November 2022 marks two years since the conflict in northern Ethiopia began. After Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed came to power on 2 April 2018, the relationship between the federal government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) began to deteriorate due to one major issue – Ethiopia’s governance system. From 1991 to 2018, the TPLF dominated the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) political coalition and shaped Ethiopia’s governance guided by revolutionary democratic ideals — also dubbed Abyotawi democracy.1Abyotawi democracy is a concept adopted from Marxist-Leninist-Maoist thought, which holds that elites must lead the masses to revolution and guide the democratic process of the country (Bach, 2011, p. 643). It “defends collective rights through the notion of Nations, Nationalities and Peoples” (Bach, 2011, p. 644). When Abiy Ahmed came to power, he shifted away from Abyotawi democracy and introduced a new concept called “Medemer,” which supports a pan-Ethiopian democracy, “tailor-made” for Ethiopian culture, consciousness, and thinking (Abiy Ahmed, 21 October 2019). The main objectives of Medemer are to build on Ethiopia’s rich heritage, rectify past mistakes, and encourage working together for the country’s future. Medemer has three pillars: national unity, the honor of citizens, and prosperity.

Political differences came to a head almost immediately following Abiy Ahmed’s ascension to power. The TPLF opposed and refused to join the new ruling party, the Prosperity Party, established by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. Instead, Tigrayan members of the federal government abandoned their posts and headed to Tigray region, and shortly after, held a regional election in defiance of the federal government in September 2020 (Al Jazeera, 9 June 2020; Reuters, 8 September 2020). Political grievances were expressed violently for the first time on 3 November 2020, when the Tigray regional special forces and militias, under the direction of the TPLF, attacked the northern command of the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) in Tigray region. Since then, the conflict passed through various stages until the day before its second year, 2 November 2022, when the federal government and the TPLF signed the Agreement for Lasting Peace through a Permanent Cessation of Hostilities (VOA Amharic, 2 November 2022).

This special report analyzes various elements of the recently signed peace agreement and examines the presence of both third-party guarantees and effective institutions. This framework is based on the work of scholars who theorize that for an agreement to establish sustainable peace, those two elements are important. Third-party guarantors are responsible for monitoring the implementation of a peace agreement and using different techniques to halt civil wars and establish sustainable peace. Effective institutions make the government abide by the terms of a peace agreement, which in turn minimizes the urge for rebel groups to retain militias to make the government accountable (Walter, 1997; Walter, 2002; Walter, 2015; Fortna, 2003; Doyle & Sambanis, 2006).

While the latest round of fighting indicated that the TPLF had been weakened – most likely critically, and unable to resume warfare in any major form – the presence of contested land compounded by weak institutions and absent third-party guarantees makes the peace agreement unlikely to last in its current form. Although the two conflicting parties agreed that the African Union (AU) would establish a Monitoring and Verification Team consisting of up to 10 experts to oversee the implementation of the agreed terms, the team has not yet been established.

The Time Frame of the Northern Ethiopia Conflict

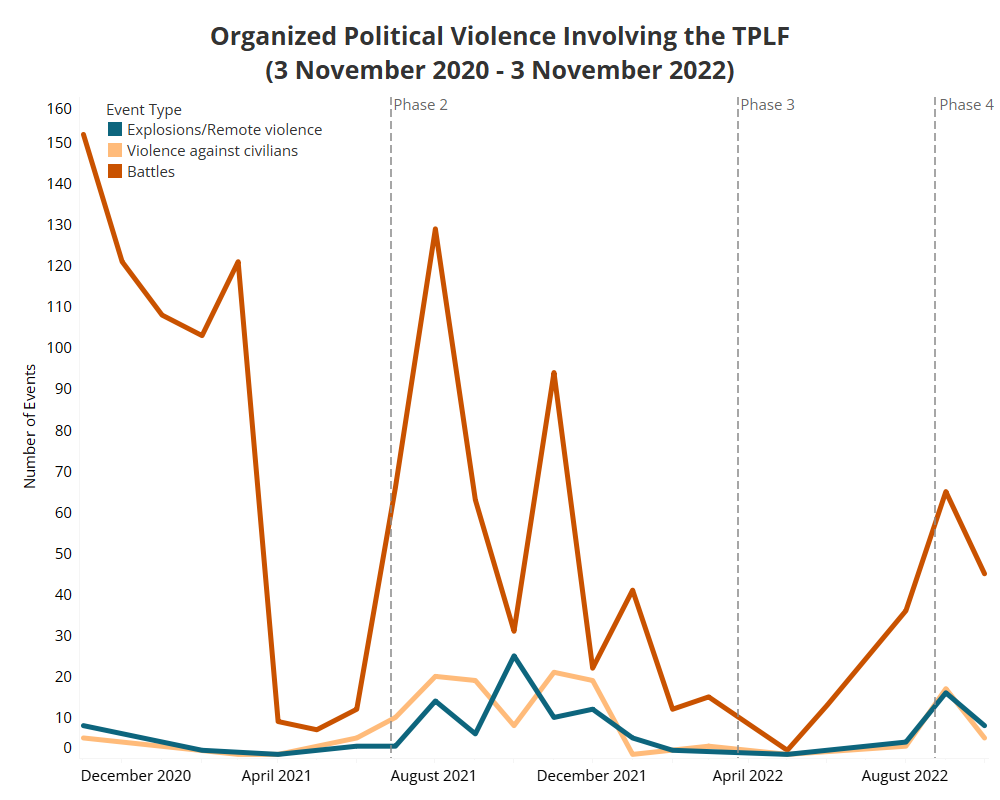

The northern Ethiopia conflict passed through four stages before the Ethiopian government and the TPLF signed the Agreement for Lasting Peace through a Permanent Cessation of Hostilities on 2 November 2022 in Pretoria, South Africa (see graph below). These four stages are:

- First stage: 3 November 2020 to 27 June 2021;

- Second stage: 28 June 2021 to 23 March 2022;

- Third stage: 24 March to 23 August 2022; and

- Fourth stage: 24 August to 2 November 2022.

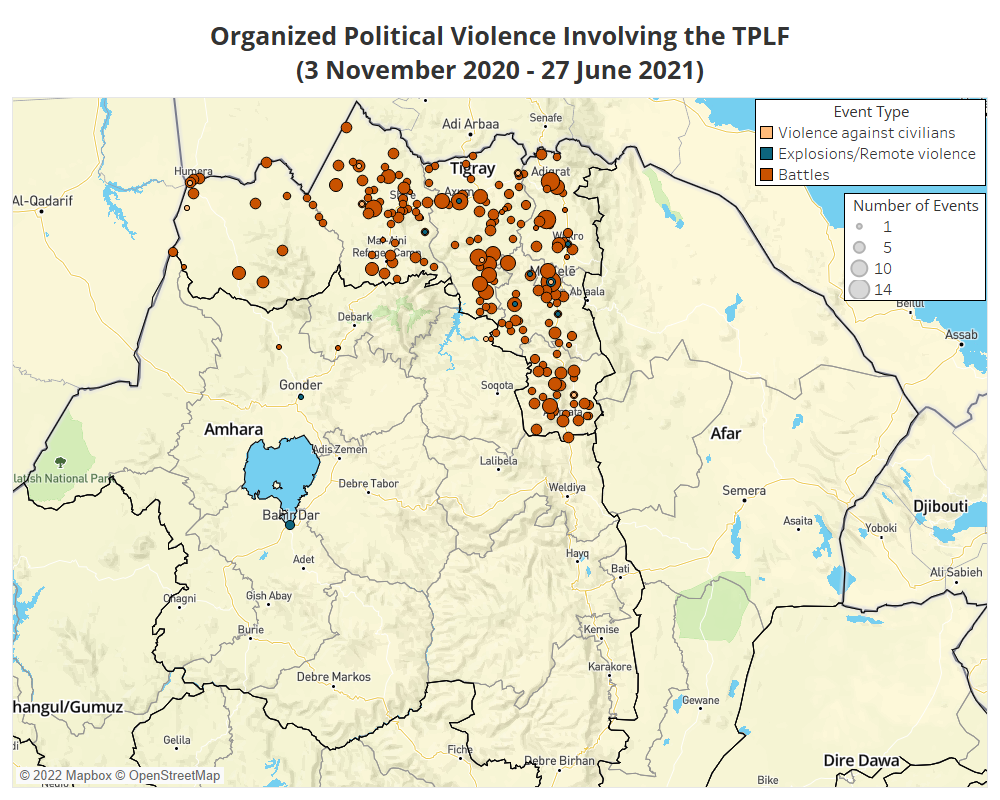

The first stage of the armed conflict erupted in Tigray region after the Tigray regional special forces and militias, under the command of the TPLF, attacked the ENDF’s northern command post. This attack led to four weeks of intense fighting, during which federal forces successfully gained control of all major cities in the region, including the capital city, Mekele. In this period, the Eritrean Defence Forces (EDF) were involved in the war, supporting the federal government (Reuters, 23 March 2021). Activity during the first stage of the conflict was concentrated in Tigray region, though some battle events involving TPLF forces were recorded in Amhara region and Eritrea (see map below).

After government forces regained control of Tigray region in November 2020, TPLF forces switched tactics and began an insurgency. This marked a shift from the more conventional fighting tactics they had used during the first four weeks of the conflict. TPLF forces became increasingly difficult to identify as they integrated with the local population. Ethiopian and Eritrean forces reportedly carried out mass killings of civilians (Ethiopian Human Rights Commission, March 2021), and sexual violence was reported to have been perpetrated by all parties to the conflict (Foreign Policy, 27 April 2021). At the time, there was a perception among the local population that the Ethiopian and Eritrean armies were present in Tigray to punish the region for supporting the TPLF. This led to the successful recruitment of many youths who opposed what was happening to their families and allowed for the formation of a formidable fighting force, the Tigray Defense Forces (TDF) (AP, 14 July 2021; BBC, 1 July 2021). While the TDF’s main manpower and training was based on that of the Tigray regional special forces and militias that were formed by the TPLF prior to the outbreak of the conflict, its incorporation of thousands of Tigrayan youths during this period was significant. Meanwhile, the ENDF incurred heavy losses and Ethiopia’s top officials were crippled by diplomatic pressure – including sanctions – over accusations of civilian targeting and the involvement of Eritrean troops (BBC, 29 June 2021; Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation, 3 July 2021). Frustrated and facing an impending humanitarian and military disaster, the federal government decided to withdraw its forces from the region on 28 June 2021 after announcing a unilateral ceasefire (International Crisis Group, 9 July 2021).

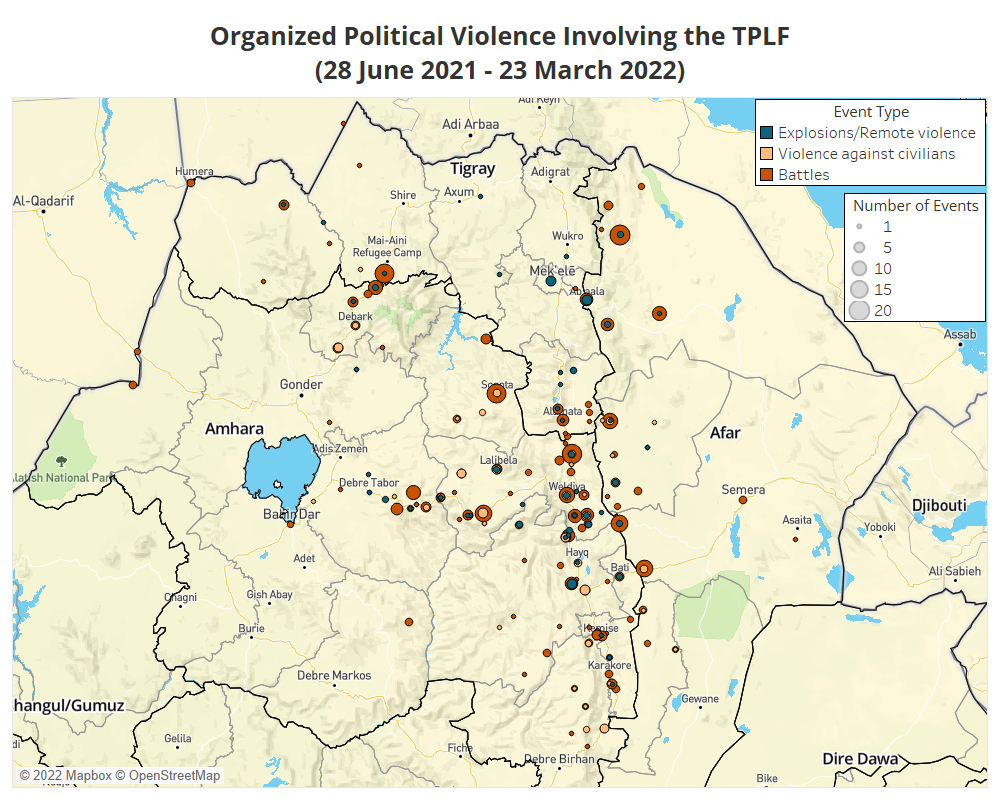

The withdrawal of the ENDF and the government’s announcement of the unilateral ceasefire marked the beginning of the second stage of the armed conflict. The TPLF called the ceasefire a “joke,” and promised to pursue and attack Eritrean forces, the ENDF, and Amhara regional forces unless its seven conditions for a mutual ceasefire in Tigray region were fulfilled (Reuters, 29 June 2021; Twitter @reda_getachew, 4 July 2021). The TPLF’s conditions included the withdrawal of Eritrean soldiers and Amhara regional forces from Tigray region. The TPLF also demanded full access to government services like telecommunications, electricity, banking, and transportation, as well as unlimited humanitarian access to the region (see EPO Weekly: 3-9 July 2021 for more details on these preconditions). In an effort to compel the federal government to accept this list of conditions, TPLF forces began attacking territories within Afar and Amhara regions (see map below). The expansion of the conflict into Afar and Amhara regions prompted regional governments to issue calls for youths to mobilize and combat TPLF forces (BBC Amharic, 26 July 2021; BBC Amharic, 25 July 2021; Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation, 26 July 2021).

However, by the beginning of November 2021, TPLF forces had regained control of Dessie and Kombolcha towns, while the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF)-Shane, which had announced its alliance with the TPLF in August 2021, began to control areas within Oromia special zone in Amhara region. This development sparked widespread concern that TPLF forces would move further south and threaten the capital city, Addis Ababa, and other locations. As a result, the federal government declared a state of emergency on 2 November 2021 (see EPO Weekly: 30 October-5 November 2021 for more details on the state of emergency). Under the state of emergency, thousands of civilians, mostly Tigrayans with suspected links to the TPLF or OLF-Shane, were arrested throughout the country (for more, see EPO Weekly: 6-12 November 2021).

On 24 November 2021, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed announced his decision to lead ENDF forces “from the [war] front” (Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation, 30 November 2021). In December, government forces rapidly began regaining control of most of the areas within Afar and Amhara regions as the ENDF continued to fight with TPLF forces using drones. On 20 December 2021, TPLF leaders announced the withdrawal of their forces back to the borders of Tigray region, while the government announced an end to the first round of military action against the TPLF and indicated it would no longer advance towards Mekele (VOA, 20 December 2021; Twitter @FdreService, 24 December 2021). Nevertheless, fighting continued on the borders of Tigray, Afar, and Amhara regions until the Ethiopian government declared a unilateral ceasefire on 24 March 2022 (Twitter @FdreService, 24 March 2022). The Tigray regional government, led by members of the TPLF, also agreed to a “cessation of hostilities” for humanitarian assistance (Twitter @TigrayEAO, 24 March 2022).

The destruction caused by TPLF forces in Afar and Amhara regions has devastated local infrastructure and disrupted the lives of thousands of people (Amhara Media Corporation, 29 September 2022; The New Humanitarian, 31 March 2022; ENA, 21 April 2022). The conflict forced millions of civilians to flee their homes (Ethiopian Monitor, 7 December 2021) and created a humanitarian crisis in northern Ethiopia. The advance and retreat of the TPLF in 2021 also exposed deep-seated deficiencies within the ENDF and the need for reform.

Weakened by the defection of the Tigrayan leadership, attacks on the northern command, and an antiquated air force, the ENDF performed poorly throughout the conflict in 2020 and 2021 (New York Times, 12 October 2021). However, extensive recruitment, technology updates, and changes in leadership significantly changed the ENDF over the past year (Fana Television, 21 January 2022). From 4 November 2020 to 2 December 2022, airstrikes in Afar, Amhara, and Tigray regions have resulted in 449 reported fatalities in Afar, Amhara, and Tigray regions, and the strikes have played a major role in the conflict against the TPLF. Ethiopia’s Air Force appears to be much more capable today than it was in November 2020. The introduction of new technology, including drones from the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, and Iran, has bolstered its capacity (New York Times, 20 December 2021). In addition to technology updates, the federal government made significant efforts to increase the manpower of the ENDF during this phase through reportedly large-scale recruitment drives (AllAfrica, 26 July 2021). By the third and fourth stages of the armed conflict, these strategies appeared to have paid off, as the ENDF proved to be far superior to its TPLF opponents.

During the third stage of the conflict, no major clashes were reported between the two groups. Though not enough to cover local needs, limited amounts of humanitarian aid were entering Tigray region consistently by airplanes and trucks traveling on the Semera-Abala-Mekele road (UNOCHA, 7 April 2022). At the same time, the international community – especially the United States (US), European Union (EU), and AU – was trying to bring the two parties to the negotiation table. In June 2022, the Ethiopian federal government established a peace committee led by Deputy Prime Minister Demeke Mekonen, representing the government, and insisted that the AU High Representative for the Horn of Africa, Olusegun Obasanjo, lead the peace negotiations (Fana BC, 13 July 2022; VOA, 14 June 2022). However, the TPLF rejected this proposal and instead wanted the US and EU to lead the negotiations (The Africa Report, 22 August 2022; Tigray TV, 18 August 2022; Twitter @TigrayEAO, 14 June 2022). Moreover, the TPLF continued to insist on the fulfillment of its preconditions, especially restoring basic necessities in Tigray and unlimited access to humanitarian aid (France24, 25 August 2022; AllAfrica, 4 July 2021). As a result, in early August 2022, the TPLF sent a letter to the federal government through the US and EU Special Envoys for the Horn of Africa. According to a US and EU joint statement, the letter promised to provide “security guarantees for those who need to work to restore services” (US Embassy in Ethiopia, 2 August 2022). In response, the federal government said there “is no on and off button that is centrally located” to restore these services in Tigray, and detailed the process to restore damaged equipment, including the need for different institutions like Ethio Telecom to be physically present with their offices open and operational in the region (Office of the Prime Minister – Ethiopia, 18 August 2022).

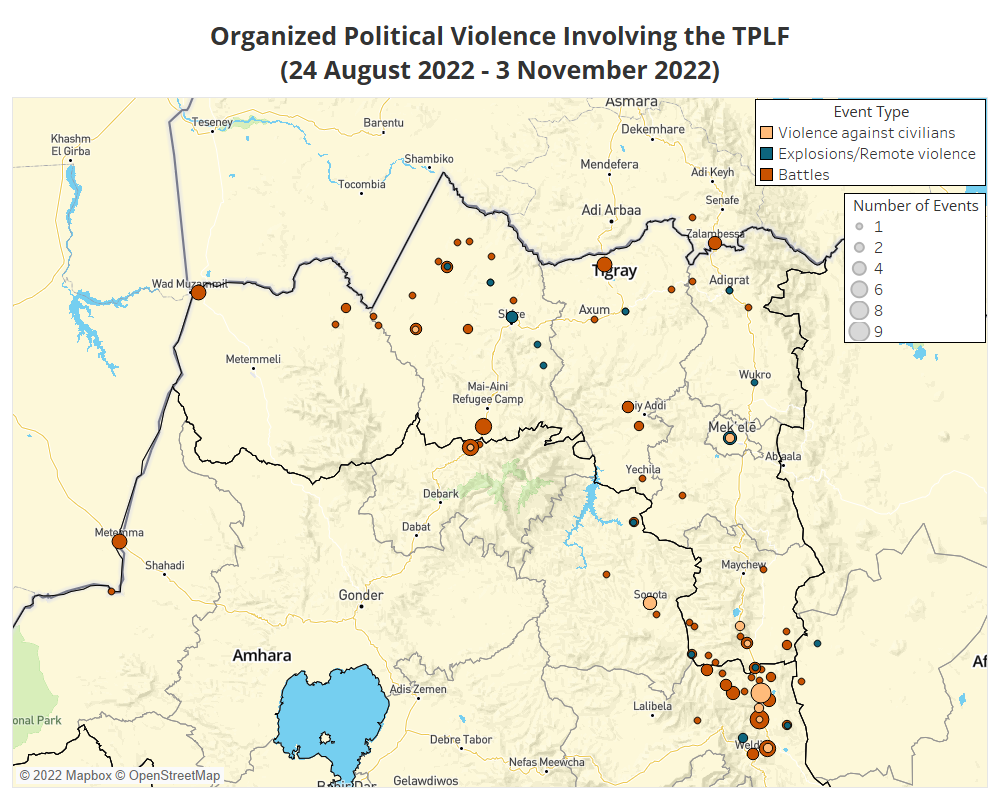

After five months of relative calm, the northern Ethiopia conflict reignited again on 24 August when TPLF forces clashed with the ENDF, Amhara regional special forces, and Fano militias in North Wello zone in Amhara region and Southern Tigray zone in Tigray region. Both sides accused each other of initiating the new round of armed clashes (Twitter @TigrayEAO, 24 August 2022; Twitter @FdreService, 24 August 2022). According to the US Special Envoy for the Horn of Africa, Mike Hammer, there had been signs that the TPLF might initiate another round of violence during his visit to Tigray on 2 August. According to some TPLF leaders, their forces were ready to wage war if the federal government did not restore communications and basic services (Africa Regional Media Hub, 20 September 2022). This round of conflict manifested in organized political violence mostly concentrated in Tigray region, though some events involving the TPLF and its clashes with government forces, Amhara and Fano militias, Eritrean soldiers, and various regional special forces were also recorded in Afar and Amhara regions (see map below).

This led to the fourth stage of the conflict, which lasted until 2 November 2022, when the Ethiopian government and TPLF leaders signed the AU-led Agreement for Lasting Peace through a Permanent Cessation of Hostilities. The TPLF accepted the AU-led peace negotiations with the federal government on 11 September 2022 (Twitter @TigrayEAO, 11 September 2022). In the month leading up to the agreement, pro-government forces – the ENDF, Amhara regional special forces, and Amhara and Fano militias – along with allied troops from Eritrea, made rapid gains, retaking control of dozens of cities, towns, and villages in Tigray and Amhara regions.

The Peace Agreement and Spoilers

The Agreement for Lasting Peace through a Permanent Cessation of Hostilities was signed after more than a week of formal peace talks between the Ethiopian government and TPLF leaders in Pretoria, South Africa. A week before the signing, pro-government forces had the upper hand in the conflict and had regained control of many major towns in the region, including Alamata, Adwa, Aksum, Shire, and Adigrat, closing in on the regional capital, Mekele (AP, 25 October 2022; EMS, 27 October 2022). Before signing the agreement, the parties had three informal meetings led by Mike Hammer – one in Seychelles in March 2022 and two in Djibouti in June 2022 (New York Times, 8 October 2022).

The agreement consists of 15 articles and centers on three main issues. First, the parties agreed to cease hostilities in the region and specified that all TPLF forces would disarm, demobilize, and reintegrate (DDR) within 30 days of signing the agreement (The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ethiopia, 4 November 2022). The parties also agreed to use humanitarian aid exclusively for humanitarian purposes, and the federal government agreed to expedite humanitarian aid into Tigray region. Moreover, both sides committed to restoring constitutional rule in Tigray by declaring the September 2020 election null and void, reinstating the federal government’s authority, and establishing a transitional government in the region. The federal government was also tasked with deploying the ENDF to protect the international borders of Ethiopia.

Despite the agreement specifying that “disarmament of heavy weapons will be done concurrently with the withdrawal of foreign forces from the region,” Eritrean forces have reportedly continued attacks against civilians, including killing an unspecified number of civilians as well as looting shops and vehicles in areas under the forces’ control (Le Monde, 15 November 2022; Reuters, 2 December 2022; Twitter @reda_getachew, 27 November 2022; Twitter @ProfKindeya, 10 November 2022).

Most Ethiopians and members of the international community welcomed the peace agreement. However, some diaspora Tigrayans and Amhara nationalists expressed concern over the agreement’s contents. The diaspora Tigrayans, in particular, voiced concern over the disarmament of TPLF forces and questioned why Eritrea was not mentioned by name in the agreement (Twitter @GlobalGsts, 12 November 2022). Amhara ethno-nationalists also opposed the agreement over the contested Welkait, Tselemti, Tsegede, and Raya areas, arguing that “any arrangement or outcome that doesn’t recognize these lands as Amhara means there will not be lasting peace in the region” (Foreign Policy, 16 November 2022). Some of the contested areas, like Welkait, Tselemti, and Tsegede, have been governed by Amhara regional authorities since the start of the northern conflict. During his briefing to the House of Representatives, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed insisted that the situation in these areas would be resolved in compliance with the rules and regulations of the country (Fana Television, 15 November 2022).

Specifics regarding the withdrawal of foreign troops and non-ENDF forces from Tigray pose a set of potential problems. First, the agreement fails to specify to which border the EDF or Amhara regional special forces must withdraw. On the northern border, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed agreed in June 2018 to accept the 2002 decision of the Eritrea–Ethiopia Boundary Commission, which awarded Badme town to Eritrea, ending the ‘no war, no peace’ period between the two countries (BBC, 5 June 2018). However, the northern conflict erupted before officially handing over Badme to Eritrea. As a result, EDF forces regained control of Badme from Tigray regional forces during the course of the conflict. In the lists of preconditions the TPLF released in July 2021 and February 2022, the group insisted on the withdrawal of non-TPLF forces to their pre-conflict territories, which would imply the TPLF retaking control of Badme town (VOA Amharic, 18 February 2022; BBC, 4 February 2022; BBC Amharic, 19 February 2022; see also EPO Weekly: 3-9 July 2021).

This also poses a challenge to the south and west of the region. Welkait, Humera, and Tsegede areas in Western Tigray zone are currently de facto autonomous areas unofficially governed by Amhara region. Amhara regional forces took control of these areas at the outset of the conflict. Western Tigray zone has been contested for the last 30 years and became part of Tigray region after the implementation of ethno-federalism by the TPLF-led EPRDF – the ruling coalition from 1991 to 2019. Amharas living in these areas sought re-association with Amhara region during that time (Foreign Policy, 28 April 2021; Amhara Media Corporation, 8 July 2021). The TPLF, however, insists that Western Tigray zone should remain part of Tigray region. For residents of Amhara region, Western Tigray has become a nationalist rallying cry; rumors of a possible armed response should the government return the area to the TPLF are common across Amhara (for more, see EPO Weekly: 3-9 July 2021 and EPO Monthly: February 2022).

Further complications have come from factors related to the TPLF Central Committee and the Tigray regional government releasing multiple statements requesting corrections to the the AU-led agreement signed in Pretoria. In these statements, both entities requested that three main issues be corrected in the agreement. First, they stated that the TPLF did not send any representatives to negotiate in South Africa; rather, they were sent by the “Tigray government” (Tigray TV, 12 November 2022; Tigray TV, 13 November 2022). This distinction is significant, as the TPLF wishes to negotiate from the position of a legitimate ruling entity rather than an armed faction. The government of Ethiopia opposes this request and asserts that the TPLF is not a legitimate entity ruling Tigray region, a position it took in 2020 after the TPLF held an election that the federal government declared “illegal” (Reuters, 8 September 2020). As such, the TPLF spokesperson and one of the signatories of the peace agreement, Getachew Reda, indicated that he wanted to negotiate as the representative of the “Tigray government,” but both the AU and “others” were not willing to accept this request (BBC Amharic, 15 November 2022).

The TPLF has maintained throughout the negotiation process that it does not command any armed forces, claiming instead that the Tigray people had created the TDF as a self-defense mechanism out of necessity (Tigray TV, 12 November 2022; Tigray TV, 13 November 2022). The peace agreement clearly relinquishes the TPLF’s ability to retain an armed force independent of the federal government. Members of the TPLF and its supporters have expressed concern that this disarmament could expose them to additional harm by forces from Eritrea or the federal government (BBC, 3 November 2022). One of the challenges for the TPLF is convincing its members and supporters to accept the terms of the peace agreement. The Head of the TPLF forces, General Tadesse Werede, indicated there are political and military forces within the TPLF that do not accept the peace agreement, and that they could represent a hindrance in its implementation. He further stated that as per the declaration signed on 12 November 2022 in Nairobi, Kenya, the commanders have briefed TPLF forces about the peace agreement arrangements, and that the forces have begun to enter selected locations and “their disengagement will follow within the next two to three days” (Tigray TV, 22 November 2022). Tigray TV has since shown TPLF forces leaving some areas like Zeleambesa, Abergele, and Chercher fronts (Tigray TV, 1 December 2022). The commander in chief of the TPLF indicated that the TPLF has “accomplished 65% disengagement” of its forces (Reuters, 4 December 2022). It is, however, unclear whether the disarmament of TPLF forces has begun or not. The Technical Planning Joint Committee, which is comprised of members of the ENDF and TPLF forces, as well as the AU and is mandated to outline the details of the disarmament of TPLF forces, met in Shire town on 30 November 2022 (African Union, 1 December 2022).

Trust is an essential element for the success of a peace agreement. To cultivate trust between the TPLF and the federal government, the AU agreed to establish a Monitoring and Verification Team to oversee and monitor the implementation of the agreement. This team can be considered a third-party guarantee. However, it is unclear how the team will address potential breaches of the agreement. The US government, one of the observers of the South Africa peace talks, stated its willingness to impose sanctions against any spoilers to the peace agreement (Reuters, 15 November 2022). So far, over a month since both parties signed the agreement, the Monitoring and Verification Team has not yet been established. The presence of a third-party team on the ground monitoring the process and providing information to the public would have the advantage of holding both parties accountable to the agreement. Otherwise, there is a chance that misinformation could be disseminated among the opposing sides, which might, in turn, affect the DDR process.

Another challenge is that according to the peace agreements, the federal government is responsible for expediting humanitarian aid to the Tigray region, restoring basic services, and protecting the borders of Ethiopia from any foreign forces. While reports indicate humanitarian aid is being delivered to the region and basic services like electricity are being restored in some areas, no state institutions have yet reported on if members of EDF have withdrawn from the region. Effective institutions are essential in resolving disputes by establishing trust among the conflicting parties. If they are effective, parties can bring their dispute to the established institutions in order to resolve it peacefully as per the rules and regulations of a country. Currently, the government institutions in Ethiopia are weak, and the three branches of the government – the legislative, executive, and judiciary – are not independent. The checks and balances among these bodies are weak (BTI Transformation Index, 2022), as the ruling party controls the legislative bodies and all decisions seem to be cascaded from the top down, i.e. from the top leadership of the Prosperity Party. If there are no effective institutions trusted by all parties, any conflicting party might take up arms to resolve their dispute through force. In a recent interview with BBC HARDtalk, TPLF spokesperson Getachew Reda indicated that if the questions of the Tigray people are not resolved, the disarmament of TDF might not be complete (BBC, 24 November 2022).

Despite these weaknesses in the peace agreement process and an uncertain road ahead, one must also consider the passing window for conflict at this point. The war raged for two years, decimating populations in Tigray, Afar, and Amhara regions. It has been extremely expensive, both in terms of financial resources and manpower. The war has also been costly in terms of popular support, especially in Tigray region, where people have endured large-scale destruction, starvation, and displacement as a result (The Guardian, 23 March 2022). The likelihood of the conflict reigniting is largely related to whether or not the elements of the TPLF could both mobilize and justify another round of conflict. There are indications – including the loss of large amounts of territory shortly before the agreement – that this likely will not transpire. As pointed out by a senior Africa analyst, “the Tigrayan leaders made huge concessions” (BBC, 3 November 2022) and they are unlikely to resume armed conflict without giving peace an opportunity.

As noted earlier, two critical elements identified by scholars – third-party guarantees and effective institutions – that facilitate sustainable peace after a peace agreement are so far absent in the Ethiopian context. In addition, various spoilers surround and threaten to affect the agreement, including the Tigrayan diaspora, disarmament issues, the Western Tigray zone tensions, and the non-withdrawal of the EDF.

Given the costs of restarting the conflict, however, there is a chance that this peace agreement will succeed. Complications to the peace process mean there are risks that the TPLF – or TPLF splinter factions – could resume insurgent activity. It is increasingly vital to establish a third-party guarantee like the Monitoring and Verification Team, track the progress of implementing the peace agreement on the ground, and hold both parties accountable to the agreement in order to foster sustainable peace in the region.