EPO Monthly Update | March 2024

Violence Patterns in Ethiopia’s Periphery

March at a Glance

Vital Trends

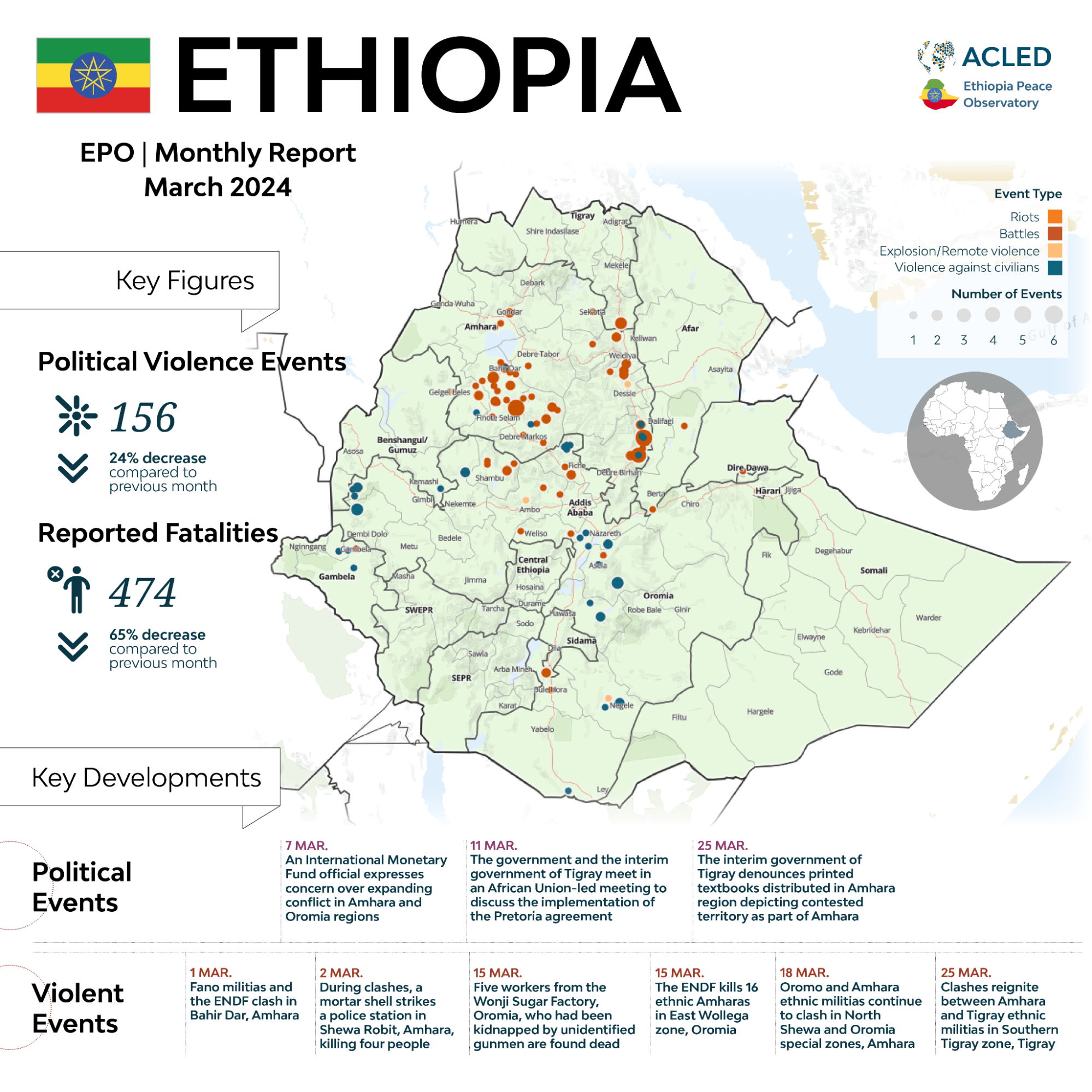

- In March, ACLED records 156 political violence events and 474 reported fatalities in Ethiopia.

- Battles and violence against civilians were the two most common event types in March, with 110 and 41 events, respectively.

- ACLED records the most political violence in March — 80 events and 234 reported fatalities — in Amhara region. Clashes between Fano militia and government forces, which have been fighting since August 2023, accounted for 70% of the events in the region.

Key Developments

Violence Patterns in Ethiopia’s Periphery

Since 2018, Ethiopia has been beset by a myriad of conflicts fought at the local, regional, and national levels. At center stage in Ethiopia are large conflicts, fought primarily over issues revolving around the country’s political core of Amhara, Oromo, and Tigray. These conflicts reflected a shifting balance at the core — namely, an ascent of the Oromo elite at the perceived expense of the Tigray and Amhara cores. The northern Ethiopia conflict between November 2020 to November 2022 was fought primarily in Tigray, Afar, and Amhara regions and removed Tigray region from its previous position in the country’s political arena.

The Oromo Liberation Army/Oromo Liberation Front-Shane (OLA/OLF-Shane) insurgency in Oromia region is an internal power struggle involving many Oromo elites. The newest Fano insurgency, fought in Amhara region, is a direct rejection of the new Oromo elite and its allies embodied by the ruling Amhara Prosperity Party in Ethiopia’s top political ranks. While these larger conflicts occurring at Ethiopia’s center dwarf the country’s smaller conflicts in terms of geographical scale and number of reported fatalities, violence patterns in Ethiopia’s periphery states are an important metric in understanding the overall stability of the country’s core. The ebbs and flows of these smaller conflicts in far-flung parts of the country are often indicative of larger political shifts happening at a national level. Falling levels of political violence in periphery areas, as is happening in the first quarter of 2024, could indicate a stabilized core and a stronger central regime that has solidified its relationship with the periphery.

Peace in Ethiopia’s Prosperous Periphery

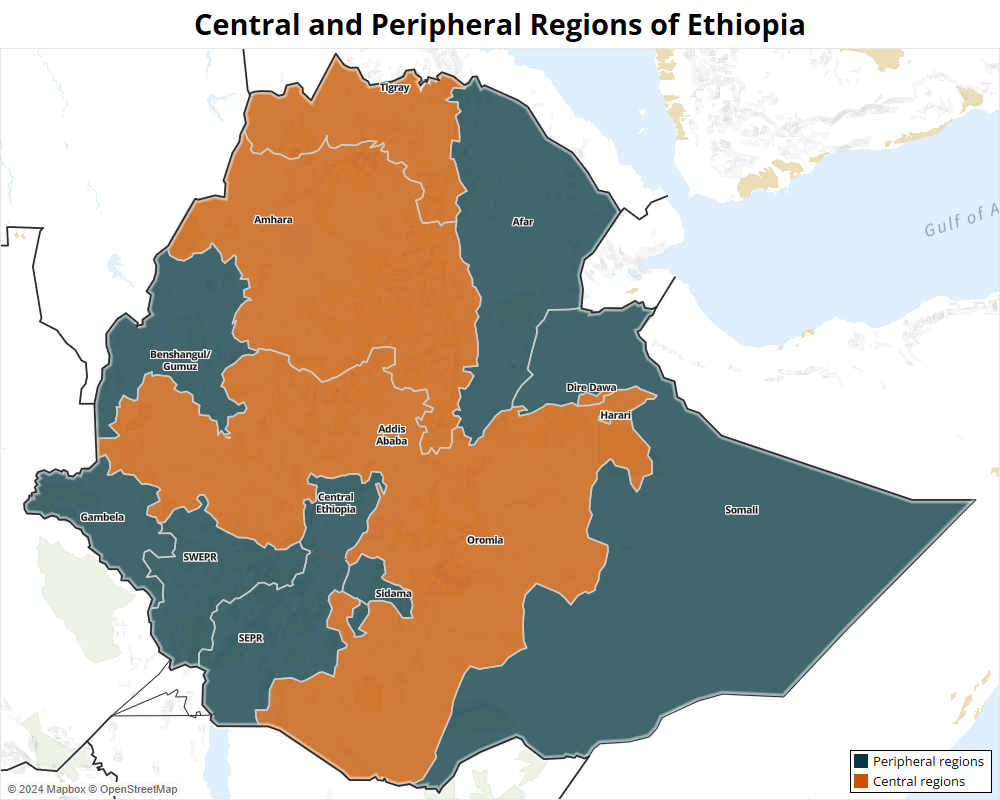

The relationship between Ethiopia’s periphery and center is a topic that has been discussed by political scholars over the years, with many defining Ethiopia’s political center as the ‘highland core’ versus a ‘lowland periphery.’1Christopher Clapham, ‘Centralization and Local Response in Southern Ethiopia,’ African Affairs Vol. 74, No. 294, January 1975 Periphery locations in Ethiopia’s modern political sphere can be defined loosely in the non-Oromo south regions (South Ethiopia, South West Ethiopia, Sidama, and Central Ethiopia regions); Afar and Somali regions in the east; and Gambela and Benshangul/Gumuz regions in the west.

Peace in periphery regions is important to the federal government, especially as the resource-rich areas of Oromia2Addis Standard, ‘Analysis: Conflict Brews: Coffee growers in Western Oromia battle for beans amidst violence, instability,’ 15 March 2024 and Amhara3VOA, ‘Due to the conflict, the Amhara region, where sufficient taxes were not collected, caused further crisis,’ 31 October 2024 regions and the industry centers of Tigray region4Selamawit Mengesha, ‘Ministry assesses war-affected industries in Tigray,’ The Reporter, 21 January 2023 have been hit so hard by conflict. Periphery areas hold infrastructure and resources crucial for foreign export, which provides the government with foreign currency.5International Trade Administration, ‘Ethiopia – Country Commercial Guide,’ 18 January 2024; Samuel Bogale, ‘Poor export performance aggravates forex stress,’ The Reporter, 11 March 2023 Examples include sugar plantations in the south, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam in Benshangul/Gumuz region, and critical roadways in Afar region linking Ethiopia to the Red Sea via Djibouti. Somali region provides a critical buffer zone between Ethiopia and Somalia and related al-Shabaab activity.

Between 2019 and 2023, political violence affecting over 2 million people was observed at high rates in Ethiopia’s periphery regions. The Konso and Segen area peoples zones have been the scene of intense bouts of ethnic-based violence over administration borders. The disputed territories between Somali and Afar regions led to hundreds of reported fatalities and thousands of displacements. Metekel zone in Benshangul/Gumuz region was one of the most violent locations in the country between 2020 and 2022. Communal violence was commonplace in Bench Sheko zone. Later, in the fall of 2022, demands for administrative autonomy were raised in Gurage zone, leading to violence and stay-at-home protests. Notably, both Somali and Gambela regions were relatively peaceful between 2018 and 2024 compared to their respective violent pasts.

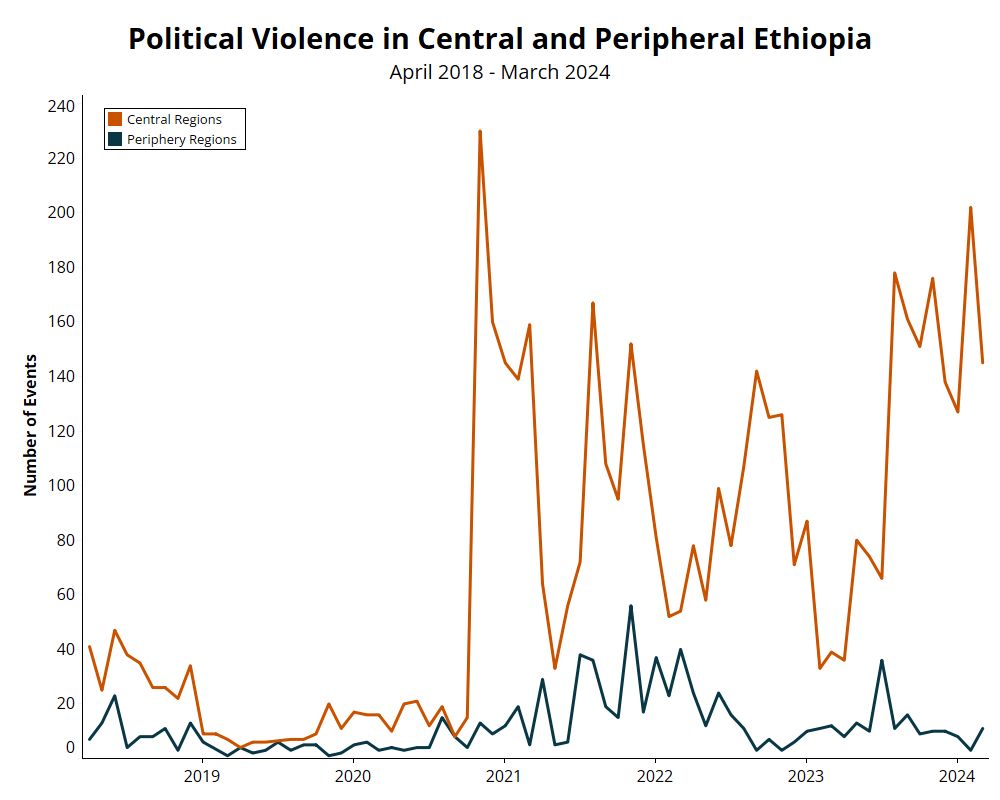

Violence in these periphery regions reached a peak in 2021, slowing in 2022 and 2023 (see graph below). Thus far in 2024, Ethiopia’s periphery continued the trend of low rates of political violence,6ACLED does not track criminal violence, which has been on the rise throughout the country and in peripheral areas. See: BBC Amharic, ‘It was stated that more than five thousand suspects were arrested in Addis Ababa,’ 1 February 2024 the inverse of the sustained high amounts of violence in Oromia and Amhara regions. In past years, those involved in peripheral-area political violence have usually included groups advocating for autonomy under the ethno-federalist system or ownership of land based on ethnic demographics. In 2018, when Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed first came to power, some ethnic-based claims for autonomy were given consideration as specified under Ethiopian law. Moreover, the creation of the Prosperity Party in December 2019 officially ended the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front era, bringing periphery regions into a new position of political opportunity.7Yohannes Gedamu, ‘Why Abiy Ahmed’s Prosperity Party is good news for Ethiopia,’ Al Jazeera 18 December 2019; Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation, ‘The change is that the Afar people who have been excluded from the politics of the center of the country where they now receive appropriate representation: Afar State Government Communication Service,’ 3 April 2024 In turn, seismic shifts occurring at the country’s center reopened conflict over the control of resources in the periphery areas.8Jonah Wedekind, ‘Prosperity to the Periphery,’ Rift Valley Institute, 27 March 2024 By 2022, the country was dealing with high levels of violence in periphery areas and a pandora’s box of over 30 self-administration and identity-related requests submitted by local authorities.

A Center Grip

In 2023, Abiy’s Prosperity Party made several critical moves to gain greater control over the administration of these peripheries and rein in violence. The government’s decision to disband the regional special forces in April 2023, some of whom were later integrated into the Ethiopian National Defence Force (ENDF) and federal police forces, gave it greater power over the regional states to enact decisions made about security in the regions at the federal level. In addition to hard power in the form of military intervention, a number of political maneuvers were used to gain leverage for the federal government.

In the former Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples region, the government implemented a unique solution of breaking up the larger region, denying direct requests for autonomy by grouping them together into four new regions that could be dealt with on a smaller scale. The move paid off and resulted in a reduction of autonomy requests — largely due to ethnic elites being placed into Prosperity Party positions in the newly formed regions — and a coinciding drop in violence. Local leadership in the newly created regions and woredas became useful allies to the federal government — extremely limited outside their own political spheres but powerful locally in areas that contain critical resources.9Hyun Jin Choi and Clionadh Raleigh,‘The geography of regime support and political violence,’ Democratization, 26 April 2023

Other political maneuvers — notably the federal government’s arrest of the former Somali regional president and appointment of Mustafa Mohamed Omar in 201810Ashenafi Endale, ‘Walking the line between politics, Principles,’ The Reporter, 6 November 2024 — were made elsewhere. In Benshangul/Gumuz region, the federal government relied heavily on the ENDF and command posts, as well as a number of local peace processes, deploying strategies like offering political appointments to former members of rebel groups, among other incentives including land ownership, to bring peace to the region.

Outside of appointment and reorganization, federal authorities have reversed their position on autonomy requests. For example, in the case of Gurage zone, warning that it “will not tolerate illegal and irregular activities under the guise of the restructuring requests” and arresting people accused of supporting the self-administration request of Gurage zone.11Addis Standard, ‘News: SNNP Council submits zonal, special woredas restructuring to House of Federation; Bu’i city in Gurage zone establishes command post,’ 5 August 2022 Similar crackdowns have occurred in Arba Minch.

Moving Forward

If violence was a key feature in the periphery of Abiy Ahmed’s early years, peace in the same locations in the first few months of 2024 demonstrates that the federal government has achieved a significant goal. Political control of Ethiopia’s periphery through a central Prosperity Party, and all the resource benefits that entails, marks a major milestone. While conflict rages in Amhara and Oromia regions at the country’s center, control of the periphery puts significant resources into the federal government’s hands and may enable it to better tackle the rest of the country’s ongoing problems. The coming months will tell if the peace achieved in the first part of 2024 is sustainable.