Last updated: 08/08/2024

Oromia is the largest region in Ethiopia. Stretching across the country from east to west, the region represents 34% of Ethiopia’s territory and is home to over 37 million people.1Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Central Statistical Agency, ‘Population Projection of Ethiopia for All Regions At Wereda Level from 2014 – 2017,’ August 2013 It is divided into 20 administrative zones, 30 town administrations, and 287 rural and 46 town woredas. According to the last official census conducted in 2007, more than 65 ethnic groups and peoples from neighboring countries live in Oromia region, including many in western Oromia or in areas surrounding the capital, Addis Ababa.2Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Population Census Commission, ‘Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census,’ December 2008 The majority of the region is inhabited by the Oromo ethnic group, followed by the Amhara, Gurage, and Gedeo ethnic groups.

Oromia region has been the site of anti-government protests and insurgency for many years. Mass mobilization swept through the region between 2014 and 2018, driven by opposition to the rule of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic government. This movement was instrumental in bringing current Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed to power in April 2018. During the pre-Abiy years, the Qeerroo youth movement in Oromia was able to enforce economic strikes, hijack government-sponsored events, and disrupt government activities on a regular basis – despite lacking set organizational structures. These activities were undertaken in the face of heavy repression by state forces, with the excessive use of state violence against protesters seeming to drive the protest sentiment.

‘Qeerroo’ is a broad term for a social movement that is not coordinated vertically, regionally, or nationally, but manifests as a local movement. These are predominantly — but not exclusively — young men who appoint one or more local coordinators (though not strictly ‘leaders’). The movement’s participants have generally been motivated by a sense of Oromo grievance about exclusions and marginalization, local politics and faultlines, and engagement in redefining ‘Oromoness.’ Yet, this latter concept varies according to sub-regional differences, particularly Shewa, Bale, Harar, and Wollega Oromos, who have distinct hierarchical cultural and historical interpretations and understandings of ‘Oromoness.’ During the 2014-18 demonstrations, these groups coalesced into a region-wide but autonomous movement, still without a leader. As a social movement with localized expressions, it is not an organization that can be coordinated nationally.

Political dynamics in Oromia region

At the outset of Ethiopia’s political change through Abiy Ahmed, a number of Oromo politicians and activists living abroad returned to the country and began to engage in politics. Among them were diaspora actors like Jawar Mohammed — self-proclaimed leader of the Qeerroo — who returned from Minnesota, United States, and joined the Oromo Federalist Congress (OFC) party. OFC leaders had been jailed over their roles in violent riots that occurred in June 2020, and dropped out of the 2021 general election. Some of the leaders, including Jawar Mohammed and Bekele Gerba, were released on 7 January 2022 following an amnesty by the federal government on Ethiopia’s Christmas day.3Dawit Endeshaw, ‘Ethiopia frees opposition leaders from prison, announces political dialogue,’ Reuters, 8 January 2022

The return of political actors also included the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), which fought an insurgency with the goal of self-determination for the Oromo people from its base in Eritrea for nearly three decades. The OLF’s political “struggle” has since been marred with a leadership crisis, and it dropped out of the 2021 election, citing the arrest of members and the closing of political offices.4Siyanne Mekonnen, ‘News Analysis: OLF officially out from upcoming election, continues call for release of its jailed leadership, members,’ 10 March 2021 Importantly, some OLF commanders viewed the developments with distrust and as transitional theatrics, and opted to continue insurgent activity across Oromia. This splinter group, the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA), is identified by the government and non-Oromos as the OLF-Shane. The group was designated as a ‘terrorist organization’ by the House of Peoples’ Representatives on 6 May 2021. According to the federal government, the decision would allow it to prevent and suppress the OLA/OLF-Shane’s actions in accordance with the law.5Office of the Prime Minister-Ethiopia, ‘Council of Ministers passed a proposal on categorizing “Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF)” and “Shane” as Terrorist Organisations,’ 1 May 2021

During the sixth general election in 2021, major opposition parties OLF and OFC staged a boycott and called for a national dialogue, the establishment of a transitional government, and new elections to be held within one year.6Oromo Federalist Congress-OFC, ‘An election that is not fair and not inclusive cannot deliver democracy. A statement from The Oromo Federalist Congress on the Ethiopian ‘Elections’,’ 23 June 2021 As a result, the ruling Prosperity Party (PP) was uncontested in the election and won all of the Oromia regional council seats as well as 167 seats in the House of Peoples’ Representatives.7National Electoral Board of Ethiopia (NEBE), ‘A summary of the seats won by parties in the constituencies of the House of Representatives and the Regional Council elections on June 14, 2013,’ 12 July 2021 The Oromia region has in total 178 designated seats in the House of Peoples’ Representatives. On 21 June 2021, the election was held for 170 seats; however, voting was not held in seven electoral constituencies due to security reasons. These constituencies included the Begi and Monday Market in West Wollega zone, Ayana and Galilee in East Wollega zone, and Alibbo, Gida, and Kombolcha in Horo Guduru zone.8NEBE, ‘Information from the National Electoral Board,’ 1 June 2021 On election day, the voting process was peaceful in most parts of the region. However, election-related violence was recorded in areas where the OLA/OLF-Shane operates (for more, see EPO Weekly: 19-25 June 2021).

By tracking all reported demonstration events in Oromia, the EPO has identified four distinct phases that have shaped the region’s political environment since 2018.

- A short phase of demonstrations and riots that occurred directly after Abiy took power in 2018, mostly in areas where grievances were extremely high while political space varied depending on location. Examples were the Somali protests against the former Somali regional president, Abdi ‘Illey,’ or the Burayu riots sparked by the return of OLF fighters to the city. During this phase, elite and public grievances were generally not aligned, and demonstrations quickly died out.

- A phase of ethnic agitation. Protest and riot events recorded throughout the country during this phase all reflected similar ethnicity-related themes — crowds agitating for greater ethnic autonomy or protection in reaction to attacks based on identity. These protests and riots were held with little intervention at first. However, as time went on, the government became increasingly intolerant of the protests, resulting in heavy levels of violence. During this phase, major riots occurred on university campuses across the region and culminated in two extremely violent events in 2019 and 2020. First, in late October 2019, rumored attempts to harm opposition activist Jawar Mohammed sparked days of violent protests across the region, resulting in dozens of fatalities. Second, the killing of popular Oromo musician Hachalu Hundessa in the summer of 2020 in Addis Ababa prompted waves of youth to mobilize for protests and riots. During both rounds of violence, rioters blocked roads, destroyed infrastructure, and attacked ethnic minorities throughout Oromia region. According to local sources in East Hararge, the federal police’s response to the crises was delayed. In some cases, local Qeerroo militias were reportedly mobilized to provide security and even make demands over resource allotment and utilization.9Interview conducted in East Hararge zone by ACLED researcher, February 2021 OFC and OLF officials were arrested at the end of this phase, accused of inciting the riots that led to high numbers of fatalities.

- A phase of intense government repression, where protesters were less willing to mobilize and government forces exacted heavy punishments against protesters, making mobilization rare. Attempts by protesters to demonstrate against the arrest of Oromo politicians (dubbed the Yellow Movement) in 2021 were quickly and violently dispersed by security forces.

- A phase of intensifying insurgency, marked by high levels of violence against civilians by both government and anti-government forces. Very few protests were reported during this phase, which also coincided with elevated levels of political violence in the form of battles, especially in the west of the region.

Political violence dynamics in Oromia region

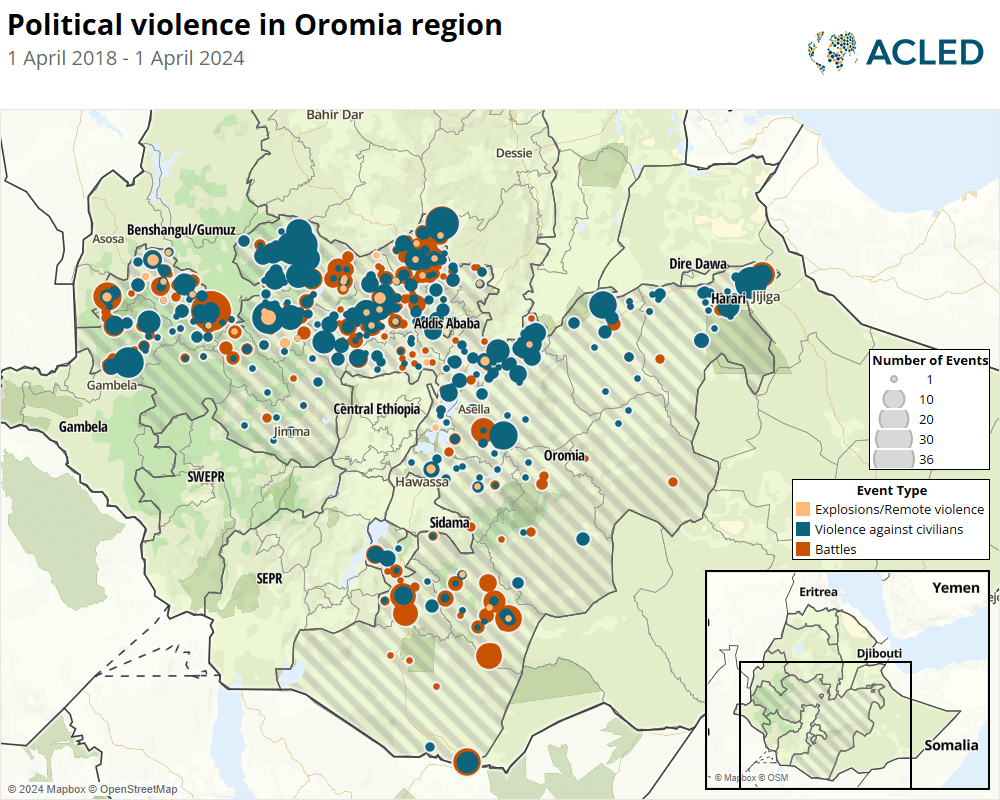

Two main violence types determine the dynamics of political violence in the region: battles between government troops and the OLA/OLF-Shane in different parts of the region, and violence against civilians perpetrated by government forces, the OLA/OLF-Shane, and Amhara ethnic militias (for more details on violence against civilians in Oromia, see the EPO Monthly: June 2022). Violence in Oromia is generally most concentrated in the western and northern parts of the region, where the OLA/OLF-Shane has the most influence (see map below). However, there are points of conflict in nearly every part of the Oromia region (for more, see the EPO’s Western Oromia Conflict and Borena Zone Conflict profiles).

In February 2022, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed admitted that the federal government was struggling to control the OLA/OLF-Shane due to the group’s high level of public support in Oromia. Abiy also admitted that “a military strategy alone would not work” due to “[Oromo] people hiding the armed fighters.”10Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation, ‘The 3rd Emergency Meeting of the House of Representatives – Chapter Two,’ 22 February 2022 Moreover, the government admitted that the OLA/OLF-Shane had regained control of 1,739 kebeles in the region, while the government only managed to regain control of 1,255 kebeles.11Office of the Prime Minister-Ethiopia, ‘In consultation on current national security and security issues, a statement from the National Security Council,’ 8 August 2022 Though the government announced that operations against the OLA/OLF-Shane had been successful, the group continues to operate in Oromia and has regained control of various territories. In November 2022, the group was in control of 11 of the 21 woredas in East Wollega zone, and also managed to enter one of the biggest administration centers in the region, Nekemte, attacking government forces and freeing prisoners.12Emmanual Yilkal, ‘It has been reported that district leaders and residents in West Wolega are fleeing due to attacks and threats by “ONG Shene”, Ethiopian Reporter, 6 November 2022

Meanwhile, since September 2022, airstrikes targeting the OLA/OLF-Shane have increased in the region. As the armed group is embedded with civilians, these airstrikes also affect civilians, resulting in fatalities. Such airstrikes were recorded in East Shewa, West Shewa, West Wollega, and East Wollega zones.

In 2023, the federal government and OLF-Shane representatives met twice, first in April/May 2023, and again in November 2023, for peace talks. However, the talks were not successful and violence increased at the conclusion of the talks on both occasions. The government attributed the failure to the “intransigence” of the OLA/OLF-Shane leadership.13Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Government Communication Service, ‘The two-round talks with Shane concluded without results,’ 21 November 2023 OLA/OLF-Shane commanders indicated that they had rejected “offers of power” and blamed government representatives for “failing to address the underlying issues affecting the country’s politics and security.”14Twitter @OdaaTarbiiWBO, 24 November 2023 Senior politicians, including the former state minister for peace, human rights organizations, and influential diaspora organizations, have expressed their disappointment in the talks’ unsuccessful outcome, with some pointing to government military actions carried out during the talks.15Addis Standard, ‘News: Global Oromo Interfaith Council urges resumption of peace talks in Ethiopia amidst stalled negotiations,’ 24 November 2023; Taye Dendea Aredo, Facebook Statement, 21 November 2023