not achieve “prosperity.”7Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation (EBC), ‘From the drop of water to seawater,’ 13 October 2023 He also reaffirmed Ethiopia’s interest in negotiating with neighboring countries in order to gain sea access. Following these statements, neighboring Eritrea, Djibouti, and Somalia rebuffed Ethiopia’s claims and rejected any negotiations on the issue.8Alain Amharic, ‘The Eritrean government said that the talks about the sea gate are confusing,’ 16 October 2023; Simon Marks, ‘Somalia Rebuffs Ethiopia’s Bid to Gain Direct Access to Red Sea Port,’ Bloomberg, 17 October 2023; Simon Marks, ‘Djibouti Latest Nation to Reject Ethiopia’s Red Sea Access Plea,’ Bloomberg, 19 October 2023

Before signing the MoU with Somaliland, Abiy’s government took several steps to strengthen its access to the sea. In 2018, the Ministry of Defense was tasked with investigating the possibility of establishing a naval force, with the first batch of navy recruits graduating on 27 June 2023. Prior to Abiy coming to power, the previous Ethiopian government showed little interest in rebuilding a naval base and a marine force — which were terminated after Eritrean independence forced Ethiopia into its current landlocked status. According to Abiy, building a naval force is part of an effort to equip the “army with fourth-generation warfare skills” that would defend the country and Africa from non-physical threats like cyber attacks and geopolitical pressure.9Fana Television, ‘Prime Minister Dr. Abiy Ahmed’s conversation with the leaders of the defense army part one,’ 11 June 2018; Fana Television, ‘Prime Minister Dr. Abiy Ahmed’s conversation with the leaders of the defense army part two,’ 11 June 2018

The Ethiopian government also argues that direct access to the sea is essential to meet the needs of a growing population.10Addis Standard, ‘News: Ethiopia’s quest to access sea not a matter of “luxury but of survival”, premier’s security advisor briefs military attachés, reps of international partners,’ 19 January 2024 While the Somaliland government has stated that the recent MoU only applies to the prospective naval base, Ethiopia has sought to use the Berbera port to protect its commercial interests.11X @MadaxtooyadaJSL, 25 January 2024 In 2016, Somaliland and the Dubai-based DP World signed an agreement to develop and operate the Port of Berbera. The Somali government initially rejected this deal, accusing a breach of its sovereignty, but ultimately gave a green light after negotiations with the Somaliland president. However, after Ethiopia signed a deal with DP World in March 2018 to acquire 18% of the Berbera port project, Mogadishu opposed the agreement as the Somalia parliament voted to nullify DP World’s agreement with Somaliland.12Africa Confidential, ‘Washington eyes a base at Berbera,’ 12 April 2022; Richard Wachman, ‘Somaliland backs Dubai’s DP World over Berbera Port,’ Arab News, 19 March 2018; Al Jazeera, ‘Ports war: Somalia bans Dubai ports operator,’ 15 March 2018 The economic crisis caused by the northern Ethiopia conflict and the COVID-19 pandemic prevented the deal from being finalized. However, there are signs that Ethiopia and DP World may revive the agreement, as representatives of the parties expressed their interest in developing Berbera port together in mid-January.13Addis Standard, ‘News: Ethiopia welcomes DP World’s desire to jointly enhance Berbera Port, will negotiate terms of cooperation,’ 25 January 2024

The Interplay between Somaliland’s Quest for Recognition and Somalia’s Aspiration for Unity

The Somaliland government aspires to achieve international recognition. A de facto independent state since 1991, Somaliland has unsuccessfully sought to establish diplomatic relations for over three decades. Its independence claims rest on a peaceful trajectory that is at odds with that of Somalia, which is engulfed in a decades-long conflict with al-Shabaab. By contrast, Somaliland held a constitutional referendum in 2001, started a democratization process culminating in two peaceful transitions of power, and boasts a largely peaceful political system. Thus, it is no surprise that the current Somaliland government wants to link negotiations for sea access with international recognition.

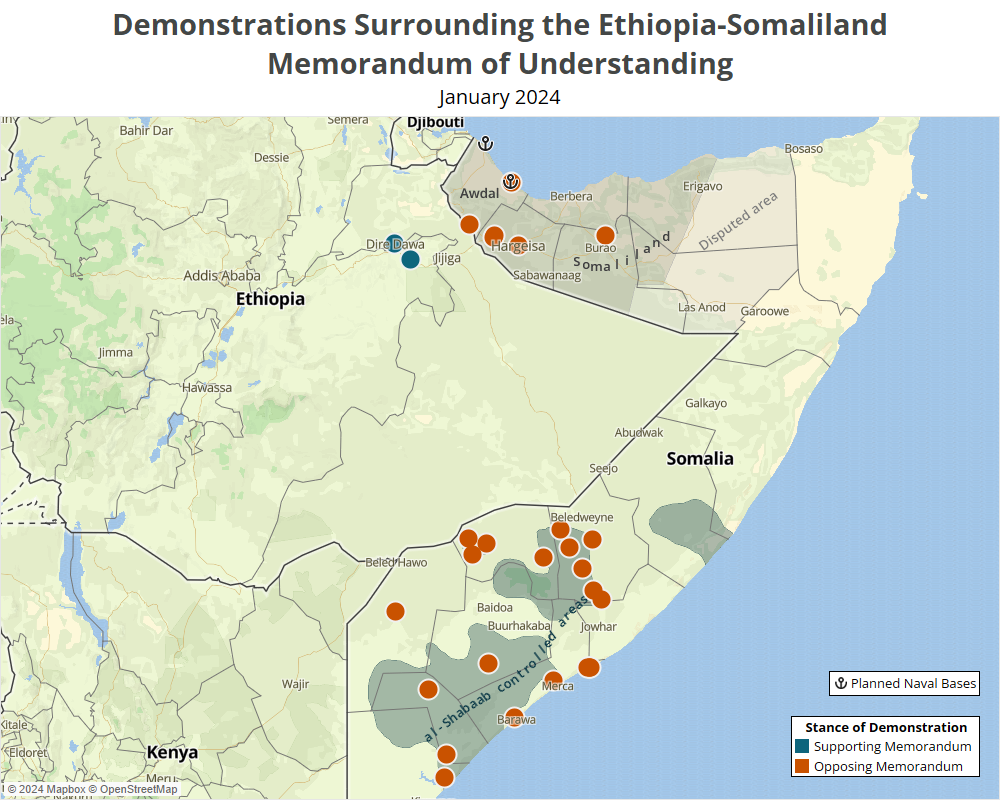

While most Somalilanders welcomed the MoU, not everyone is behind it. The Somaliland government decided to exclude clan leaders from the decision over the MoU with Ethiopia, instead opting for direct negotiations with the Ethiopian government. Demonstrations against the MoU soon broke out in various locations across Somaliland, including the Issa clan-dominated Awdal region. The Issa clan accused the government of President Muse Bihi of selling Issa’s land in exchange for diplomatic recognition and threatened to go to war against the government unless Somaliland withdrew from the MoU. Somaliland’s defense minister — who hails from Awdal region — resigned in protest of the MoU.14Omar Faruk, ‘Somaliland’s defense minister resigns over deal to give Ethiopia access to the region’s coastline,’ AP News, 8 January 2024 One of the major opposition parties in Somaliland also criticized the MoU, arguing that the government had no public mandate to sign the agreement and that Ethiopia’s recognition would not help Somaliland gain independence.15Hiiraan, ‘Somaliland opposition party criticizes port deal between Ethiopia and Somaliland,’ 9 January 2024

The protests were not limited to Somaliland alone. ACLED records at least 33 demonstrations against the MoU in Somalia (see map below). Most of these demonstrations were held in areas controlled by al-Shabaab, which is seizing this opportunity to recruit new members, calling on Somali people to defend and protect their country.16 Interview with an al-Shabaab clan-based elders in Jilib and Bu’aale conducted by ACLED Somalia researcher on 9 January 2024; Caleb Weiss, ‘Shabaab says it rejects Red Sea access deal between Ethiopia and Somaliland,’ Foundation for Defense of Democracies, Long War Journal, 2 January 2024 Over the past two years, al-Shabaab has been increasingly engaged in violent encounters with Ethiopian forces in Somalia or in events along the Ethiopia-Somali border (for more details on the incidents involving al-Shabaab in Ethiopia, see EPO Weekly: 16-22 July 2022, EPO Weekly: 23-29 July 2022, and EPO Weekly: 6-12 August 2022).17China Global Television Network (CGTN), ‘462 al-Shabaab fighters killed in failed attack: Ethiopia’s military,’ 21 September 2023

In 2023, Somaliland experienced increasing unrest. The Somaliland government has been fighting with the militias of Sool, Sanaag, and Ceyn (SSC), which mobilized on a platform to reunite with Somalia. These militias hail predominantly from the local Dhulbahante clan, which has long favored rejoining Somalia over being part of an independent Somaliland state. The recent round of fighting between Somaliland forces and SSC militias broke out in early 2023 after government security forces killed over a dozen demonstrators who were protesting against the assassination of an opposition party member in late December 2022. On 5 January 2023, Somaliland forces withdrew from the capital of Sool region, Laascaanood, ceding control of the regional capital to the Dhulbahante clan and SSC militias, which in turn formed a separate administration known as SSC-Khatumo. In October 2023, the Somalia federal government recognized the formation of the transitional SSC-Khatumo administration, a breakaway authority established by Dhulbahante clan elders with the aim of being recognized as one of the states of Somalia.18The Somali Digest, ‘Somali government makes a strategic move by recognizing SSC-Khaatumo,’ 19 October 2023

Somaliland authorities realize they cannot afford to nurture another conflict with the Issa clan over the contested MoU, endangering domestic stability and upsetting clan relations. Over the past decade, several attempts have been made to bring Somalia and Somaliland together to reach an agreement to unify all territories under the Somali federal government. As recently as 28 December 2023, the Somaliland government and the Somalia government met in Djibouti and agreed to resume peace talks and discuss forming a single Somali government.19Garowe Online, ‘Djibouti revives Somalia Govt’s talks with Somaliland,’ 28 December 2023 However, this was cut short after the news of the MoU broke at the beginning of the new year. The Somali government rejected the MoU and accused Ethiopia of violating its sovereignty and the territorial integrity of Somalia.20Harun Maruf, ‘Somalia rejects Ethiopia sea access deal with Somaliland,’ Voice of America, 2 January 2024

The Geopolitical Significance of the Red Sea

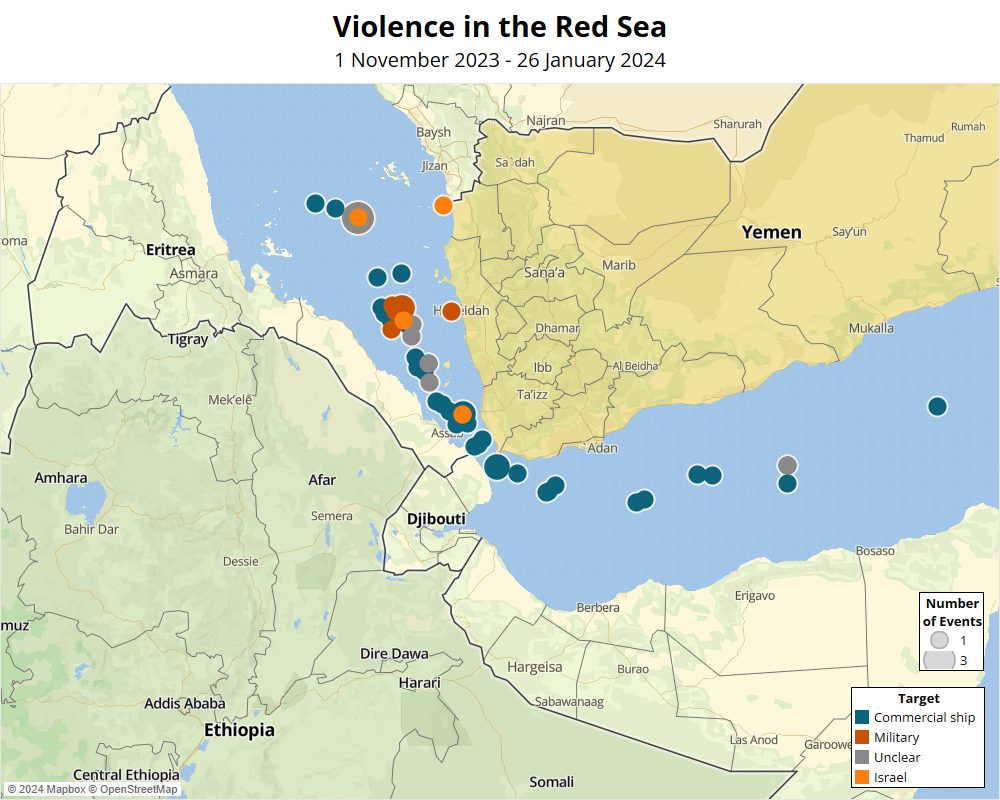

In 2023, the Red Sea once again reclaimed its geopolitical centrality. Stretched between two choke points on the Suez Canal and the Bab al-Mandab strait, the Red Sea has long been one of the world’s key trade routes. Approximately 15% of global sea trade transits through the Red Sea, serving as the shortest route for grains, natural gas, and oil shipments between Asia and Europe.21Finacial Times, ‘Red Sea crisis pushes up delivery times for European manufacturers,’ 1 February 2024 The war in Yemen has brought back instability to the Red Sea, with dozens of violent incidents reported since 2015. Yet, following Israel’s invasion of Gaza in October 2023, Yemen’s Houthis have launched dozens of attacks against the Red Sea shipping lanes, targeting Israel-linked ships (see map below).

Eight countries — Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Sudan, Eritrea, and Djibouti — border the Red Sea, while several others have naval bases on the Red Sea shores. Djibouti hosts most foreign naval bases, housing troops from the United States, Japan, France, China, Italy, Germany, Spain, and India.22Andreu Sola-Martin, ‘Ports, military bases and treaties: Who’s who in the Red Sea,’ The Africa Report, 13 November 2020 Since 2017, Russian warships have been using Port Sudan’s naval base while exploring options to build a naval base in one of the littoral countries.23Garowe Online, ‘UAE cancels constructions of military base in Somaliland,’ 4 March 2020 Western countries see Russia’s and China’s involvement in the region as threatening their strategic interests. Turkey also has a military base in Somalia. Saudi Arabia, which possesses the longest coastline on the Red Sea, and the United Arab Emirates instead see Iran, Turkey, and Qatar’s growing presence in the region as a threat to their security and commercial interests.24David H. Shinn, ‘The Red Sea: A magnet for outside powers vying for its control,’ The Africa report, 27 November 2020

The Horn of Africa’s strategic position has attracted the interest of regional and international powers. Regional turbulence is reflected in the Horn, with reports of foreign troops deployed in the region and multinationals deepening commercial interests.25Zach Vertin, ‘Red Sea geopolitics: Six plotlines to watch,’ Brookings, 15 December 2019 Ethiopia’s plans to build a naval base in Somaliland tap into a complex web of regional alliances. Until now, the UAE — a close partner to Ethiopia and Somaliland and an influential power in the Red Sea — has been silent on this issue. Ethiopia and the UAE continue to maintain close economic ties, as illustrated by the UAE’s announcement of investing $2.4 billion in Ethiopia.26Addis Standard, ‘UAE investing $2.4 billion in Ethiopia,’ 5 February 2024 Though the Somali government initially rejected negotiations with Ethiopia over sea access in October 2023 and early January 2024, Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud indicated on 23 January “that the federal government was ready to negotiate a deal with Addis Ababa.”27Al-Jazeera, ‘‘Don’t do it’: Somali president warns Ethiopia over Somaliland port deal,’ 23 January 2024

Somalia is instead attempting to enlist support from Egypt and Eritrea, which recently had disputes with Ethiopia over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on the Nile and the northern Ethiopia conflict, respectively. The relationship between Egypt and Ethiopia has soured, with the former supporting Somalia in claiming that Ethiopia represents “a source of instability in the region.”28Reuters, ‘President El-Sissi Says Egypt Will Not Allow Any Threat to Somalia or Its Security,’ Voice of America, 21 January 2024 Eritrea, which supported the Ethiopian government during the northern Ethiopia conflict against the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), is instead reported to have concerns over the peace agreement signed between the Ethiopian government and the TPLF in November 2022. The agreement allows the TPLF to remain the regional government of Tigray, a provision that is considered unacceptable by the Eritrean government, which considers the TPLF an enemy.29Michael Woldemariam, ‘Taking Ethiopia-Eritrea Tensions Seriously,’ United State Institute of Peace, 15 December 2023

Whether the MoU will lead to building a naval base, granting Somaliland international recognition, or escalating regional tensions is largely conditioned on how these countries negotiate their mutual aspirations. If Ethiopia and Somaliland are unable to rally any support but still want to go ahead with the deal, they may be drawn into a larger regional confrontation with their neighbors. The parties may avoid conflict in two scenarios: in the first, if Somalia’s diplomatic campaign succeeds, Ethiopia and Somaliland may be pressured to scrap plans for the naval base and instead continue deepening commercial and economic ties. In the second, Ethiopia could gain sea access, either on the condition that it drop official recognition of Somaliland, or if Mogadishu accepts the deal, as it did in 2016 with the DP World development of Berbera, in exchange for investment on its territory. Due to the region’s global significance, regional and international stakeholders will continue to watch this new row in the Horn of Africa.