EPO Monthly Update | April 2024

Abiy Ahmed’s Sixth Year

April at a Glance

Vital Trends

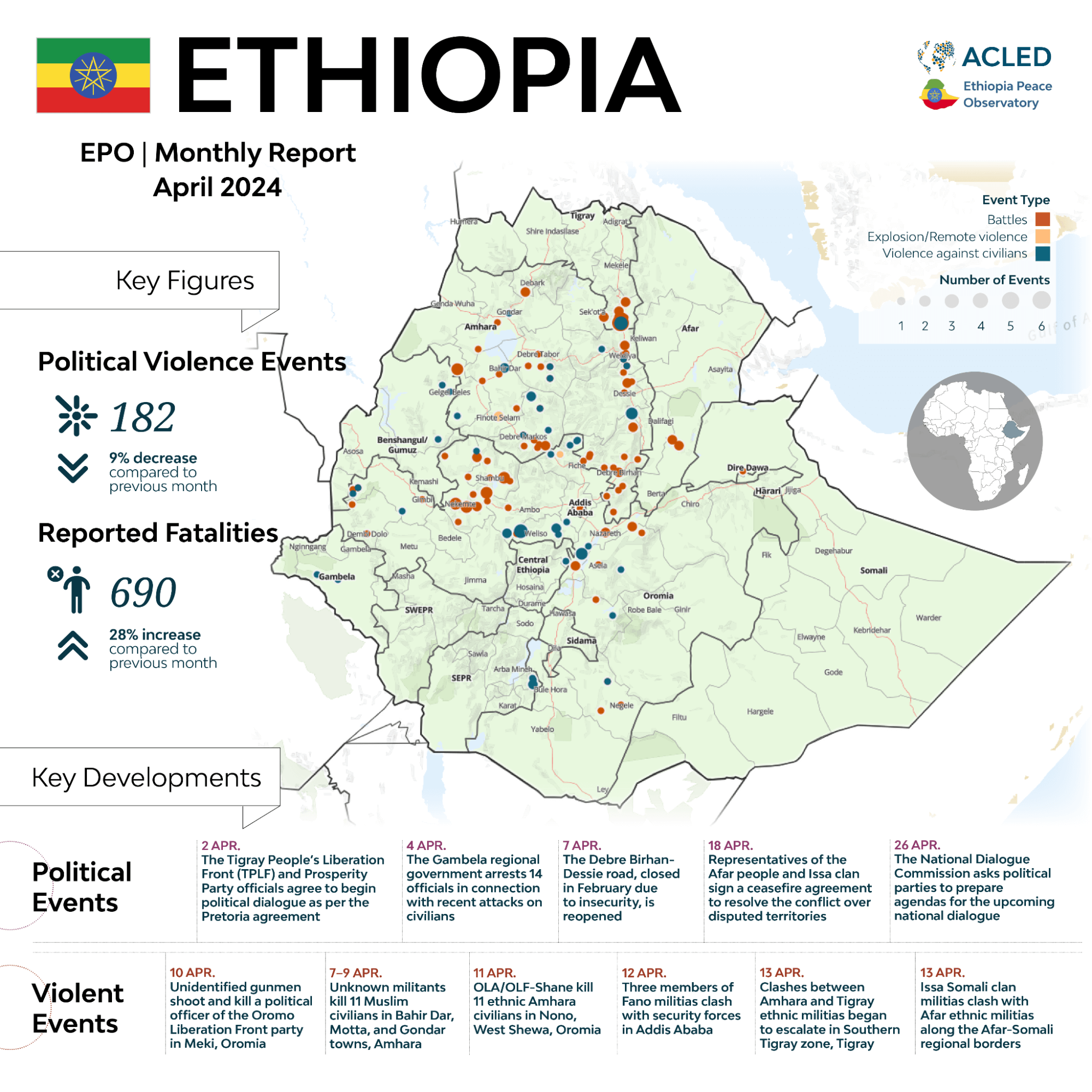

- In April, ACLED records 182 political violence events and 690 reported fatalities in Ethiopia.

- Battles and violence against civilians were the two most common event types in April, with 123 and 56 events, respectively. Most of these events were linked with ongoing conflict between government forces and insurgencies in Amhara and Oromia regions.

- ACLED records the most political violence in April — 72 events and 247 reported fatalities — in Oromia region. ACLED records 70 events and 314 reported fatalities in the Amhara region in April, of which the majority — 278 reported fatalities — were linked to battles between Fano militias and the government security forces.

Abiy Ahmed’s Sixth Year

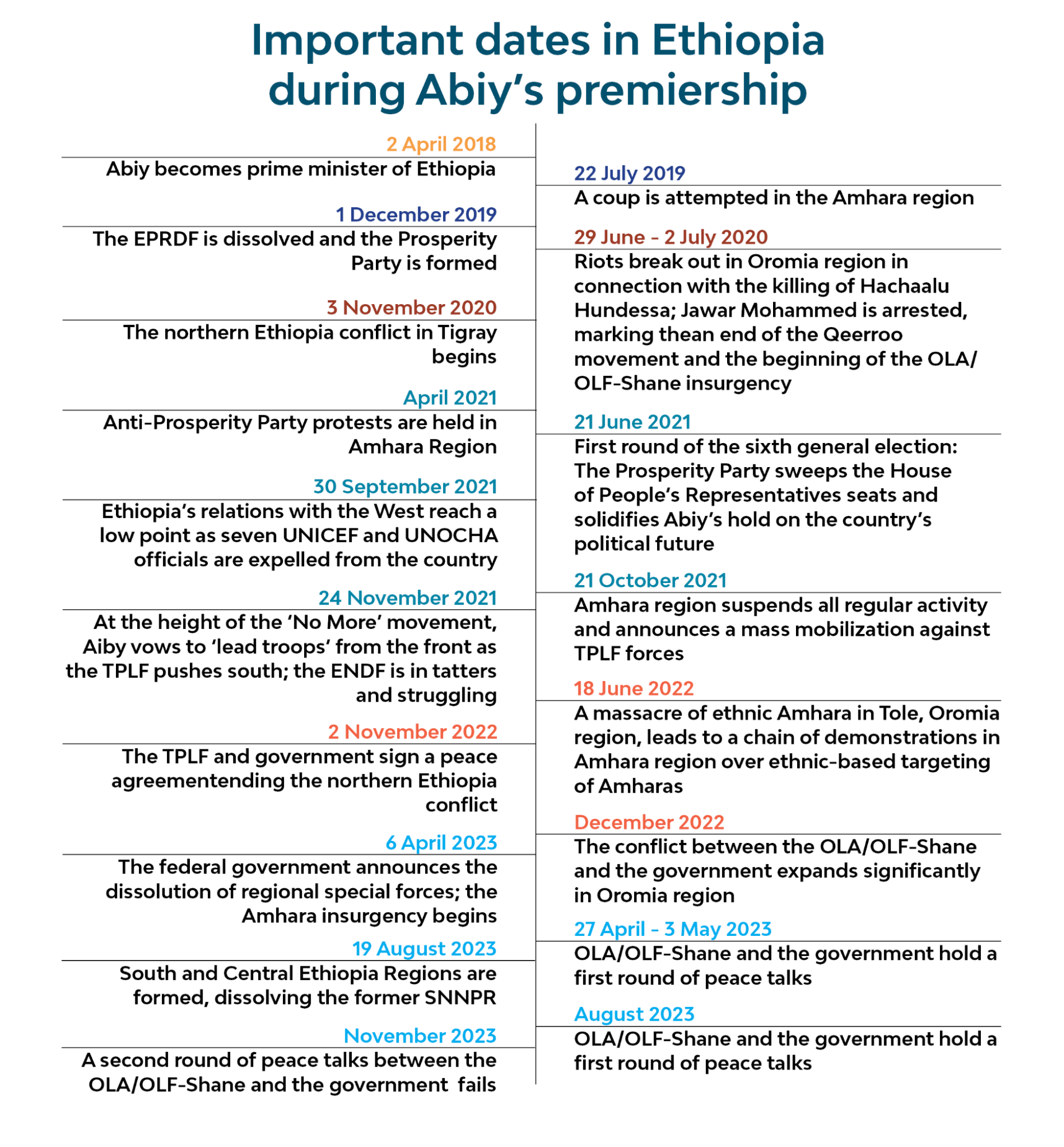

In April 2024, Abiy Ahmed finished his sixth year as prime minister of Ethiopia, ruling over one of the most violent political periods the country has experienced in its modern political history. Following the resignation of Hailemariam Desalegn in February 2018 during the height of mass demonstrations in Oromia and Amhara regions, Abiy was elected prime minister by Ethiopia’s parliament. Since that time, Abiy has managed to keep Ethiopia intact, and he remains at the helm of a country that has been buffeted by a series of crises, including major conflicts, multiple concurrent active insurgencies, and ethnic strife. While dealing with these crises, Abiy has not demonstrated a clear transitional framework with concrete steps for the country’s future relationship with ethnic federalism, resulting in rapid alignment and misalignment with various factions. This period is notable for Abiy’s heavy-handed approach toward political opponents and for turbulent and violent political instability. In order to remain prime minister and keep Ethiopia from disintegration, Abiy has been forced to reposition himself against former allies so as to benefit from conflict, no matter how deep the damage. Ethiopia’s most recent clashes in contested territories between Amhara and Tigray regions, which escalated in April, are a prime example of the consequences of the transactional leadership patterns Abiy has developed since taking office.

Alignment Changes and Ethnic-Based Federalism

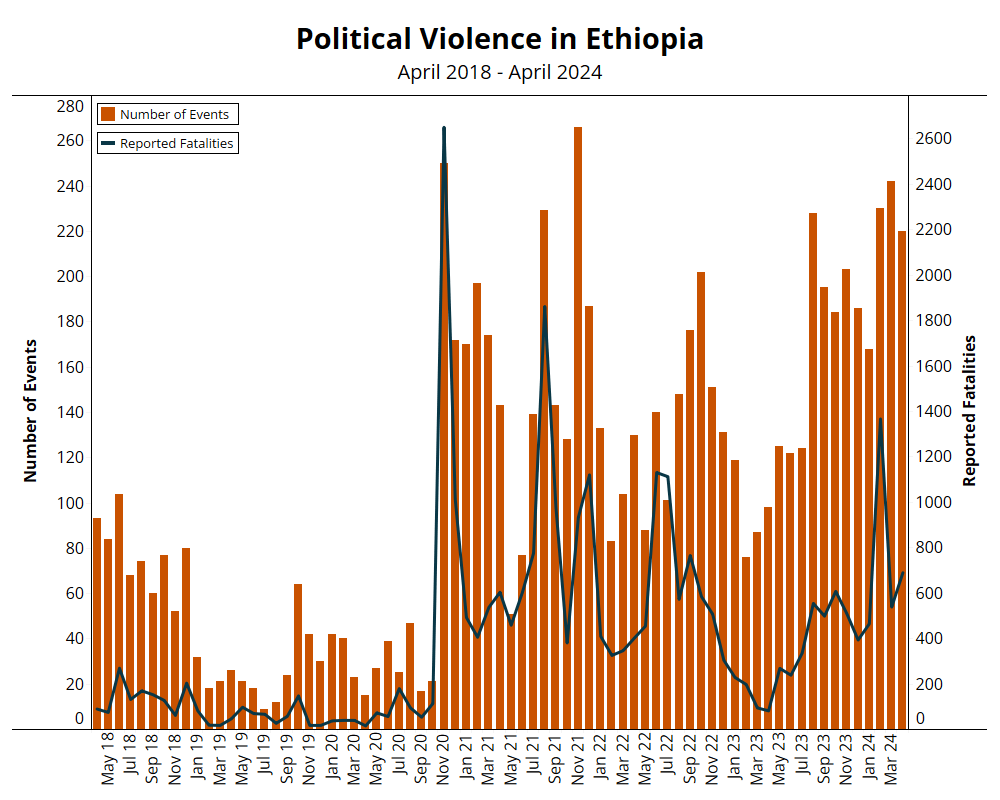

Since 2018, Abiy’s leadership has been characterized by varying degrees of political violence (see graph below), much of it connected to the debate over ethnic federalism in Ethiopia’s constitution — and the government’s changing political alliances in this debate. Ethnic federalism is a system of power distribution that claims to protect Ethiopia’s ethnic groups from repression by granting them a guarantee of political autonomy and protected ethnic identity.1Marcus, H. G. and Crummey, Donald Edward, ‘History of Ethiopia. Encyclopedia Britannica,’ 19 March 2024 In contrast, Abiy’s political ideology — ‘Medemer’ — focuses on a united Ethiopia and shared vision for the future that maintains respect for group identities.2Abiy Ahmed, ‘Medemer,’ 21 October 2019 Abiy was catapulted to his position by two ethno-nationalist youth movements — namely Qeerroo-led demonstrations in Oromia region and the Fano youth movement in Amhara region — and was hailed by both as a hero who would reform a repressive regime then dominated by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), which led Ethiopia from 1991 to 2018.

Despite his power base among allies in ethno-federalist youth movements, Abiy moved the country in a different direction. In 2019, Abiy dissolved the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front3Tom Gardner, ‘Will Abiy Ahmed’s Bet on Ethiopia’s Political Future Pay Off?,’ 21 January 2020 (EPRDF) coalition party and created the Prosperity Party — a merger of ethnic-based parties.4The Prosperity party was created when the Amhara Democratic Party (ADP), the Oromo Democratic Party (ODP), and the Southern Ethiopian People’s Democratic Movement (SEPDM) dissolved to join the Prosperity Party. Other parties that dissolved and merged with Prosperity Party are the Afar National Democratic Party (ANDP), the Benshangul-Gumuz People’s Democratic Unity Front (BGPDUF), the Ethiopian Somali People’s Democratic Party (ESPDP), the Gambella People’s Democratic Movement (GPDM), and the Harari National League (HNL). As Abiy began to implement the new party, disagreements among other top politicians emerged.5Brook Abdu, ‘Ruling party suspends Lemma from leadership,’ The Reporter, 15 August 2020 Demonstrations and riots were reported throughout Oromia region, sparked by the rumored arrest of a popular opposition figure, Jawar Mohammed, in October 2019 and later the assassination of Hachalu Hundessa, a popular Oromo musician, in June 2020. Heavy-handed reactions by the government, including thousands of arrests,6Amnesty International, ‘Ethiopia: Fears grow for thousands arrested after killing of Oromo singer,’ 18 July 2020 squashed protests. By the end of 2019, Oromo youth who were once supporters of Abiy flocked to the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) — referred to by the government as the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF)-Shane — and the anti-government insurgency demanding political autonomy for ethnic Oromo swelled in Oromia region. Sustained violence involving the OLA/OLF-Shane increased significantly in 2020 and 2021. ACLED data show that the militant group has been involved in 997 clashes, resulting in an estimated 5,881 reported fatalities since the end of 2019. While the government has managed to keep the OLA/OLF-Shane from controlling any major cities in Oromia region, its influence in rural areas has led to widespread insecurity and economic difficulties. Peace negotiations involving the government and OLA/OLF-Shane leadership failed in May and November 2023, and Oromia region remains volatile.

A similar cycle was observed in Amhara region, where demonstrations by the Fano youth movement contributed to the overthrow of the former TPLF-led government and brought Abiy Ahmed into power. In contrast to the Qeerroo youth movement in Oromia, who advocate for autonomy for ethnic Oromo, the Fano in Amhara region are deeply connected to, and advocate for, both a united Ethiopia and the restoration of Amhara governance over what they consider to be traditional Amhara homelands.7Fano and other Amhara ethno-nationalist organizations advocate for the Amhara administration of lands such as Metekel zone in Benshangul/Gumuz region and areas of Western and Southern Tigray zones in Tigray region based on the population’s connection to Amhara culture and language. To the Fano, while Abiy’s leadership was preferable to that of the TPLF-led EPRDF government, and they may have agreed initially with the ideals of ending ethnic federalism in theory, they view the Prosperity Party as Oromo-dominated and exclusive of Amhara interests. Ethnic violence targeting Amhara civilians in Oromia, Benshangul/Gumuz, and other locations in the country during Abiy’s leadership has led to accusations that the government could not, or would not, protect Amhara people, many of whom live outside Amhara region. Anti-government demonstrations swelled in Amhara region in the spring of 2021 during bouts of violence in Ataye town, Oromia special zone, in Amhara region. Disagreements about the national direction and ethnic Amhara interests were put on hold during the northern Ethiopia conflict while the federal government fought alongside Fano militias8Fano militias are armed Fano youth, many of whom participated in the Fano youth movement in urban areas, but the term also includes rural-based Fano militias that are traditionally organized at the community level. against the TPLF forces. However, these disputes quickly resurfaced just before the end of the northern conflict in November 2022. As it had in Oromia region, the government turned on its former allies and attempted to disarm the militias and quiet Amhara ethno-nationalist figures using heavy-handed tactics like arrests. In turn, the Fano insurgency rose in 2023.

In Tigray region, the TPLF opposed and refused to join the new ruling party, the Prosperity Party, citing differences in political ideology. Instead, Tigrayan members of the federal government abandoned their posts and headed to Tigray. In September 2020, they held a regional election in defiance of the federal government, which had decided to postpone the sixth general election for one year due to the COVID-19 pandemic.9Al Jazeera, ‘Speaker of Ethiopia’s upper house resigns after polls postponed,’ 9 June 2020; Giulia Paravicini, ‘Ethiopia’s Tigray holds regional election in defiance of federal government,’ Reuters, 8 September 2020 Political grievances were expressed violently for the first time on 3 November 2020, when the Tigray regional special forces and militias, under the direction of the TPLF, attacked the northern command of the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) in Tigray region. The conflict expanded to the neighboring regions until the day before it entered a second year, 2 November 2022, when the federal government and the TPLF signed the Agreement for Lasting Peace through a Permanent Cessation of Hostilities in Pretoria.

Throughout the regions of Ethiopia’s periphery, the creation of the Prosperity Party meant that areas politically excluded under the EPRDF’s rule were given new opportunities in the federal government, and violence levels in these areas eventually, and especially in 2024, fell to all-time lows.

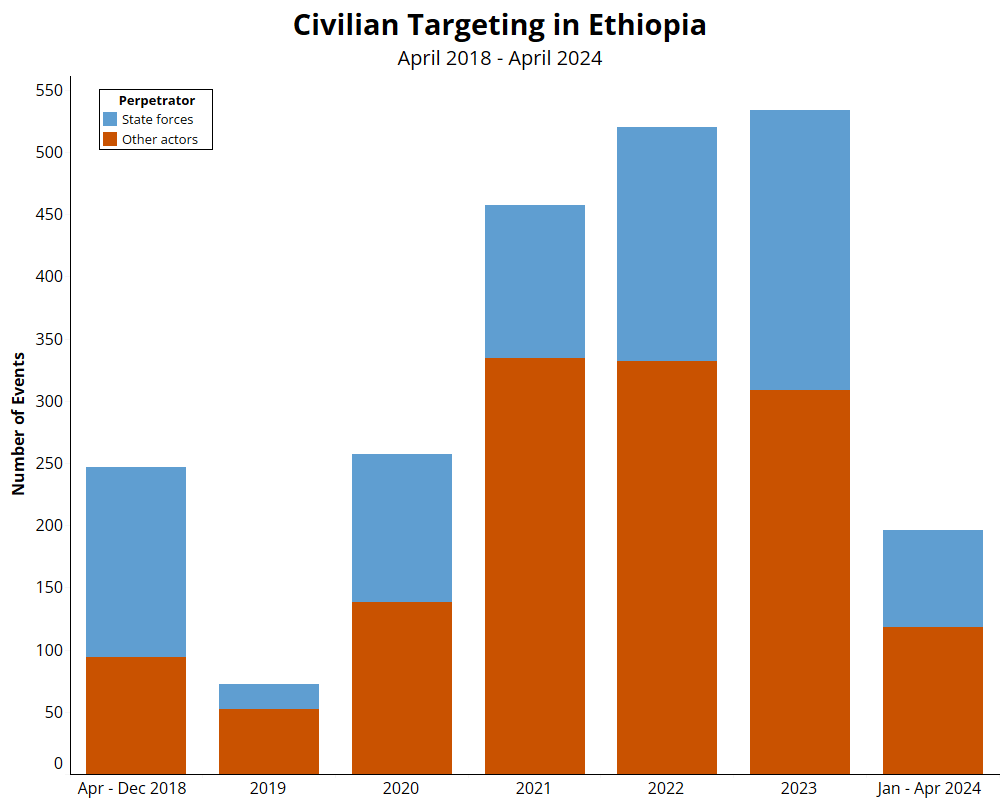

Violence in Abiy’s Ethiopia

Abiy has demonstrated his willingness to use violence to protect the federal government, the party, and his own position. State-sponsored violence against civilians has been a prevalent feature of his government. Government forces are responsible for 40% of all civilian targeting incidents since 2018 (see graph below), resulting in an estimated 3,583 reported fatalities, though that estimate is likely low.

The federal government under Abiy has made some efforts toward achieving peace — like engaging in peace talks with armed groups, establishing disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) programs for former fighters, and funding wider opportunities for finding political solutions, including the National Dialogue — but it has been unable to do so sustainably. Though the Pretoria agreement stopped the conflict in the north, recent clashes between Tigray and Amhara region forces in Southern and Western Tigray zones demonstrate that the agreement may only be temporary. Talks between the federal government and the OLA/OLF-Shane failed twice, with violence increasing in Oromia as a result. The government has hinged a lot on the upcoming national dialogue, designed to bring the country’s populations back into some common political understanding, but the process has been slow, and critical stakeholders, like the Oromo Liberation Front party, may not participate, as they claim the process is dominated and handcrafted by the government.10Sisay Sahilu, ‘The historical responsibility of the National Dialogue Commission and the concerns behind its implementation, The Reporter, 5 May 2024 Wazema Radio, ‘Attempts to reconcile the 13 political parties that defected from the national dialogue platform have so far failed,’ 27 March 2023; Seyum Getu, Shewaye Legesse, and Azeb Tadesse, ‘The opinion of politicians on the proposed national dialogue,’ DW Amharic, 10 February 2022

In Ethiopia today, neither the government nor the anti-government groups have demonstrated a willingness to allow Ethiopians to negotiate major political issues without violence. As conflict wears on, it risks becoming self-reproducing, and demobilization and disarmament become more difficult.

Abiy’s Seventh Year

As Abiy moves into his seventh year as prime minister, he faces two main insurgencies: the Fano militias in Amhara region and OLA/OLF-Shane in Oromia region. In both regions, federal troops are in control of most major roadways and towns. Neither insurgency could realistically threaten the federal government, Addis Ababa, or even regional capitals. They are, however, symptoms of deeper political issues in the country that are unlikely to go away and will continue to worsen as time goes on. Ethiopia under Abiy is not a place where political differences can be negotiated without risk of violence whether it is his fault or the fault of those who oppose him.

A key factor in the next year of Abiy’s premiership will be the federal government’s security resources, including the ENDF and the federal police. The ENDF went through a series of major reforms during the northern Ethiopia conflict, including an increase in recruitment, expansion of drone and airstrike capabilities, and a reshuffling of top officials.11Ethiopia Insight, ‘Oromia’s Bale is facing a multi-layered crisis,’ 23 November 2022; Fana Broadcasting, ’A meeting with General Ababew,’ 21 January 2022; France24, ‘Ethiopia’s Abiy replaces army chief as casualties mount in Tigray conflict,’ 8 November 2020 These reforms will undoubtedly be put to the test as the ENDF is Abiy’s most important tool in addressing violence — be it anti-government insurgency or other security problems.

The most serious challenge Abiy faces as he moves into his seventh year is the issue of contested territory in Southern and Western Tigray zones in Tigray. Clashes between Tigray and Amhara militias in Southern Tigray zone began in February and escalated in April, threatening the 2022 Pretoria peace agreement. While clashes have been limited in scale, the issues involved will test Abiy’s ability to lead a response that will preserve the peace accord and facilitate a political settlement that discourages the future use of violence.

Abiy is in a tight bind, caught between two critical pieces of the country. On one hand, the TPLF has been weakened considerably but still commands a significant number of armed fighters.12VOA Amharic, ‘Getachew Reda: There is still mistrust between the federal government and the Tigray region,’ 13 February 2024 It also still wields influence among international actors, a fact that was weaponized heavily during the northern conflict and remains a factor today. Abiy can ill afford to allow a second conflict to erupt in Tigray region; the federal government needs to appear as if it is making an effort to uphold its end of the Pretoria agreement and keep Tigray intact and relatively stable. On the other hand, militias under the command of leadership placed by the Amhara Prosperity Party — a vital ally to Abiy — control Western and Southern Tigray zones and will not allow them to be retaken by Tigray region without a major conflict. These militias are currently aligned with the federal government and have gone so far as to allow ENDF units to attack Fano positions from the territory they control. This is a fragile alliance at best, and any indication that the federal government could allow the TPLF-led interim regional government of Tigray to retake Western and Southern Tigray zone would spark a new conflict that could engulf northern Ethiopia once again — something Abiy clearly wishes to avoid. At the moment, small, localized conflicts can benefit Abiy as they weaken two of his political enemies — Fano and the TPLF — simultaneously. Should conflict expand and involve wider elements from both sides, it risks becoming another costly war that disrupts economic opportunities and adds to displacement.

Thus far, the ENDF has managed to stop the conflict in Southern Tigray zone before it escalates into more widespread fighting. However, clashes are likely to resume and intensify and could require additional security measures. The federal government has indicated that it would like to be the only armed force in control of the contested areas, and that issues of disputed territories would be solved via a referendum.13VOA Amharic, ‘The federal government issued a warning about the conflict in the Raya Alamata area,’ 19 April 2024; BBC Amharic, ‘The administration in the disputed areas of Amhara and Tigray will be dissolved – the Minister of Defense,’ 23 March 2024 Whether it is able to follow through remains to be seen.