Last updated: 20/08/2024

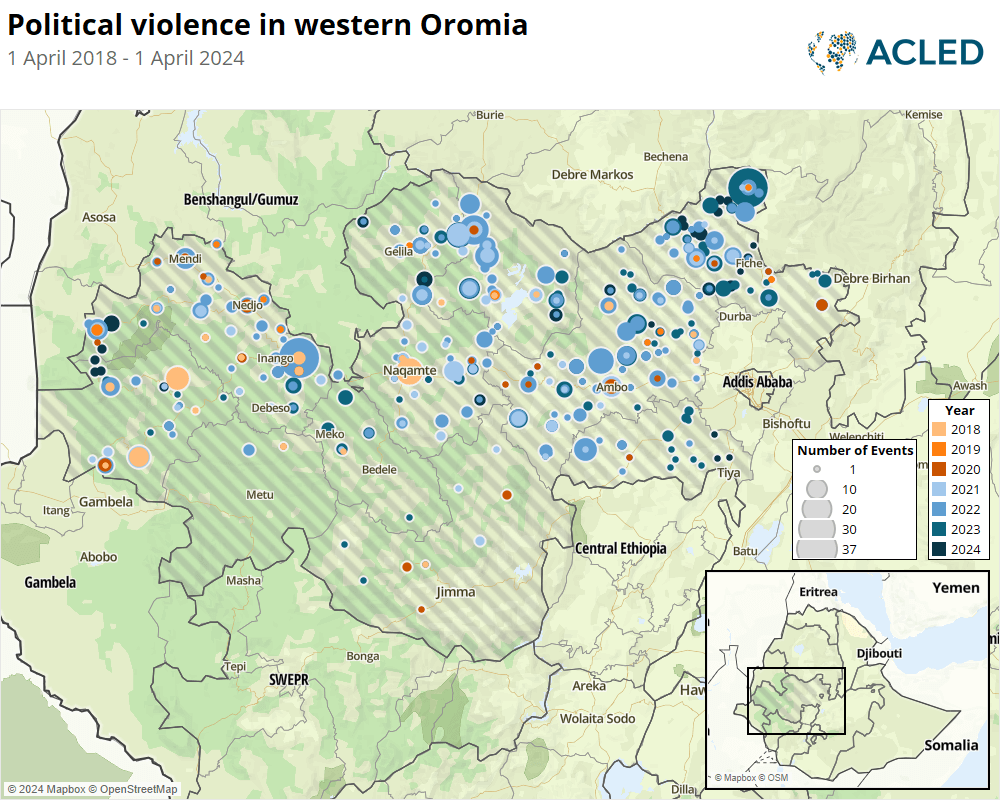

Western Oromia is the site of a long-sustained insurgency that has grown significantly more serious since Abiy Ahmed came to power as prime minister of Ethiopia in 2018 (see map below). Compounded by ethnic violence and communal clashes, political violence in the area reached an all-time high in November 2022 (for more, see the EPO Monthly: November 2022). Large swaths of territory within western Oromia are outside the federal government’s control, and thousands of people have been displaced by ongoing violence.

The Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) — referred to by the government as the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF)-Shane — is an armed insurgent group that splintered from the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) in 2019. Distrustful of Abiy’s promised political reforms, commanders of the OLF’s armed operations wing in Ethiopia refused to disarm with the rest of the OLF’s leadership in 2018. These commanders officially split from the OLF’s political wing in 2019 and have since maintained an anti-government insurgency in the peripheral areas of western Oromia. Throughout 2020, 2021, and 2022, the group grew exponentially and controlled large swaths of territory in rural and semi-rural locations throughout the area.

Beyond controlling territory, their activities consist of hit-and-run attacks against police and military forces.1Zecharias Zelalem, ‘Failed politics and deception: Behind the crisis in western and southern Oromia’, Addis Standard, 20 March 2022; BBC Amharic, ‘The residents of West Oromia said that the movement of transport has been disrupted,’ 14 August 2021 In return, government forces have jailed suspected OLA/OLF-Shane supporters and killed suspected members of the OLA/OLF-Shane militias.2Fana Broadcasting, ‘Police said that action was taken against 265 members of ONG Shene in West Welega Zone in two months,’ 11 January 2021; Fana Broadcasting,‘Six individuals who were allegedly arrested while carrying out a mission in coordination with the TPLF and the NGO Shene appeared in court,’ 22 March 2021; Fana Broadcasting, ‘The Oromia Police stated that action was taken against 21 members of ONL Shene,’ 20 March 2021 These crackdowns have led to severe pressure on local populations in Oromia.

While information in this area is extremely difficult to access, reports of continued violence, displacement, and insecurity suggest that the issue has developed far beyond the capacity of a local law enforcement operation and that increased military efforts will be required to gain full control over the area and root out the insurgency led by OLA/OLF-Shane.

OLA/OLF-Shane has succeeded in western Oromia but has struggled to find footing in other areas of the region for several reasons, including the presence of territorial disputes in western Oromia that have affected local populations for decades. In areas of western Oromia, particularly in East, West, and Horo Guduru Wollega zones, ethnic Amharas that settled in villages south of the Amhara-Oromo regional border during the 1970s and 1980s have occasionally clashed with the Oromo inhabitants over land and resources.3Zelalem Teferra, ‘Shifting trajectories of inter-ethnic relations in Western Ethiopia: a case study from Gidda and Kiremu districts in East Wollega,’ Journal of Eastern African Studies, 20 September 2017 These clashes have worsened significantly since Abiy took power — likely due to the northern conflict pulling security resources away from the area. Limited but regular clashes between Oromo and Amhara ethnic militias occur, often accompanied by mass civilian displacement.4VOA Amharic, ‘Petition of evacuees in South Wolo Zone. Displaced people from different areas of Oromia region have been displaced in South Wolo Zone, Kalu District, Harbu Kete in Amhara Region,’ 23 November 2022

Like all ethno-national movements in Ethiopia, Oromo ethno-nationalism is highly connected to language and land. In these areas of regular conflict centered around contested territory, the OLA/OLF-Shane has found an opportunity to champion itself as the chief defender against territorial encroachments. This positioning, however, has placed it in direct conflict with local Amhara communities, and the group has been blamed for a series of massacres of local civilians, which they have denied.

One of the highest fatality incidents illustrating these dynamics occurred in August 2021. According to the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC), on 18 August 2021, gunmen associated with the OLA/OLF-Shane attacked residents in Gida Kiramu district of East Wollega, reportedly killing 150 people “based on their ethnic identity.”5Ethiopian Human Rights Commission, ‘East Wolega: The local security force should be strengthened to ensure the safety of the residents,’ 26 August 2021 The commission went on to describe 60 other killings based on “ethnic retaliation” that happened in the days following the initial massacre.6Ethiopian Human Rights Commission, ‘East Wolega: The local security force should be strengthened to ensure the safety of the residents,’ 26 August 2021 The statement was immediately rejected in a communiqué by an OLA spokesperson. The OLA instead insisted that the deaths occurred in the midst of heavy fighting between OLF-Shane fighters and an Amhara militia that had crossed the border into the region and displaced Oromo farmers from contested territory.7OLA Press Release, ‘Press release regarding the situation in East Walaga,’ 25 August 2021 The communiqué disputed the charge that the OLA attacked civilians. The Oromo Liberation Front party faction led by Dawud Ibsa likewise condemned the EHRC statement, accusing the commission of bias and unprofessionalism in regard to investigating the incident.8Oromo Liberation Front, ‘OLF is Troubled to Believe the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission Reports,’ 27 August 2021 Violence continually reemerges in these areas, with the latest incidents occurring in November and December 2022 (for more, see the EPO Monthly: December 2022).

Federal interventions into West and Kellem Wollega zones include risks to the capacity of the state forces to adequately control the area, as well as an increase in violent behavior throughout Oromia region. There are frequent examples of excessive force: an investigation by the EHRC found that an 11-year-old boy, a 12-year-old boy, and a 14-year-old girl had been held in detention since mid-December 2020 for being suspected members of OLA/OLF-Shane.9Ethiopia Human Rights Commission,‘ Gambella Region: Protection of Human rights Requires Urgent Attention,’ 25 January 2021 In May of 2021, a 17-year-old boy was shot and killed by Oromia special forces in a public square in Dembi Dolo.10Addis Standard, ‘Days after Rights Commission report of massive crackdown on civilians, security forces in Oromia execute a young man in public view; Zonal, City admin officials justify the act,’ 12 May 2021 Complete telecommunications blackouts as part of security operations are common and hinder the reporting of incidents of violence against civilians.11Ermias Tasfaye, ‘Amid blackout, western Oromia plunges deeper into chaos and confusion,’ Ethiopia Insight, 14 February 2020

OLA/OLF-Shane’s success lies in its popularity with and dependency on the local populations, making high civilian casualties likely during operations. Operations against the OLA/OLF-Shane are risky in that civilian casualties, destroyed housing, or assault on innocent civilians could radicalize those who support the opposition but do not currently side with the OLA/OLF-Shane movement. Unless the government and OLA/OLF-Shane forces enter a period of sincere negotiations, the conflict in Oromia will inevitably continue. Given the current circumstances, the conditions for civilians, especially those living in zones of territorial conflict in the northwest of Oromia region, will likely continue to worsen.

In April 2023, patterns of violence involving the OLA/OLF-Shane shifted to the east, and the amount of political violence in the western areas of Oromia region lessened. This shift coincided with an effort at peace negotiations between the OLA/OLF-Shane and the government, which ultimately failed. The shift also occurred at the same time as the dissolution of the country’s regional special forces in April 2023. Prior to their dissolution, the Oromia regional special forces were the most active government actor in west Oromia. The Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) has since taken the place of the Oromia regional special forces. Violence levels in western Oromia have since remained steady, at reduced levels relative to the spikes in July and November 2022.